Caribbean History From Colonialism to Independence AM217 David Lambert

advertisement

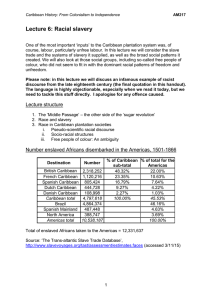

Caribbean History From Colonialism to Independence AM217 David Lambert Lecture: Racial Slavery Tuesday 17th November, 11am-12pm Racial Slavery 1. The ‘Middle Passage’ – the other side of the ‘sugar revolution’ 2. Race and slavery 3. Race in Caribbean plantation societies i. Pseudo-scientific racial discourse ii. Socio-racial structures iii. Free people of colour: An ambiguity Enslaved Africans disembarked in the Americas, 1501-1866 Destination Number British Caribbean 2,318,252 French Caribbean 1,120,216 Spanish Caribbean 805,424 Dutch Caribbean 444,728 Danish Caribbean 108,998 Caribbean sub-total 4,797,618 Brazil 4,864,374 Spanish Mainland 487,488 North America 388,747 The Americas - total 10,538,227 % of Caribbean sub-total % of total for the Americas 48.32% 23.35% 16.79% 9.27% 2.27% 100.00% 22.00% 10.63% 7.64% 4.22% 1.03% 45.53% 46.16% 4.63% 3.69% 100.00% Total of enslaved Africans taken to the Americas = 12,331,637 Enslaved Africans disembarked in the Americas, 1501-1866 Spanish Mainland 5% Brazil 46% North America 4% Caribbean 45% Enslaved Africans disembarked in the Caribbean, 1501-1866 Danish Caribbean 2% Dutch Caribbean 9% Spanish Caribbean 17% French Caribbean 24% British Caribbean 48% Enslaved Africans disembarked in British Caribbean, 1501-1866 Montserrat/Nevis Trinidad/Tobago 2% 2% British Guiana St. Vincent 3% 2% Dominica 5% Grenada 6% Other British Caribbean 3% Jamaica 44% St. Kitts 6% Antigua 6% Barbados 21% Enslaved Africans disembarked in French Caribbean, 1501-1866 French Guiana Guadeloupe 3% 7% French Caribbean unspecified 2% Martinique 19% Saint-Domingue 69% Volume and direction of the transAtlantic slave trade Volume and direction of the transAtlantic slave trade Volume and direction of the transAtlantic slave trade Slave imports, 1501-1866 450000 400000 350000 300000 250000 200000 150000 100000 50000 0 Barbados Jamaica Martinique Saint-Domingue Cuba Puerto Rico High plantation death rates Deaths exceeded births on the West Indian plantations from the sixteenth century on, and the slave trade supplied the deficit. The migration of the slaves was not, therefore, a one-time event. The plantations needed a continuous supply of a new labour, if only to remain the same size. P. Curtin, The rise and fall of the plantation complex (1990) Defining race • A political and social construction, rather than an biological fact. • A marker of human difference based on physical criteria (skin colour, nose shape, type of hair). • Classifications based on physical criteria are entangled with value judgements about social status and moral worth. • Closely associated with colonialism and imperialism. • The body is a key site in racial discourse. Race and the body [T]he definitive and insidious feature of racism [is]…its grounding in the human body and in lineage, which thus defines it as inescapable, a non-negotiable attribute that predicts socio-political power or lack of power. This idea has a relatively recent history…It was not until the eighteenth century that race took on a consistently judgmental connotation, indicating differences among peoples meant to describe superiority and inferiority and implying an inheritance of status that was inescapable. J. Chaplin, ‘Race’ (2002), p. 155. Another product of the circum-Atlantic world [R]acism in its present form is a specific product of Atlantic history. J. Chaplin, ‘Race’ (2002), p. 155. The psycho-cultural argument In the writings of several of the church fathers of western Christendom…the colour black began to acquire negative connotations, as the colour of sin and darkness…The symbolism of light and darkness was probably derived from astrology, alchemy, Gnosticism and forms of Manichaeism; in itself it had nothing to do with skin colour, but in the course of time it did acquire that connotation. Black became the colour of the devil and demons. Jan Pieterse, White on black (1992), p. 24. Negative connotations of blackness in the European imagination The socio-economic argument Slavery in the Caribbean has been too narrowly identified with the Negro. A racial twist has thereby been given to what is basically an economic phenomenon. Slavery was not born of racism: rather racism was the consequence of slavery. Unfree labor in the New World was brown, white, black, and yellow; Catholic, Protestant and pagan…Here, then, is the origin of Negro slavery. The reason was economic, not racial; it had to do not with the color of the laborer, but the cheapness of the labor…The features of the man…his ‘subhuman’ characteristics so widely pleaded, were only the later rationalizations to justify a simple economic fact: the colonies needed labor… Eric Williams, Capitalism and slavery (1944), pp 7, 19, 20. African slaves as cheap labour Race and slavery • Blackness did have negative cultural associations in premodern Europe (the psycho-cultural argument). • Nevertheless, demands