Document 12908338

advertisement

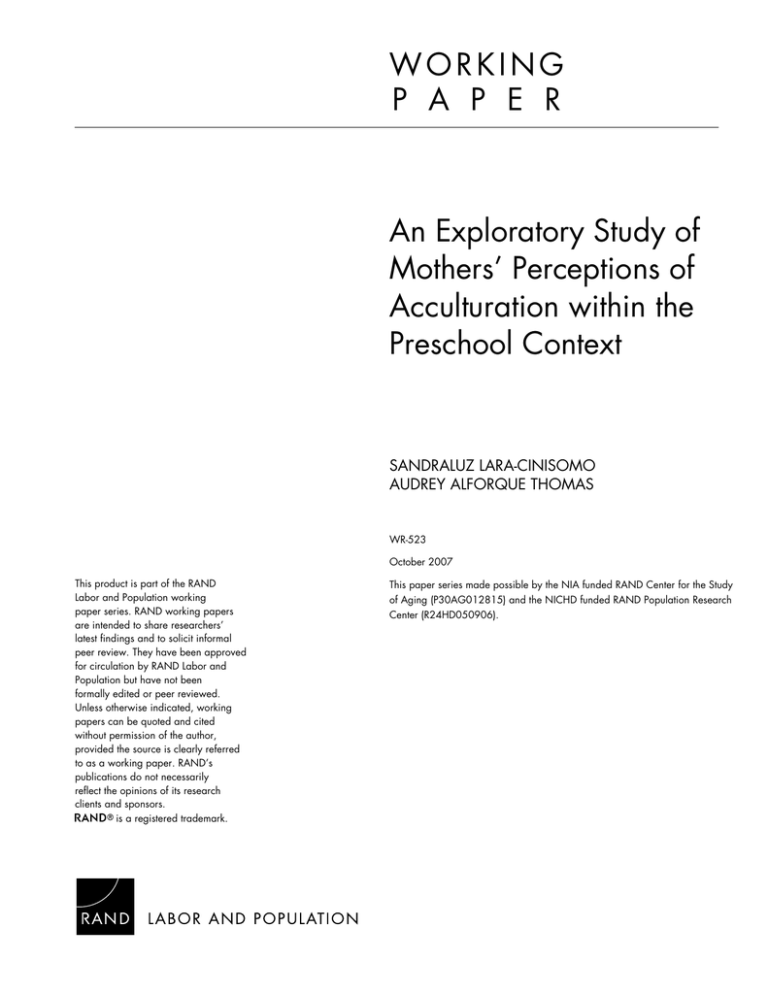

WORKING P A P E R An Exploratory Study of Mothers’ Perceptions of Acculturation within the Preschool Context SANDRALUZ LARA-CINISOMO AUDREY ALFORQUE THOMAS WR-523 October 2007 This product is part of the RAND Labor and Population working paper series. RAND working papers are intended to share researchers’ latest findings and to solicit informal peer review. They have been approved for circulation by RAND Labor and Population but have not been formally edited or peer reviewed. Unless otherwise indicated, working papers can be quoted and cited without permission of the author, provided the source is clearly referred to as a working paper. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. is a registered trademark. This paper series made possible by the NIA funded RAND Center for the Study of Aging (P30AG012815) and the NICHD funded RAND Population Research Center (R24HD050906). Acculturation and Maternal perceptions An Exploratory Study of Mothers’ Perceptions of Acculturation Within the Preschool Context Sandraluz Lara-Cinisomo, Ph.D. RAND Corporation Audrey Alforque Thomas Harvard University 1 Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 2 Abstract This exploratory study examines the mother’s perceptions of her preschooler’s acculturation process, using qualitative methods to collect data from six Latino immigrant mothers about their own acculturation and that of their preschool child. Three patterns emerged: parallel dyadic acculturation, vertex dyadic acculturation, and intersegmented dyadic acculturation. One mother-child dyad were coded as parallel, defined by the complete disconnect between mother and child acculturation. Three mother-child dyads were code as vertex dyad, which is defined as the mother and child starting at the same stage of acculturation and then deviating from each other as the child’s acculturation accelerates and mother’s decelerates. Two dyads fell in the third dyad, intersegmented, where mother and child acculturation processes converge and separate at various points. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 3 Introduction The process of acculturation is a very personal one, one that is influenced by both an individual’s experience with members of her own group and those in the host society and by such outside forces as discrimination and marginalization. These internal and external acculturation processes often differ between parent and child for several reasons. First, children tend to integrate at a faster rate and with less stress than the parent (Padilla, Alvarez, & Lindholm, 1986). Children also have more opportunities to practice, acquire, and experiment with U.S. cultural values and behaviors because of their interactions within a school setting, whereas immigrant parents may live within a cultural enclave that fosters the use of the native tongue and promotes traditional values not found in U.S. society. Second, the child’s experience with discrimination may differ dramatically from his parents. At times, the child may not be aware that he/she is being discriminated against. In contrast, an adult or parent may be able to decipher others’ behaviors as discriminatory. The immigrant adult may also experience more encounters, such as shopping and interacting with communities, where discrimination is more likely to occur. Commitment is the third reason adult and child acculturation processes differ. The U.S.-born child of immigrants and young immigrant child experience less of a connection to their country of origin primarily because of limited experiences in the homeland (Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 1995). Differing acculturative styles may create friction within the family; then again, if a parent and child have differing acculturation processes, they may complement each other. Recent research has focused on how acculturation to U.S. society in parents and children affects the social, emotional, and educational outcomes of the children. Some studies focus on the degree of acculturation to U.S. society and disagree on whether it is detrimental to children Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 4 (Epstein, Botvin, & Diaz, 2001) or protective (Martinez, DeGarmo, & Eddy, 2004). Recent research has also focused on the acculturation styles of parents and children and on how differences or similarities in these styles affect the parent-child relationship and children’s academic, behavioral, and emotional outcomes (Farver, Narang, & Bhadha, 2002; Ibanez, Kuperminc, Jurkovic, & Perilla, 2004; Vega, Khoury, Zimmerman, Gil, & Warheit, 1995; Weisskirch & Alva, 2002). Portes and Rumbaut’s (2001) typology of acculturation across generations is the prevailing model on immigrant parent-child experiences and children’s