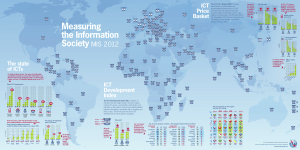

Measuring the Information Society Report 2014

advertisement