Settlement Planning for North Norfolk

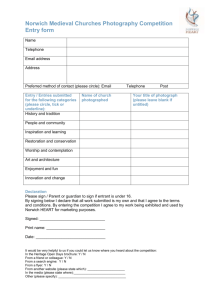

advertisement