W , C P

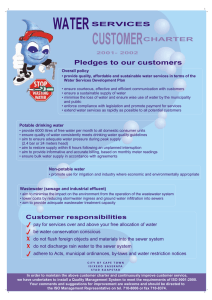

advertisement