DATA RECONCILIATION AND INSTRUMENTATION UPGRADE. OVERVIEW AND CHALLENGES

advertisement

DATA RECONCILIATION

AND INSTRUMENTATION

UPGRADE. OVERVIEW AND

CHALLENGES

FOCAPO 2003.

January 12-15, 2003

Miguel Bagajewicz

University of Oklahoma

OUTLINE

• A LARGE NUMBER OF PEOPLE FROM ACADEMIA

AND INDUSTRY HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO THE AREA

OF DATA RECONCILIATION.

• HUNDREDS OF ARTICLES AND THREE BOOKS HAVE

BEEN WRITTEN.

• MORE THAN 5 COMMERCIAL SOFTWARE EXIST.

• ALTHOUGH A LITTLE YOUNGER, THE AREA OF

INSTRUMENATION UPGRADE IS EQUALLY MATURE

• ONE BOOK HAS BEEN WRITTEN

OUTLINE

• OBSERVABILITY AND REDUNDANCY

• DIFFERENT TYPES OF DATA RECONCILIATION

- Steady State vs. Dynamic

- Linear vs. Nonlinear

• GROSS ERRORS

- Biased instrumentation, model mismatch and outliers

- Detection, identification and size estimation

• INSTRUMENTATION UPGRADE

• SOME EXISTING CHALLENGES

• INDUSTRIAL PRACTICE

Simple Process Model of Mass

Conservation

f2

U1

f4

f1

f8

f6

f3

U2

f5

f1 - f2 - f3 = 0

f2 - f4 = 0

f3 - f5 = 0

f4 + f5 - f6 = 0

f6 - f7 =0

f7 - f8 - f9 = 0

f8 - f10 = 0

f9 - f11 = 0

U3

U4

f10

f7

f9

U5

f11

Material Balance Equations

Variable Classification

f2

U1

f4

f1

f8

f6

f3

U2

U3

f5

U4

f10

f7

f9

U5

f11

Measured (M)

Variables

Observable (O)

Unmeasured (UM)

Unobservable (UO)

Variable Classification

f2

U1

f4

f1

f8

f6

f3

U2

U3

f5

U4

f10

f7

f9

U5

f11

Redundant (R)

Measured (M)

Non-redundant (NR)

Variables

Observable (O)

Unmeasured (UM)

Unobservable (UO)

Conflict among Redundant

Variables

f2

U1

f4

f1

f8

f6

f3

U2

f5

f1 - f7 =0

f1 – f8 – f11= 0

U3

U4

f10

f7

f9

U5

f11

Material Balance Equations

Conflict Resolution

~

~

Min [ f R − f R+ ] T QR−1 [ f R − f R+ ]

Data reconciliation in

s.t.

its simplest form

~

ER fR = 0

Analytical Solution

[

(

~

f R = I − Q R E RT E R Q R E RT

)

−1

]

E R f R+

Precision of Estimates

If z = Γx, and the variance of x is Q, then the variance

~

of z is given by: Q = ΓQΓ T

[

(

~

f R = I − QR ERT ER QR ERT

)

−1

]

ER f

~

+

f NR = f NR

~

~

~

f O = CRO f R + C NRO f NR

+

R

(

~

QR , F = QR , F − QR , F C RT C R QR , F C RT

~

QNR , F = QNR , F

~

Q R

~

T

QO = [C RO C SRO ]

[C RO C SRO ]

Q NR

)

−1

C R QR , F

Some Practical Difficulties

• Variance-Covariance matrix is not Known

• Process plants have a usually a large number of Tanks

• Plants are not usually at Steady State

• How many measurements is enough?

Estimation of the VarianceCovariance Matrix.

•Direct Approach

•Indirect Approach

Almasy and Mah (1984),

Darouach et al., (1989) and

Keller et al (1992)

1 n ~

f R , i = n ∑ f R ,i k

k =1

~

~

1 n ~

Cov ~

−

f R ,i , f R , j =

f

f

∑

R ,i k

R ,i f R , j k − f R , j

n − 1 k =1

(

E R f R+ = r

)

(

)(

Cov ( r ) = E R QR E RT

1) Obtain r

2) Maximum likelihood estimate QR

However, this procedure is not good if outliers are present.

