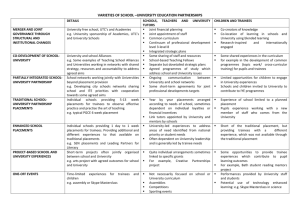

New models of teacher education: collaborative paired placements

advertisement