Lecture 3: European ‘discovery’

advertisement

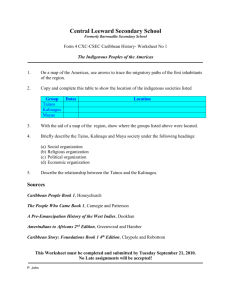

Caribbean History: From Colonialism to Independence AM217 Lecture 3: European ‘discovery’ This lecture will focus on the initial European encounter with the Caribbean, connecting this to the ‘expansion of Europe’. It will also draw attention to indigenous resistance to conquest. Lecture structure 1. Early globalisation 2. Remembering 1492 and all that 3. The ‘Age of Discovery’ i. The expansion of Europe ii. The beginning of world dominance: The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) iii. An encounter with indigenous peoples iv. The ‘Columbian exchange’ 4. Case study: The colonisation of Hispaniola Globalisation in the Caribbean For Caribbean people all the talk today about the uniqueness of the present era of globalisation is cause to chuckle. They know their histories, and realise they have been through many earlier rounds of globalisation…Historically, the Caribbean is perhaps the most globalised world region. Since the 1500s it has been controlled by outside powers, based economically on imported labour, cleared to create monocultural landscapes of sugar cane, bananas or other crops, and reliant on the import of virtually everything else needed to sustain local populations. R. Potter et al., ‘Globalisation and the Caribbean’ (2004), p. 388. 1492: ‘Discovery’ or ‘Invasion’? While in the context of European history the events associated with Europe’s expansion across the Atlantic are studied under the rubric of ‘exploration’, ‘discovery’, etc., in the context of New World history those same facts can be studied only as invasions and conquests…The quest for gold…drove the Atlantic enterprise throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries…There was nothing either mystical or malign in the search for precious metals. They were the basis of the monetary system of the time, strategic goods without which the new states could not function or compete. The means used in obtaining precious metals was another thing, and no example is earlier or more graphic than the invasion of the islands of the Antilles and the sacking of their gold…What brought the Antilles and, in the long run, all of the New World into association with Europe was the existence of its mineral wealth. The rest was an afterthought. If Columbus had not found signs of gold during his first voyage, his name would never have gone down in history, and the process of uniting the planet would have been postponed. J. Sued-Badillo, ‘The indigenous societies at the time of Conquest’ (2003), p. 275. 1 Caribbean History: From Colonialism to Independence AM217 The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) [The Treaty] is a landmark of great psychological and political importance: Europeans, who by then had not even gone round the globe, had decided to divide between themselves all its undiscovered and unappropriated lands and peoples. The potential implications were vast…The conquest of the high seas was the first and greatest of all the triumphs over natural forces which were to lead to domination by western civilisation of the whole globe. Knowledge is power, and the knowledge won by the first systematic explorers…had opened the way to the age of western world hegemony. Roberts, 1985, quoted in S. Hall, ‘The west and the rest’ (1992), p. 285. The ‘Columbian exchange’ With the arrival of the conquistadores came other more visible elements of their biota, such as cultivated plants and domesticated animals, fruits of the Old World’s Neolithic agricultural revolutions (Crosby 1977, 1986). The 17 ships of Columbus’s second voyage not only brought Spanish subjects to occupy the new territories (as well as pathogenic viruses), but also carried plants and animals that formed an 2 Caribbean History: From Colonialism to Independence AM217 indissoluble part of the Spaniard’s subsistence and farming culture. The former included seeds of wheat, garbanzo [chickpeas], onion, radish, melons, grapes, some unidentified vegetables and fruits (including citrus), and sugarcane; the latter horses, cattle (adult and calves), pigs, sheep, and goats. Reinaldo Funes Monzote, ‘The Columbian Moment’ (2011), p. 91. From encounter to exploitation [In 1503], shipments of gold began to be sent uninterruptedly to Spain, and these shipments continued for more than half a century. And in that year, too, the policy was instituted for enslaving ‘cannibals’; that is, of taking indigenes as slaves to Hispaniola as a labour option…Finally, on 20 December of that fateful 1503, Queen Isabella instituted the practice of encomiendas, the legalization of servile labour. If we take 1494, the first year of the Conquest, as our starting-point, we would have to recognize that it took only nine years to transform the relations between Europeans and indigenes into relations of slavery and exploitation. The worst thing about it was, of course, that Hispaniola became the model for relations throughout the New World. J. Sued-Badillo, ‘The indigenous societies at the time of Conquest’ (2003), p. 276. The colonisation of Hispaniola The indigenous population of the island knew it by various names, including Hayti (meaning ‘mountainous’). At the time of the arrival of the Europeans, the island was roughly divided into divided into at least 4 or 5 chiefdoms, each ruled by a powerful cacique (pronounced ‘ka-seek’). 3 Caribbean History: From Colonialism to Independence AM217 Chronology of the colonisation of Hispaniola 1492 – Columbus landed at what he termed ‘La isla española’ (Hispaniola for short) and established settlement at Navidad 1493 – Returned to find settlement destroyed. Founded Isabela 1500 – 200,000 pesos of gold were sent to Spain, the largest shipment ever 1503 – continuous shipments of gold began and indigenous slaves brought from nearby islands 1506 – first experiments with growing of sugar cane 1518 – import of enslaved Africans permitted 1520 – mines depleted and indigenous population largely destroyed Later the western part of Hispaniola came to be known as Santo Domingo. Estimated indigenous population of Hispaniola (1491-1550) 1200000 1000000 1,000,000 800000 600000 400000 200000 60,000 30,000 11,000 150 1508 1514 1519 1550 0 1491 Indigenous resistance to the Conquest There were several kinds of resistance and reaction to the Conquest. We should make clear that behaviour was not uniform throughout the archipelago because there was not uniformity before the Conquest. On all the islands there were those who considered alliance, or at least compliance with the invaders’ orders, the best option in their particular situation…Yet resistance, too, began almost immediately…[T]je forst important event of a warlike nature was the defeat of the Spaniards in the fort at Navidad, possibly in mid-1493. There were 39 Spaniards killed as a consequence of their crude pursuit and treatment of indigenous women and grudges among themselves… J. Sued-Badillo, ‘The indigenous societies at the time of Conquest’ (2003), p. 280. 4