Robust estimators have been proposed (Chen et al, 1997)

)

Tank Hold Up Measurements

Level at t=t0

Level at t=t1

Pseudo-Stream

Steady State formulations are used

The procedure is based on the following

assumptions:

~

~

Min [ f R − f R+ ] T QR−1 [ f R − f R+ ]

a) A normal distribution of measurement errors.

b) A single value per variable.

c) A “steady-state” system.

a) Substantiated by the central limit theorem.

b) Also valid for means.

c) No plant is truly at “steady-state”.

Process oscillations occur. Therefore, it is said

that it is valid for a “pseudo-steady state”

system”

110

~

ER fR = 0

110

105

100

95

90

1

110

105

105

100

100

95

95

90

250

Tim e

90

1

Tim e

250

1

Tim e

250

Reconciliation of averages is equal to the average of reconciled

values using dynamic data reconciliation (Bagajewicz and

Jiang, 2000; Bagajewicz and Gonzales,2001).

That is, there is no need to adjust the variance-covariance

matrix for process variations.

Dynamic Data Reconciliation

Linear Case(after cooptation):

{

}

~

~

~

−1 ~

Min ∑ [ f Ri − f Ri+ ]T QRf−1[ f Ri − f Ri+ ] + [VRi − VRi+ ]T QRV

[VRi − VRi+ ]

∀i

~

~

dVR

B

= Af R

dt

~

Cf R = 0

When B=I, the Kalman filter can be used.

Dynamic Data Reconciliation

{

}

~

~

~

−1 ~

Min ∑ [ f Ri − f Ri+ ]T QRf−1[ f Ri − f Ri+ ] + [VRi − VRi+ ]T QRV

[VRi − VRi+ ]

∀i

~

~

dV R

B

= Af R

dt

~

Cf R = 0

Difference Approach: Darouach, M. and M. Zasadzinski, 1991, Rollins, D. K.

and S. Devanathan, 1993.

(

)

~

~

~

B VR ,i − VR ,i = AFR ,i

~

CFR ,i = 0

An algebraic system of equations follows.

Integral Approach: Jiang and Bagajewicz, 1997.

s

f R ≈ ∑ α kR t k

k =0

s

BR [VR − VR 0 ] = BR ∑ ω t

The technique estimates the coefficients of polynomials.

k =0

R k +1

k +1

s

= AR ∑

α kR

t

k =0 k + 1

k +1

Nonlinear Data Reconciliation

N

Min ∑ [ ~

x M (t k ) − z M ,k ]T Q −1 [ ~

x M (t k ) − z M ,k ]

k =0

d~

x1

= g1 ( ~

x1 , ~

x2 )

dt

g 2 (~

x1 , ~

x2 ) = 0

Applied in practice to steady state models with material, component

and energy balances. In the dynamic case, orthogonal collocation

was used (Liebmann et al, 1992) or linearization (Ramamurthi et

al.,1993) or use of DAE (Albuquerque and Biegler, 1996).

Gross Errors

Types of Gross Errors

105

104

103

102

101

Biases

Leaks (Model departures)

True outliers

Temperature

100

99

98

97

96

95

1

250

Ti m e

104

103

102

101

100

99

98

97

96

0

Tim e

250

Hypothesis Testing

Global Test (Detection)

γ = r ( E R QR E RT ) −1 r

H 0 : µ RT ( E R QR E RT ) µ R = 0

H 1 : µ RT ( E R QR E RT ) µ R ≠ 0

Distributi on : Chi − Squared

Nodal Test (Detection and Identification)

Z =n

N

i

1/ 2

ri

( E R QR ERT ) ii

H 0 : µ r = 0

H 1 : µ r ≠ 0

Distributi on : Normal

Maximum Power versions of this test were also developed. Rollins et al (1996)

proposed an intelligent combination of nodes technique

Hypothesis Testing

Principal Component (Tong and Crowe, 1995)

Wr : matrix of eigenvectors of ( E R QR ERT )

Λr : matrix of eigenvalues of ( E R QR ERT )

pr = W T r

pr ~ N (0, I )

H 0 : W T µ r = 0

H 1 : W T µ r ≠ 0

Distributi on : Normal

Hypothesis Testing

Measurement Test

Z χLCT

~

fi − fi +

=

~

(QR ) ii

H 0 : φi − f i = 0

H 1 : φi − f i ≠ 0

Distributi on : Normal

This test is inadmissible. Under deterministic

conditions it may point to the wrong location.