academic, social, and emotional outcomes. It is based on segmented assimilation theory (Portes & Zhou, 1993). Their model focuses on acceptance of U.S. customs and the English language and insertion into the ethnic community. In their model, parent-child differences in acculturation are indicative of dissonant acculturation and can lead to poor academic and social outcomes for the child. Parentchild similarities in acculturation can mean complete assimilation into mainstream U.S. culture (consonant acculturation) or selective acculturation, which occurs when parent and child embrace the customs and language of their host country but still cling to the beneficial aspects of their native culture. Both consonant and selective acculturation portend favorable academic and social outcomes for the child. Many of the studies on the positive effects of selective acculturation on children’s social and academic outcomes (Bankston & Zhou., 1995; A. Portes & Rumbaut, 2001; Romero, Robinson, Haydel, Mendoza, & Killen, 2004) focus on junior high school and high school (Battle, 2002; Epstein, Botvin, & Diaz, 2001; Farver, Narang, & Bhadha, 2002; Ibanez, Kuperminc, Jurkovic, & Perilla, 2004; Martinez, DeGarmo, & Eddy, 2004; P. R. Portes & Zady, 2002; Vega, Khoury, Zimmerman, Gil, & Warheit, 1995; Xiong, Eliason, Detzner, & Cleveland, Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 5 2005). A few empirical studies look at elementary school-age children (Romero, Robinson, Haydel, Mendoza, & Killen, 2004; Weisskirch & Alva, 2002). Yet it is equally important to explore the acculturation process of young children at the preschool or kindergarten levels. This time period is crucial because it often marks the beginning of the child’s immersion in U.S. culture. Anthropologists have found that cultural discontinuities between the child and U.S. culture occur primarily with the onset of schooling (Spindler, 1974; Trueba, 1993). Similarly, cultural discontinuities develop in an immigrant family as the child begins to negotiate new practices adopted from the host society and those valued in her home. Such discontinuities also result when the immigrant parent expresses disapproval of the child’s adoption of mainstream behaviors. Therefore, researchers argue that differing acculturation processes exist within the parent-child dyad and are most observable with the onset of child schooling. However, the parent may encourage the child to integrate into U.S. society while also becoming acculturated herself. The literature that deals with immigrant families with young children focuses on cultural assimilation/maintenance and language skills/development. In a case study of 25 Mexican immigrant families, Reese (2001) found that parents want their children to benefit from the U.S. educational and economic opportunities but would also like to shield their children from U.S. culture, which they perceive as a threat to ideals of respect and famialism. Recent immigrants tend to stress the moral development of their preschool-age children over academic skills (Farver, Xu, Eppe, & Lonigan, 2006; Gallimore & Goldenberg, 2001; Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006) and are disappointed that preschool teachers seem preoccupied with literacy and numeracy (Reese, 2001). Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 6 There is a great deal of literature on young children from immigrant families and their language ability. Children’s linguistic and literacy outcomes depend on the language of instruction at school, language exposure at home, and language use within the community. Studies show that immigrant Latino parents are eager to have their preschoolers learn English and retain Spanish (Reese, Goldenberg, & Saunders, 2006; Worthy, 2006; Worthy & RodríguezGalindo, 2006). In an in-depth qualitative study, Worthy and Rodríguez-Galindo (2006) found that when parents are proactive about promoting bilingualism, children become fluent in written and spoken English and Spanish. Biliteracy is academically advantageous. The onset of a child’s schooling is an interesting time, because changes in the child’s environment may manifest in changes in the parent-child interaction. Using in-depth interviews with immigrant women, we examine the acculturation to U.S. society and the retention of native culture in women whose children are in preschool. In addition, we explore the relationship between these women and their children—in particular, their expectations for their child’s acculturation to U.S. society and retention of native culture. As noted above, the existing literature focuses mainly on the social, academic, and linguistic outcomes of children. In this exploratory study, we focus on the mothers and their perceptions of their mother-child interaction, especially as it is affected by cultural