WHO Handbook Guideline Development

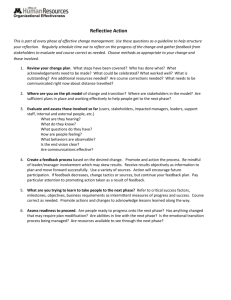

advertisement