Understanding patents,

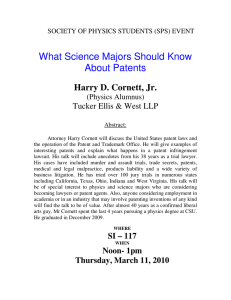

advertisement