assimilation and/or cultural retention. We acknowledge that fathers are an integral part of the parenting and family unit (Ortiz, 2004; Rodriguez, Davis, Rodriguez, & Bates, 2006). However, this exploratory study examines the preschooler’s acculturation process through the eyes of his mother—his primary caretaker in these cases. In addition, this study examines the mother’s acculturation process within the context of her preschooler’s school experience. Method Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 7 Site We recruited participants from a Healthy Start Program at a community program within an elementary school located in the City of Cudahy, a predominantly Latino immigrant community in Southern California. Healthy Start is a comprehensive, community-based program that offers a number of services to the community, among which are English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, child care/preschool for children of ESL students, parent education courses, vocational adult education courses and access to health care. Participants Six mothers agreed to participate in the study. The mean age of the participants is 30, the mean income for the six families is $17,000, and the mean family size is 4.5. All the participants were immigrants from Latin American countries. One respondent emigrated from Honduras, while the other five emigrated from Mexico. The mean number of years in the United States was 7.8 years. Spanish was the dominant language in each of the six homes. Five of the participants live in the city of Cudahy, California. The sixth participant lives in a predominately Latino immigrant community two miles northwest of Cudahy in the City of South Gate. All the respondents live with their spouse and children. Two families have extended family members residing in their home. The mean number of children per family is 4, with ages ranging from 2 to 11. The mean target child age was 3.5 years. Three boys and three girls were included in our study. Four of the children spoke Spanish with their mother and two spoke both English and Spanish. However, according to participants, five of the six target children could speak both English and Spanish. All target children participated in the Healthy Start preschool program. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 8 Observation Period at School Site to Establish Trust To establish trust with the ten volunteer mothers in the study site, classroom teachers gave the lead author permission to participate in the daily classroom activities. All the parents in the preschool program consented to the author’s participation. During daily activities, group conversations often spontaneously formed during the children’s “outside” play. The topics of discussion varied from children’s emotional needs to mother’s perception of their preschooler’s school performance. At times, parents informally compared their children with one another. Fathers were not present during these conversations and interactions, because they worked during regular school hours when mothers volunteered to help in the classroom. In many cases, fathers worked more than one job at a time and were not able to participate in their children’s preschool experience. The author did not conduct any formal or informal interviews or assessment during the spontaneous conversations. At the end of the eight-week period, mothers were invited to participate in an in-depth interview about their perceptions of their preschooler’s acculturation experience and their own acculturation process. Six of the ten mothers agreed to participate. Data Collection Procedures The interviewer administered an in-depth, semi-structured interview, which gave parents an opportunity to give open-ended answers and provide rich information on the subject matter and on related issues. We conducted interviews in participant homes or at the school site, depending on the parent’s preference. Four of the interviews took place in the respondents’ homes, while the other two took place at the school site. Interviews lasted 45 minutes on average. All interviews were conducted in Spanish, and fathers were not present for the interview. In five of the six interviews, the preschool child was present during the interview. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 9 We recorded the interviews with the participants’ consent and transcribed them verbatim for analysis. The interviewer gave children a gift as a token of appreciation, and mothers received modest monetary compensation. Mothers were interviewed about use of language (e.g., English and Spanish) in the home and whether cultural values were discussed in the home. We asked parents about their child’s adoption of mainstream practices. For example, one question was, “Have you noticed that your child has American ideas?” To ascertain in more detail how parents felt about their child’s acculturation, we included projective questions. For example, we asked, “How would you feel if your daughter decided to speak only English? Data Analysis We used Grounded Theory Methodology (Glazer & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to analyze the interview transcripts. Certain responses or “mentions” about language use, cultural values, and responses to children’s acculturation occurred repeatedly over the interviews. We created codes for these responses and applied them to each transcript. Two researchers separately coded each interview. The coders then compared codes to verify accuracy. Using the codes, we grouped similar responses together. From these empirical groupings, types of dyadic acculturation patterns emerged. The acculturation patterns are a theoretical representation of our analysis of the transcripts; thus, the patterns are grounded in the data. Results Three types of dyads emerged from the data, as shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This first typology is referred to as a parallel dyad, in which the mother’s and child’s acculturation processes are completed disconnected as coded in the data. In the second Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 10 typology, referred to as a vertex dyad, the mother and child have common acculturation processes at the onset, but the commonality is hypothesized to deviate and the two acculturation processes go their own ways. In the third typology, referred to as an intersegmented dyad, the acculturation processes of the mother and child meet at various points and depart at others. Based on our analysis, one mother fit the parallel dyad, three mothers fell into the vertex dyad, and the remaining two mothers fit into the intersegmented dyad. We discuss each below. We used pseudonyms for all the mothers and children. Table 1 provides a summary of key characteristics for each of the three dyads. Parallel Dyad This first dyad is characterized by conflicting patterns of acculturation between parent and child. The parent resists integrating into the host society and similarly discourages her child from acculturating and incorporating new behaviors into the family cultural schema. Although the mother may have some of the host society’s practices, such as learning English, she still insists that the child not participate in mainstream behaviors in her presence or in the home, such as using English in the home. In the one case that fit this pattern, the mother emigrated from Mexico with her husband six years ago. Mrs. Moran has an eleventh-grade education from Mexico. Since her arrival, she has resided in the City of Cudahy with her spouse and children. Mrs. Moran attended ESL courses for two years prior to taking a position as a volunteer childcare provider at the study site. According to Mrs. Moran, she can read, write, and speak English “un poco” (a bit), but does not practice speaking it. When asked if she could speak English, she responded by saying, “Yo, pues, yo tengo mucho vocabulario pero no, no lo habla nada” (I, well, I have a large vocabulary, but no, no I don’t ever speak it). When asked about her child’s use of English, her response Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 11 resonates with her own practices. Mrs. Moran’s response to the question, “And has he begun to speak English to you?” was “Palabras…a mi no me gusta que hable Ingles aqui en la casa…Yo le digo ‘que lo quiera platicar alla con sus amigitos…aqui en la casa No.’” (Words…I don’t like him speaking English at home…I tell him ‘whatever you want to talk about talk over there with your friends…not at home!’). The child, however, felt differently. When Mrs. Moran said, “Aqui nadie hablamos Ingles,” (Here [at home] no one speaks English), the target child, Arturo, immediately responded, “yo si!” ( . . . I do!). With regard to discussions about cultural values, Mrs. Moran does not discuss them with her son. However, when asked about her son’s adoption of U.S. cultural practices, she referenced his eating habits. According to Mrs. Moran, Arturo prefers hamburgers, hot dogs, and pizza to chicken soup and tortillas. When asked about her reaction to this, she said it bothers her, but primarily because American food does not provide the same nutritional values as her homemade chicken soup. While this may be true from a nutritional standpoint, this still amounts to making value judgments on American eating habits versus Mexican meals. When asked about the importance she places on her child’s interactions with members from other ethnic/racial groups, Mrs. Moran said she places “little importance” on it. Vertex Dyad The second dyad is characterized by a parent who enthusiastically experiences her acculturation process by attending ESL classes. The