JANE PINCUS

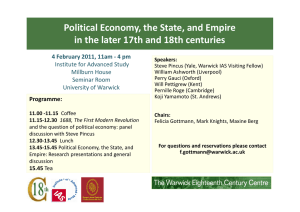

advertisement