for labour were colour blind during the initial stages of the colonisation of the Caribbean, e.g. white indentured labourers (the socioeconomic argument). • Crucially, as more plantation labour was supplied by enslaved Africans, then being a ‘slave’ and being ‘black’ became intertwined. Race and slavery The practices of slavery Ideas about race Practices of slavery and ideas of race •The whip was the ultimate emblem of slavery and its use a sign of racial ideas about black embodiment. Race and slavery • Blackness did have negative cultural associations in premodern Europe (the psycho-cultural argument). • Nevertheless, demands for labour were colour blind during the initial stages of the colonisation of the Caribbean, e.g. white indentured labourers (the socioeconomic argument). • Crucially, as more plantation labour was supplied by enslaved Africans, then being a ‘slave’ and being ‘black’ became intertwined. • In addition, the meaning of blackness changed during the eighteenth century from the external manifestation of an internal paganism to becoming itself a source of symbolic degradation. • Hence, religious notions of difference are joined by and later replaced by truly racial ideas of ‘natural’ black inferiority focused on the body. Pseudo-scientific racial discourse The Negro’s faculties of smell are truly bestial, nor less their commerce with the other sexes; in these acts they are libidinous and shameless as monkeys, or baboons. The equally hot temperament of their women has given probability to the charge of their admitting these animals frequently to their embrace. An example of this intercourse once happened, I think, in England. Ludicrous as it may seem I do not think that an orang-utan husband would be any dishonour to an Hottentot female [a woman from southern Africa]. [The orang-utan] has in form a much nearer resemblance to the Negro race than the latter bear to white men. Edward Long, The history of Jamaica (1774). Barbados Slave Code (1661) • Codified earlier less formal provisions • Established that enslaved people were to be treated as chattel property • Denied them basic rights under Common Law • Granted slaveowners great powers • Served as the basis for the slave codes adopted in other English colonies: e.g. Jamaica (1664), South Carolina (1696) and Antigua (1702) French Code Noir (1685) • Slaves had to be baptized • Specified quantities of food and clothes to be given to slaves • Enslaved husbands and wives (and prepubescent children) were not to be sold separately • A slave who struck their master, his wife, mistress or children would be executed • Masters could chain and beat slaves but may not torture nor mutilate them • Masters who killed their slaves would be punished Punishment Populations in the late century th 18 100% 90% 80% 70% Freedpeople 60% Slaves 50% 40% Whites 30% 20% 10% 0% Puerto Rico Cuba Martinique St Domingue Jamaica Barbados The socio-racial structure of Jamaica 100% 90% 80% 70% White 60% 50% Freedpeople 40% Enslaved 30% 20% 10% 0% 1750 1830 The socio-racial structure of a Caribbean plantation society, c. 1830 Whites Free people of colour Slaves Free people of colour: An ambiguous group The free coloured population • Inter-racial sex was a common feature of Caribbean societies and most ‘mixed-race’ people remained in slavery • But, during the eighteenth century, a free non-white population became increasingly significant • This initially emerged due to the manumission of enslaved people by their white owners: – For favoured servants – For their children – For informing on conspirators • In addition, as some slaves bought their freedom and it was passed from mother to child, the free coloured population began to increase naturally The socio-racial structure of a Caribbean plantation society, c. 1830 Whites Free people of colour Slaves Complex racial classifications in early nineteenth century Jamaica Free people of colour: A troubling presence There is…a third description of people of whom I am more suspicious of evil than either the whites or slaves: these are the Black and Coloured people who are not slaves, and yet whom I cannot bring myself to call free. Letter from the governor of Barbados, 6 June 1802 Free coloureds and the hospitality sector Free coloureds in the urban Caribbean Restrictions on free people of colour • There were limits to their freedom, no matter how ‘white’, across the Caribbean (e.g. they could not vote, hold public office, serve on juries or give evidence against whites) • Many aspects of daily life were also segregated • Resentment particular acute in French Caribbean as restrictions contradicted the Code Noir • Some free coloureds appealed against legal disadvantages and won personal privileges (e.g. Jamaica, 1733) • As the wealth and size of the free coloured population grew, new legislative restrictions were introduced (e.g. Jamaica, 1761) Troubling figures: Poor whites Seminar this week: ‘Everyday slavery’ 3pm and 4pm in H3.03 (as usual)