acculturation process is a shared experience between the two, with one teaching the other different behaviors from the mainstream society. Still, this parent may not immerse herself in the host society as much as the child may, drawing limits on the number of mainstream behaviors she adopts; however, she does support her child’s Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 12 acculturation. This is translated into a mother and child who start at the same point in the acculturation process, but divert at some point and go off into their own patterns. Three of the mothers we interviewed fit this pattern. The mean number of years these respondents have been in the United States is 6.3 years. The mean level of education is 7.3 years, all of which was in their country of origin (Mexico and Honduras). Two of the respondents did not consider themselves able to speak, read, or write English, while the third said she could read, write, and speak English “a little.” All have attended ESL classes and participated in courses such as basic computer instruction and child development. Among the three mothers who fit into the vertex dyad, two have the most experience with U.S. schools: Mrs. Castro has volunteered for six years and Mrs. Ramirez has been a volunteer for three years in her daughter’s school. The children of all three mothers have attended school only in the United States. All three mothers said that their children speak English in the home. Although they did not consider themselves equipped to teach their children English, they promoted the use of English by encouraging their children to teach them and by teaching them the little English they do know. Mrs. Gutierrez, an immigrant from Honduras, a mother of a two-year-old preschool toddler, shared examples of teaching her son simple English commands and then modeling the appropriate behavior. “Le digo, ‘Give me a kiss’ y el no mas se rei y yo le enseño que me de un beso.” (I tell him, ‘Give me a kiss’ and he just laughs then I show him to give me a kiss.) Although these mothers encourage and promote the use of English, they do not feel they will acquire English proficiency themselves. Characteristic of the vertex dyadic mother is an overt value placed on bilingualism. Regardless of their English proficiency, they all promoted the use of English and Spanish in the Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 13 home. When asked how they address the issue of bilingualism, respondents said that they rely on their children to help them learn English so they can understand what their child is saying and so they are not kept out of the loop. The child’s acculturation is much faster than that of the parent, and it is expected that the vertex dyadic child will eventually leave her parent behind; however, this common acculturation process established early on may provide for a sound foundation. The vertex dyadic mothers in this study indicated that discussions about ethnicity were limited, but they said they used the importance of the family as a means of limiting the child’s adoption of U.S. cultural values. These mothers acknowledge the importance of acquiring the English language but noted that it was important not lose sight of the value of maintaining Spanish. Although the vertex dyadic mother and her child do not explicitly discuss ethnicity, bilingualism served as the bridge missing from the parallel dyad. Intersegmented Dyad The third dyad, referred to as the intersegmented dyad, is characterized by the parentchild dyad’s repeated shared acculturation. The immigrant parent and her child exchange values acquired as a result of contact with the host society. Moreover, the mother and child in the intersegmented dyad share a mutual respect for their native culture. This is most evident in the intersegmented mothers’ own acculturation processes. This mother attends ESL classes and becomes a part of certain mainstream institutions, but she holds on to such native cultural values as collectivism and traditional foods. Still, while she is involved in her own acculturation process, this parent monitors her child to make sure the child does not reject traditional values Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 14 but instead complements those values with new behaviors gained from the host society; she makes sure that her child is always in touch with her cultural heritage. In the intersegmented parent-child dyad, conversations about ethnic pride and prejudice are commonplace. The intersegmented dyadic mother makes explicit the importance of maintaining one’s ethnic ties while incorporating behaviors of the host society. She ensures the native culture stays alive by teaching her child ethnic values. For example, one mother said, “En mi familia yo [les] estoy ensenandoles sus valores…Yo pienso que las formas