Caribbean History From Colonialism to Independence AM217 David Lambert

advertisement

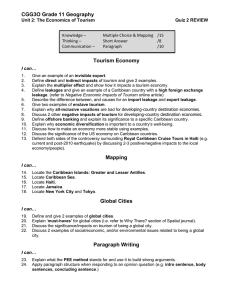

Caribbean History From Colonialism to Independence AM217 David Lambert Lecture: The growth of tourism Tuesday 1st March, 11am-12pm The growth of tourism 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The origins of Caribbean tourism Tourism in Cuba and Jamaica Modern Caribbean tourism Theorising Caribbean tourism Tourist imagery The world’s biggest industry • In 1994, tourism became the world’s biggest industry (overtaking petroleum and motor vehicles) • By 2014, tourism accounted for almost 10% of global GDP and 9% of employment • Tourism is ‘a force that arises from, and gives rise to, geographical unevenness and social inequality’ (Mullins, 2004, p. 97) • Tourism is one of the Caribbean region’s only ‘comparative advantages’ in the globalising, neo-liberal world Tourism in the Caribbean • Tourism accounts for 14% of the GDP of the Caribbean and 11.3% of employment (60% in the Bahamas and Antigua, less than 10% in Trinidad and Tobago) • Number-one earner of foreign currency • Region receives only 2.4% of world’s tourists (25 million visitors in 2012) • 50% come from USA and 25% from Europe Caribbean tourism The [tourist] industry hinges on the exploitation of a number of the region’s resources, particularly sun, sea and sand, but also on its tropical rainforests and coral reefs as well as its music, such as reggae and calypso, its cuisine, and other cultural symbols such as carnival. It offers a variety of packages, including golf vacations, weddings and honeymoons, dive trips, and eco-tours, its sole raison d’être to provide pleasure to the visitor…Male and female labor (sic) and energies constitute a part of the package that is paid for and consumed by the tourist during the period in which she or he seeks to relax and enjoy – in the leisure time the tourist has set aside to recuperate and restore the mind and body in order to maintain a healthy and productive working life on returning home… K. Kempadoo, Sun, sex, and gold (1999), pp 20-21. The origins of Caribbean tourism • First hotel built in region in 1778 (in Nevis) • Throughout much of its history, the Caribbean was a notoriously unhealthy region for visitors due to malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever etc. • Elite leisured travellers began to visit the region in the mid-to-late 19th century for health reasons • They travelled on new trans-Atlantic steamships to ‘winter in the West Indies’ Royal Mail Steam Packet Company Royal Mail Steam Packet Company The origins of Caribbean tourism • First hotel built in region in 1778 (in Nevis) • Throughout much of its history, the Caribbean was a notoriously unhealthy region for visitors due to malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever etc. • Elite leisured travellers began to visit the region in the mid-to-late 19th century for health reasons • They travelled on new trans-Atlantic steamships to ‘winter in the West Indies’ • Hotels were built to serve visitors (e.g. Royal Victorian Hotel in the Bahamas opened in 1861) Hotels Hotels The origins of Caribbean tourism • First hotel built in region in 1778 (in Nevis) • Throughout much of its history, the Caribbean was a notoriously unhealthy region for visitors due to malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever etc. • Elite leisured travellers began to visit the region in the mid-to-late 19th century for health reasons • They travelled on new trans-Atlantic steamships to ‘winter in the West Indies’ • Hotels were built to serve visitors (e.g. Royal Victorian Hotel in the Bahamas opened in 1861) • Larger-scale tourism developed first in Cuba Tourism in Cuba • Tourism developed in Cuba in the early twentieth century in the context of the increasing US military presence. • Sex tourism was the seedy side of Havana’s club culture and the city came to be known as the commercial sex capital of the western hemisphere Tourism in Cuba • Tourism expanded in Cuba following US occupation (which saw large-scale mosquito eradication and improvements in local sanitation) • Great War encouraged Americans to visit Cuba • Prohibition in 1920s • Tourism became Cuba’s third largest source of foreign currency (after sugar and tobacco) Visitor numbers to Cuba 400,000 350,000 300,000 250,000 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 