Ovid's Poetics of Illusion

advertisement

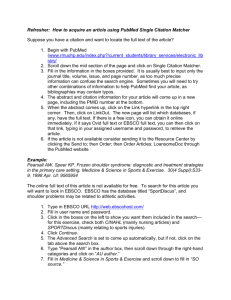

Philip Hardie, Ovid's Poetics of Illusion (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002), x + 365pp., 12 b&w illustrations, ISBN 052180087 In the last few years there has been a resurgence of interest in Ovid sparked by Ted Hughes’ Tales from Ovid (1997) and evidenced by the continuing fascination with Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, which draws heavily on Ovids story of Tereus and Procne. Philip Hardie’s book, Ovid’s Poetics of Illusion, is a major new study which touches on the whole of Ovid’s work, from the Amores to the poetry written during his exile. Hardie presents Ovid as ‘the most slippery of writers’ and focuses on the duplicity which he sees as the central characteristic of his work, particularly in the Metamorphoses. Not only are there shifts of meaning within the words of the Latin text but Ovid’s characters, and the stories themselves, are capable of constant reinterpretation to suit the preoccupations of the time. Hardie’s book explores the ways in which the poet works on the reader’s imagination to conjure characters and events which seem to possess a vivid life of their own. In his introductory chapter, Hardie says that the emphasis of his book is on this illusion of presence rather than ‘fictionality’ and he considers how Ovid creates this sense of presence through desire: ‘Illusions of presence are fuelled by the desire of the lover, the desire of the mourner ... as well as by the desire which works of art and texts stimulate in their viewers and readers’. He develops his ideas with detailed readings of Ovidian texts supported by critical responses selected from writers and artists who, as he admits, have held Ovid in high regard. Hardie ranges across different centuries and a variety of disciplines, from poetics and rhetoric to philosophy, religion, art and politics. He also revisits some of the more familiar stories of transformation from Ovid’s Metamorphoses including Narcissus, Apollo and Daphne and Pygmalion. The concluding chapter of Hardie’s book deals with the continuing influence of Ovid on the modern novel. The Renaissance was particularly alive to the conceits, selfconsciousness and ironic wit in Ovid’s work. Renaissance literary scholars will find much to interest them in Hardie’s critical analysis of the reception of Ovid’s poetry during this period. Petrarch has often been claimed to mark the beginning of a Renaissance and Hardie examines the influence of Ovid in the Rime Sparse with the endlessly repeated absent presence of Laura. He looks at Ovidian illusionism in the use of the Pygmalion story in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale and Shakespeare’s engagement with time and fame in the Sonnets. There is also an analysis of Ben Jonson’s play Poetaster, with its dramatised literary and personal criticism of Ovid. 2 Hardie’s Ovid’s Poetics of Illusion covers a wide field and, as the author comments, is ‘just one snapshot in the album of the reception of his works over the last two millennia’. However, Hardie brings fresh insights into the work of a classical writer whose influence has permeated much of our literary heritage and continues to be a source of inspiration today. Ann Tollett University of Warwick 3