Hypothesis Testing

Generalized Likelihood ratio

λ = sup

∀i

Pr{r H 1 }

Pr {r H 0 }

H 0 : µ r = 0

H 1 : µ r = bAei

Distributi on : Chi − Squared

exp{−0.5( r − bAei )T ( E R QE RT ) −1 ( r − bAei )}

λ = sup

exp{−0.5r T ( E R QE RT ) −1 r}

∀b ,i

Leaks can also be tested.

Gross Error Detection in

Nonlinear Systems

+ Linearization

+ Estimates from solving the Nonlinear problem and the

usual tests.

+ Nonlinear GLR (Renganathan and Narasimhan, 1999)

OF ( no gross error assumed )

λ = sup

i OF (ith gross error assumed )

Multiple Error Detection

Serial Elimination

Apply recursively the test and eliminate the measurement

Serial Compensation

Apply recursively the test, determine the size of the gross

error and adjust the measurement

Serial Collective Compensation

Apply recursively the test, determine the sizes of all gross

error and adjust the measurements

Multiple Error Detection

Unbiased Estimation

One shot collective information of all possible errors

followed by hypothesis testing. Bagajewicz and Jiang,

2000, proposed an MILP strategy based on this.

Two distributions approach

Assume that gross error have a distribution with larger

variance and use maximum likelihood methods

(Romagnoli et al., 1981) (Tjoa and Biegler, 1991) (Ragot

et al., 1992)

Multiscale Bayesian approach. Bakshi et al (2001).

EQUIVALENCY THEORY

EXACT LOCATION DETERMINATION IS NOT

ALWAYS POSSIBLE, REGARDLESS OF THE

METHOD USED.

MANY SETS OF GROSS ERRORS ARE EQUIVALENT,

THAT IS, THEY HAVE THE SAME EFFECT IN DATA

RECONCILIATION WHEN THEY ARE COMPENSATED.

BASIC EQUIVALENCIES

In a single unit a bias in an inlet stream is

equivalent to a bias in an output stream.

S1

S2

Measurement

Case 1 Reconciled data

Estimated bias

Case 2 Reconciled data

Estimated bias

S1

4

3

1

4

S2

3

3

4

-1

BASIC EQUIVALENCIES

In a single unit a bias in a stream is equivalent to

a leak

S1

S2

Leak

M easurem ent

Case1

Reconciled data

Estim ated bias/leak

Case2

Reconciled data

Estim ated bias/leak

S1

4

4

S2

3

3

4

4

-1

Leak

1

EQUIVALENCY THEORY

S6

S1

S2

S5

S3

S4

For the set Λ={S3, S6} a gross error in one of them can be alternatively

placed in the other without change in the result of the reconciliation. We

say that this set has Gross Error Cardinality Γ(Λ)=1. ONE GROSS

ERROR CAN REPRESENT ALL POSSIBLE GROSS ERRORS IN THE

SET.

GROSS ERROR DETECTION

TWO SUCCESFUL IDENTIFICATIONS:

Exact location

Equivalent location

THIS MEANS THAT THE CONCEPT OF

POWER IN LINEAR DATA

RECONCILIATION SHOULD BE REVISITED

TO INCLUDE EQUIVALENCIES

COMMERCIAL CODES

Package

Nature

Offered by

IOO (Interactive

On-Line Opt.)

Academic

Louisiana State University

(USA)

DATACON

Commercial

Simulation Sciences

(USA)

SIGMAFINE

Commercial

OSI

(USA)

VALI

Commercial

Belsim

(Belgium)

ADVISOR

Commercial

Aspentech

(USA)

MASSBAL

Commercial

Hyprotech

(Canada)

RECONCILER

Commercial

Resolution Integration

Solutions (USA)

PRODUCTION

BALANCE

Commercial

Honeywell

(USA)

RECON

Commercial

Chemplant Technologies

(Czech Republic)

While the data

reconciliation in all these

packages is good, gross

error detection has not

caught with developments

in the last 10 years.

