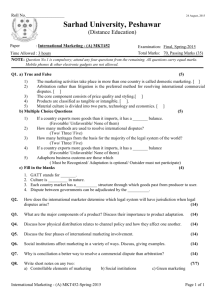

D i s p u t e r... i n t h e

advertisement