THE COHEN INTERVIEWS SYBIL CLEMENT BROWN

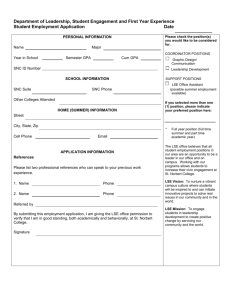

advertisement