Global test and Serial

Elimination using the

measurement test seem to

be the gross error detection

and identification of

choice.

INSTRUMENTATION UPGRADE

(The inverse engineering problem)

Given

Data Reconciliation (or other)

monitoring Objectives

Obtain:

Sensor Locations

(number and type)

INSTRUMENTATION DESIGN

Minimize Cost (Investment + Maintenance)

s.t.

-Desired precision of estimates

-Desired gross error robustness

Detectability, Residual Precision, Resilience.

-Desired reliability/availability

Design of Repairable Networks

EXAMPLE: Ammonia Plant

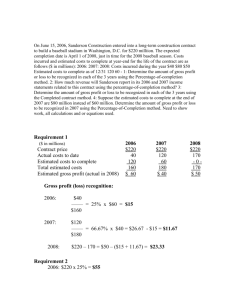

Table 3: Optimization results for the simplified ammonia process flowsheet

Repair

Rate

Measured

Instrument

Variables

Precision

(%)

5

S8

S6

1

1

S5

6

4

S3

S1

2

S2

2

4

3

20

Precision(%)

(S2)

(S5)

Precision

Availability

Availability(%)

(S1)

(S2)

(S7)

(S5)

S4

S7

Cost

S1 S4 S5

S6 S7 S8

311132

S4 S5 S6

S7 S8

33131

S4 S5 S6

S7 S8

33133

S4 S5 S6

S7 S8

33133

2040.2

1699.8

1683.7

1775.2

0.8067

0.9841

0.9021

1.2893

1.2937

0.9021

0.9283

1.9712

0.9222

1.9928

2.0086

0.9062

1.2313

1.9712

0.9636

1.9963

2.0086

0.9511

1.2313

1.9712

0.9983

1.9963

2.0086

0.9969

There is a minimum in cost as a function of the repair rate.

This allows the design of maintenance policies.

Upgrade

Upgrade consists of any combination of :

Adding

instrumentation.

Replacing instruments.

Relocating instruments (thermocouples,

sampling places, etc).

Upgrade

Example

Flowmeters 3%

Thermocouples 2oF

S8

S6

S1

U1

S2

U2

S7

S3

U3

S9

S5

S8

Case

σ U∗

1

4.00

4.00

4.00

2

3

4

5

6

2.00

2.00

1.50

2.40

2.20

2.00

2.00

1.50

2.30

1.80

2.00

2.20

2.20

2.20

2.40

1

σ U∗

2

Reallocation and/or addition of

thermocouples as well as a

purchase of a new flowmeter

improve the precision of heat

transfer coefficients

S4

σ U∗

3

c

Reallocations

New

Instruments

3.2826 1.9254 2.2168

100

uT1 , 2,T6

-

1.3891

1.3492

2.0587

1.7890

3000

5250

1500

1600

-

T2, T6

F4, T2, T6

T6

T6

σU

1

σU

2

1.5148

1.3664

1.8174

1.6827

σU

3

2.1935

2.1125

2.1938

2.2014

uT1 , 2,T2

Latest Trends

+ Multiobjective Optimization (Narasimhan and Sen, 2001, Sanchez

et al, 2000): Pareto optimal solutions (cost vs. precision of

estimates are build)

+ Unconstrained Optimization (Bagajewicz 2002, Bagajewicz and

Markowski 2003): Reduce everything to cost, that is find the

economic value of precision and accuracy.

FAULT DETECTION

Given the possible faults, design a sensor

network that will detect and differentiate the

faults.

Bhushan

and Rengaswami (2000, 2001)

CHALLENGES

Academic: Multiple Gross Error Identification

Gross Errors for Nonlinear Systems.

Multiobjective Methods. Unconstrained Methods

Industrial: Dynamic data reconciliation.

Gross Error Handling.

Sensor Upgrades

CONCLUSIONS

• Data Reconciliation is an academically mature field.

• It is a must when parameter estimation (mainly for on-line

optimization) is desired.

• Commercial codes are robust but lack of up to date gross

error detection/location techniques.

• Instrumentation Upgrade methodologies have reach maturity

• Industry understands the need for upgrading, but academic

efforts have not yet reached commercial status. They will, soon.