. THE COHEN INTERVIEWS MOLLY BREE

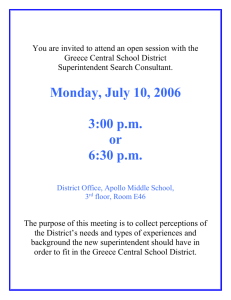

advertisement