The British Society for the History of Science

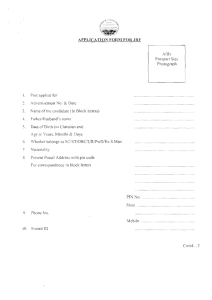

advertisement