Document 12947235

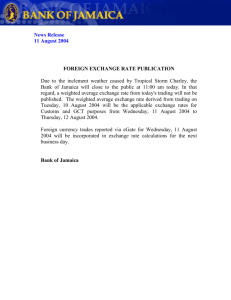

advertisement