0 1914 1924 1934 1944 1954 Tourism in Cuba • Tourism expanded in Cuba following US occupation (which saw large-scale mosquito eradication and improvements in local sanitation) • Great War encouraged Americans to visit Cuba • Prohibition in 1920s • Tourism became Cuba’s third largest source of foreign currency (after sugar and tobacco) • Tourism virtually disappeared after 1959, which created opportunities elsewhere in the Caribbean • Tourism enabled again after 1989 (2.5m in 2005 and 50% foreign exchange earnings) Tourism in Jamaica • Initial development in 1880s linked to growth of banana trade (although there was already a steamship service) Tourism in Jamaica • Initial development in 1880s linked to growth of banana trade (although there was already a steamship service) • Titchfield Hotel constructed at Port Antonio in early 1900s Hotels Tourism in Jamaica • Initial development in 1880s linked to growth of banana trade (although there was already a steamship service) • Titchfield Hotel constructed at Port Antonio in early 1900s • Tourist development in Jamaica was marked by patterns that were later repeated across the region: – Support of government – Capital for investment came from outside – Fiscal incentives provided to foreign investors Modern Caribbean tourism • From the 1960s, ‘mass tourism’ began to develop across the region, which reflected: – Efforts by newly independent states sought to diversify their economies – Growth of international jet travel • Many Caribbean governments provided incentives to promote external investment and attract hotel companies, tour operators and airlines. One consequence was that tourism was soon dominated by foreign interests. • The mass tourism was not suited to the social realities of the Caribbean, providing only seasonal employment and few opportunities for career development. • The requirements of hospitality did not sit easily in newly-independent societies in which black nationalism remained significant. Tensions between tourism and nationalism THE LIFE YOU WISH YOU LED The villas come equipped with gentle people named Ivy or Maud or Malcolm who will cook, tend, mend and launder for you. Who will ‘Mister Peter, please’ you all day long, pamper you with homemade coconut pie…weep when you leave. Quoted in B. Mullins, ‘Caribbean tourism’ (2004), p. 102. Caribbean cruises • There has been a rapid expansion of the cruise ship industry, e.g. Antigua (pop. of 91,295) had 522,342 cruise passenger arrivals in 2014. • Caribbean reduced to a picturesque backdrop. • Day-trippers contribute little to local economies. • Environmental problems of ship waste disposal. All-inclusive hotels • ‘Cash-free’ vacation dominated by companies such as Sandals and Superclubs. • Today, ‘the all-inclusive concept has come to symbolise the Caribbean tourism experience’ (Mullins, 2004, 107). • A solution to tourist fears of crime and harassment. Private beaches ‘Friendly natives’ Mustique: The ultimate all-inclusive • Mustique, a dependency of St. Vincent was bought by a foreign company, Mustique Company Ltd in 1968. • It is now a ‘secret hideaway’ of the rich and famous. All-inclusive hotels • ‘Cash-free’ vacation dominated by companies such as Sandals and Superclubs. • Today, ‘the all-inclusive concept has come to symbolise the Caribbean tourism experience’ (Mullins, 2004, 107). • A solution to tourist fears of crime and harassment. • Problems: – Benefits to local economies is even more limited than that of other hotels. – Privatisation of beaches. – Fuels local antagonism. Theorising Caribbean tourism • ‘Plantation tourism landscape’ model (based on Antigua): ‘Plantation tourism landscape’ model Theorising Caribbean tourism • ‘Plantation tourism landscape’ model (based on Antigua): 1. Pre-tourism (1632-1949) – agriculture dominant 2. Transition (1950-1969) 3. Tourism dominant (1970 to present) • Emphasis on continuity, not change. Tourism and the plantation system [S]imilarities include the dominant role of expatriate investment capital as well as ownership and management, the seasonal nature of employment, the need for a large component of unskilled local labour, the reliance upon a narrow range of markets, and the responsiveness of each activity to external rather than local needs. David Weaver, ‘The evolution of a “plantation” tourism landscape’ (1988), p. 320. Theorising Caribbean tourism • ‘Plantation tourism