Slaving Away: Migrant Labor Exploitation and

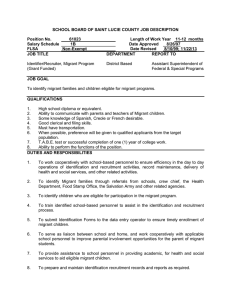

advertisement