Document 12947279

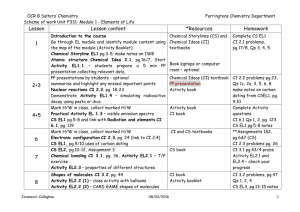

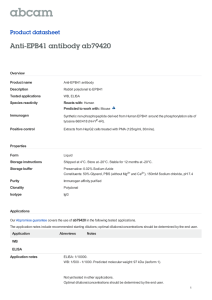

advertisement