de hablar (las idiomas) puede uno conseguirla y no necesariamente uno va dejar su cultura por hablar el Ingles. Yo creo que si [tendran tradiciones Mexicanas cuando esten grandes] porque los valores agarran desde chiquitos y creo que con la cultura que crescan cambiaran qualquier cosita, pero no creo que cambien toda[las tradiciones].” (…In my family, I’m teaching them values…I think we can acquire other ways of speaking [other languages] and not necessarily lose out culture just because we speak English. I think they will [maintain Mexican traditions] because the values they gain begin when they are small and I think that with the culture they grow up with small changes will be made to their traditions but not much.) Mrs. Silva (above) clearly states her belief that cultural values are formed early in life and that they are relatively stable over time. Thus, the intersegmented dyadic mother perceives new behaviors as adding to the existing cultural schema. In addition, she ensures that aspects of the new culture are an integral part of her child’s life. “Y usted como se sinteria si ellos tuverian mas ideas Americanas que Mexicanas?” (How would you feel if they [the children] adopted more American ideals than Mexican?) asked the interviewer. “…Pues yo se que estan en su pais.” (Well, I know they’re in their country.) Mrs. Silva responds with a sense of security and acceptance. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 15 In our sample, Mrs. Vera and Mrs. Silva, the two mothers in this dyad, had the highest number of years in the United States—9 and 14 years, respectively. Each of the intersegmented dyadic mothers has engaged in formal English learning programs. The intersegmented dyadic mother is enthusiastic and involved in her own development, as evidenced by her participation in various school-oriented activities. In both cases, respondents explicitly stated their plans for acquiring a vocational or bachelor’s degree. For example, Mrs. Silva said, “Yo le dije a mi esposo que yo quiero ir al colegio, que quiero ser maestra.” (I told my husband that I want to go to college, I want to become a teacher.) In a separate interview with Mrs. Vera, she was asked, “Es posible que ellos (su ninos) aprendan mas ingles? (It’s possible that they (your children) learn more English?) Mrs. Vera responded, “Por eso me voy a preparer…Yo quiero preparame para cuado ellos llegen ya a un ‘college’ para poderles ayudar.” (That’s why I’m going to get prepared…I want to prepare myself for when they attend college, so I can help them.) Moving on to the discussion about acquiring U.S. cultural values, the interviewer asked Mrs. Vera, “Usted [ha] observado que tienen (los ninos) ideas Americanas?” (Have you observed that your children have American ideas?) Her response was, “No, no porque como en mi familia yo estoy ensenandoles sus valores…le digo [a mi nina que todos tienen sus sentimientos y] no tiene nada que ver con el color del piel. Yo pienso que las formas de hablar puede uno conseguirla y no necesariamente uno va dejar su cultura por hablar en Ingles.” (No, no because in my family, I’m teaching them values…I tell [my daughter that everyone has feelings] and it has nothing to do with their skin color. I think we can acquire other ways of speaking (other languages) and not necessarily lose out culture just because we speak English.) Discussion Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 16 When it comes to analyzing acculturation—the process by which an individual acquires the culture on a particular country—more and more attention is focusing on the immigrant family. When immigrants come to the United States, many either bring young children with them or have children in the United States. As immigrants and their children negotiate U.S. society and culture, their experiences affect their own acculturation process, as well as the acculturation processes of others in their families. Characteristic of the mother in the parallel dyad is a need to maintain Spanish as the only language of the home, regardless of the child’s English proficiency and desire to speak English. It is hypothesized that this kind of dissonance creates much of the conflict in later observations in teen-parent dyads. A child who cannot freely incorporate the new behaviors he adopts (e.g., language, values, practices) into his repertoire will experience cultural discontinuity with his mother and may already be experiencing some level of discontinuity at school. The lack of constant acculturation can have negative consequences for school achievement and self-concept (A. Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). Results from the vertex and intersegmented dyads show that, according to mothers’ reports, the mothers are more closely aligned with their children’s current acculturation. Furthermore, they have a positive outlook on their child’s future acculturation. If this pattern continues, we can expect better academic outcomes for these children. In fact, Portes and Rumbaut (2001) suggest that consonant and selective adaptation are highly correlated with better child outcomes. This study adds to Portes and Rumbaut’s theory by considering parent-child acculturation as a process that changes over time and is dependent on multiple points of view within the dyad. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 17 Still, a mother’s perspectives on her child’s acculturation processes should not be determined by one time point or a current view. Instead, we should consider the mother’s own experiences and attitude toward her child’s acculturation process as it changes over time. For instance, the parallel dyad mother in this study personally experienced racism, which negatively affected her view of the United States and its values. One can argue that this mother may also be suffering from low self-esteem, depression, and isolation that may color her view of U.S. culture. In that same vein, one can argue that as this mother’s experiences in the United States improve, so will her attitude about and toward her child’s acculturation processes. Additionally, given the linear trajectory of the mean number of years in the United States across the three dyads shown in Table 1, one can argue that the patterns we observe are actually stages of acculturation. In time, one may observe a dyad that more closely resembles the intersegmented dyad. Similarly, one can hypothesize that the vertex dyad mother, assuming she continues to learn English and selectively adapts U.S. cultural practices, can also become an intersegemented mother. A longitudinal study that starts at the child’s onset of schooling and tracks the primary caregiver’s acculturation processes, as well as those of her child, will provide a more accurate picture. Study Limitations As with any small-scale, mixed-method study, this study has some limitations. First, we acknowledge that a sample size of six limits the generalizability of this study. However, given that this is the first study of its kind, our contribution is in bringing forth processes that are absent from the current literature about acculturation processes among parents and children, primarily very young children. Second, this study does not measure children’s English language acquisition independent of mother’s reports. To date, there is no reliable measure of children’s language acquisition. Therefore, mother reports were deemed the most reliable measure of Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 18 children’s English and Spanish skills. The third limitation of this study is that children were not interviewed. However, the aim of the study was to understand parent, in this case mother’s, and child acculturation processes as it unfolds within the context of children’s formal schooling experience (i.e., preschool), which had not been done previously. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 19 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the families who generously gave of their time. In addition, a special thanks goes out to Angie Preciado who assisted with the recruitment and data collection. Finally, this manuscript is dedicated to Maureen Haun, child advocate, a supporter of immigrant families, and a leader in child development whose time came too soon. This study would not have been possible without here support and guidance. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 20 References Bankston, C. L., & Zhou., M. (1995). Effects of Minority-Language Literacy on the Academic Achievement of Vietnamese Youths in New Orleans. Sociology of Education, 68(1), 117. Battle, J. (2002). Longitudinal Analysis of Academic Achievement Among a Nationwide Sample of Hispanic Students in One- Versus Dual-Parent Households. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 24(4), 430-447. Epstein, J. A., Botvin, G. J., & Diaz, T. (2001). Linguistic Acculturation Associated with Higher Marijuana and Polydrug Use among Hispanic Adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse, 36(4), 477-499. Farver, J. A., Narang, S. K., & Bhadha, B. (2002). East Meets West: Ethnic Identity, Acculturation, and Conflict in Asian Indian Families. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(3), 338-350. Farver, J. A., Xu, Y., Eppe, S., & Lonigan, C. J. (2006). Home Environments and Young Latino Children's School Readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 196-212. Gallimore, R., & Goldenberg, C. (2001). Analyzing Cultural Models and Settings to Connect Minority Achievement and School Improvment Research. Educational Psychologist, 36(1), 45-56. Glazer, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Halgunseth, L. C., Ispa, J. M., & Rudy, D. (2006). Parental Control in Latino Families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development, 77(5), 1282-1297. Ibanez, G. E., Kuperminc, G. P., Jurkovic, G., & Perilla, J. (2004). Cultural Attributes and Adaptations Linked to Achievement Motivation Among Latino Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(6), 559-568. Martinez, C. R. J., DeGarmo, D. S., & Eddy, J. M. (2004). Promoting Academic Success Among Latino Youths. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 26(2), 128-151. Ortiz, R. W. (2004). Hispanic/Latino Fathers and Children's Literacy Development: Examining involvement practices from a sociocultural context. Journal of Latinos and Education, 3(3), 165-180. Padilla, A. M., Alvarez, M., & Lindholm, K. J. (1986). Generational Status and Personality Factors as Predictors of Stress in Students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 8(3), 275-288. Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley: University of California Press. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 21 Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The New Second Generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530, 7496. Portes, P. R., & Zady, M. F. (2002). Self-Esteem in the Adaptation of Spanish-Speaking Adolescents: The Role of Immigration, Family Conflict, and Depression. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 24, 296-318. Reese, L. (2001). Morality and Identity in Mexican Immigrant Parents' Visions of the Future. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(3), 455-472. Reese, L., Goldenberg, C., & Saunders, W. (2006). Variations in Reading Achievement among Spanish-Speaking Children in Different Language Programs: Explanations and confounds. The Elementary School Journal, 106(4), 363-385. Rodriguez, M. D., Davis, M. R., Rodriguez, J., & Bates, S. C. (2006). Observed parenting practices of first-generation Latino families. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(2), 133-148. Romero, A. J., Robinson, T. N., Haydel, K. F., Mendoza, F., & Killen, J. D. (2004). Associations Among Familism, Language Preference, and Education in Mexican-American Mothers and Their Children. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 025(1), 34-40. Spindler, G. D. (1974). The Transmission of Culture. In G. D. Spindler (Ed.), Education and the Culture Process: Toward an Anthropology of Education. New York: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston. Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics in Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Suarez-Orozco, M., & Suarez-Orozco, C. (1995). Uncertain Journeys: Latinos in the United States. In Worlds Apart (pp. 82-143): Stanford University Press. Trueba, H. T. (1993). The Dynamics of Cultural Transmission. In H. T. Trueba, C. R. Rodriguez, Y. Zou & J. Cintron (Eds.), Healing Multicultural America: Mexican Immigrants' Rise to Power in Rural California. Bristol, PA: The Farmer Press. Vega, W. A., Khoury, E. L., Zimmerman, R. S., Gil, A. G., & Warheit, G. J. (1995). Cultural Conflicts and Problem Behaviors of Latino Adolescents in Home and School Environments. Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 167-179. Weisskirch, R. S., & Alva, S. A. (2002). Language Brokering and the Acculturation of Latino Children. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 24(3), 369-378. Worthy, J. (2006). Como si le Falta un Brazo: Latino Immigrant Parents and the Costs of Not Knowing English. Journal of Latinos and Education, 5(2), 139-154. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions 22 Worthy, J., & Rodríguez-Galindo, A. (2006). "Mi Hija Vale Dos Personas": Latino Immigrant Parents' Perspectives About Their Children's Bilingualism. Bilingual Research Journal, 30(2), 579-601. Xiong, Z. B., Eliason, P. A., Detzner, D. F., & Cleveland, M. J. (2005). Southeast Asian Immigrants' Perceptions of Good Adolescents and Good Parents. The Journal of Psychology, 139(2), 159-175. Acculturation and Maternal perceptions Table 1 Mother-Child Acculturation Typologies Type of Dyadic Acculturation Parallel Average Time in US 6.0 years Participation in US Institutions Some Vertex 6.3 years Extensive Ms. Herrera: “I tell her [her daughter], ‘I taught you how to add, now you have to teach me English.’” Intersegmented 11.5 years Extensive Mrs. Castro: “I think we can acquire other ways of speaking and not necessarily lose our culture just because we speak English.” Language Use Mrs. Moran: “I don’t like him [her son] speaking English at home.” 23 Acculturation and Maternal perceptions Figure 1 Parallel Dyad Mother Child 24 Acculturation and Maternal perceptions Figure 2 Vertex Dyad Child Mother 25 Acculturation and Maternal perceptions Figure 3 Intersegmented Dyad Mother Child 26