landscape’ model (based on Antigua): 1. Pre-tourism (1632-1949) – agriculture dominant 2. Transition (1950-1969) 3. Tourism dominant (1970 to present) • • Emphasis on continuity, not change. Such critical assessments of tourism often draw on dependency theory. Selling the image of the Caribbean The natural tropical island environment with some of the world’s most beautiful beaches is an idyllic setting for a vacation, and so tourism has become a significant industry in the Caribbean. T. Boswell (2003), in Hillman and D’Agostino (eds) Understanding the contemporary Caribbean, p. 47. BUT, there is nothing ‘natural’ about such desires – they have a history to them. An idyllic setting for a vacation ‘America’ (c. 1600): Paradise on earth Edenism and hedonism Caribbean tourism is vested in the branding and marketing of Paradise…[S]uch imagery picks up longstanding visual and literary themes in European representations of Caribbean landscapes as microcosms of earthly paradise – including the temptation and corruption that go along with being in new Edens. These discursive formations of Caribbean scenery are closely related to the emergence of ‘hedonism’ as a key set of practices associated with Caribbean tourism. Depictions of Caribbean ‘Edenism’…underwrite performances of touristic ‘hedonism’ by naturalising the region’s landscape and its inhabitants as avatars of primitivism, luxuriant corruption, sensual stimulation, ease and availability. M. Sheller, ‘Natural hedonism’ (2004), p. 23. Tourist imagery • Contemporary tourist discourse is embedded in a long history of Western ideas about the Caribbean. Elements include: – Oldest notions of the region as a luxuriant paradise. – Ideas of the Caribbean as available (for intervention and pleasure). ‘America’ (c. 1600): Paradise on earth Tourist imagery • Contemporary tourist discourse is embedded in a long history of Western ideas about the Caribbean. Elements include: – Oldest notions of the region as a luxuriant paradise. – Ideas of the Caribbean as available (for intervention and pleasure). – After the abolition of slavery, the Caribbean became reinscribed as a natural landscape (rather than a productive, developed landscape). This reflected its declining economic importance and the continuing influence of Romanticism (a cultural shift in European thought that valued wild and untamed landscapes). Pre-abolition: The Caribbean represented as a productive, developed landscape Tourist imagery • Contemporary tourist discourse is embedded in a long history of Western ideas about the Caribbean. Elements include: – Oldest notions of the region as a luxuriant paradise. – Ideas of the Caribbean as available (for intervention and pleasure). – After the abolition of slavery, the Caribbean became reinscribed as a natural landscape (rather than a productive, developed landscape). This reflected its declining economic importance and the continuing influence of Romanticism (a cultural shift in European thought that valued wild and untamed landscapes). Tourist imagery • Contemporary tourist discourse is embedded in a long history of Western ideas about the Caribbean. Elements include: – Oldest notions of the region as a luxuriant paradise. – Ideas of the Caribbean as available (for intervention and pleasure). – After the abolition of slavery, the Caribbean became reinscribed as a natural landscape (rather than a productive, developed landscape). This reflected its declining economic importance and the continuing influence of Romanticism (a cultural shift in European thought that valued wild and untamed landscapes). • Mimi Sheller (2004) describes this discourse as ‘Edenism’. Edenism and hedonism Caribbean tourism is vested in the branding and marketing of Paradise…[S]uch imagery picks up longstanding visual and literary themes in European representations of Caribbean landscapes as microcosms of earthly paradise – including the temptation and corruption that go along with being in new Edens. These discursive formations of Caribbean scenery are closely related to the emergence of ‘hedonism’ as a key set of practices associated with Caribbean tourism. Depictions of Caribbean ‘Edenism’…underwrite performances of touristic ‘hedonism’ by naturalising the region’s landscape and its inhabitants as avatars of primitivism, luxuriant corruption, sensual stimulation, ease and availability. M. Sheller, ‘Natural hedonism’ (2004), p. 23.