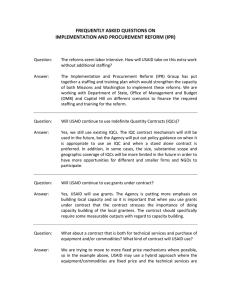

MOVING FORWARD USAID and

advertisement