Self-Identified Sexual Orientation and the

Lesbian Earnings Differential

Michael E. Martell

Franklin and Marshall College

mmartell@fandm.edu

Mary Eschelbach Hansen

American University

mhansen@american.edu

December 15, 2014

Abstract

Two decades of research on differences in labor market outcomes by

sexual orientation has concluded that lesbian workers earn more than

heterosexual women. This research, however, is largely based upon

data that do not ask respondents about their own sexual orientation.

We are the first to use nationally representative data that includes selfidentified sexual orientation. We find evidence of a sizable wage penalty

for self-identified lesbians in 2008 and 2010. We show that using common behavioral proxies for sexual orientation overstates of the earnings

of lesbians in some years, but understates it in other years. Using the

different methods of identification leads to different conclusions about

the way the recession affected lesbians: It took much longer for the

wages of self-identified lesbians to recover.

Virtually all existing estimates of wage differentials by sexual orientation in

the U.S. depend on surveys that do not ask respondents about their own sexual

orientation. Researchers must classify respondents as gay, lesbian, or bisexual

using gender information together with reports of cohabitation status or sexual

behavior. That is, same-sex sexual orientation is implied if both members of

a co-habiting couple are of the same gender or if a respondent reports having

sexual relations with a partner of the same sex. Neither method is ideal. Using

the cohabitation status method fails to identify homosexual respondents who

are not currently living with a partner, while using the sexual behavior method

1

omits some sexually inactive homosexuals and includes respondents who would

not self-identify as heterosexual.

Nearly two dozen studies have used these methods of researcher identification to document an earnings penalty for gay men in the United States. About

half of these studies also document an earnings premium for lesbian women,

but half find no significant difference among women by sexual orientation.

There is some recent evidence of a declining lesbian premium (Cushing-Daniels

and Yeung 2009). To our knowledge, the only study that finds a statistically

significant earnings penalty for lesbian women in the U.S. is Carpenter (2005),

which is also the only study to date that uses self-reported sexual orientation.

Carpenter’s data are limited to California. In this paper, we use self-reported

sexual orientation and earnings data from the three most recent General Social

Surveys. We find that the method of classification matters for understanding

the evolution of wage differentials for lesbian, gay, and bisexual workers. We

observe a penalty for both self-identified and researcher-identified lesbians in

2008, confirming Carpenter’s findings. Further, we find that trends in wage

differentials between the self-identified and researcher-identified groups vary

in a meaningful way: Self-identified lesbians still had a substantial earnings

penalty in 2010, but researcher-identified lesbians did not.

We consider two reasons why the measured earnings penalty might differ

by method of identification. First, we consider differences in the composition

of the self-identified and researcher-identified groups. Second, we consider

differences in returns to human capital and family characteristics, as well as

differences by region and occupation. The data show that the recent economic

downturn affected both researcher-identified and self-identified lesbians negatively but it took longer for self-identified lesbians to recover. The observed

wage differentials in the 2008 correspond to the time leading up to the offi-

2

cial begining of the recession. While the lead up to the recession negatively

affected both self-identified and researcher-identified lesbians, the labor market outcomes for self-identified lesbians remained poor for a longer time than

outcomes for the group that includes women who have homosexual behaviors

but self-identify as heterosexual.

The Lesbian Wage Puzzle

Badgett (1995) was the first to note the asymmetry in wage differentials for

male and female homosexuals. She documented a wage penalty for behaviorally gay men, and found a positive but statistically insignificant wage premium for lesbians. The asymmetry in the results for gay men and lesbians

is difficult to reconcile with standard economic theory (for example, Becker

1957), so Badgett’s findings prompted a number of follow-up studies. In table

1 we summarize the results for lesbians in studies of the U.S.1

– Table 1 about here –

The follow up studies confirmed the asymmetry in wage differentials for

gay men and lesbians and documented large and significant earnings premia

for lesbians. Klawitter and Flatt (1998) were the first to find a significant

earnings premium for lesbians in their study of the impact of Employment

Nondiscrimination Acts (ENDAs) on the wages of gay men and lesbians. Many

studies subsequently documented a lesbian premium (Clain and Leppel 2001;

Berg and Lien 2002; Black, Markar, Sanders, and Taylor 2003; Blandford

2003; Comolli 2005), leading to a general consensus that lesbians appear to

be at an economic advantage relative to heterosexual women.2 This work

1

Most studies have been of the U.S, but studies have also found a lesbian premium in Sweden and the U.K. (Ahmed and Hammarstedt 2010; Ahmed, Andersson, and Hammarstedt

2011; Ahmed, Andersson, and Hammarstedt 2013; Arabsheibani, Marin, and Wadsworth

2004). In Greece however, there is evidence of a lesbian penalty (Drydakis 2014).

2

More recent research has begun to investigate the source of the lesbian earnings pre-

3

also consistently documented the significant earnings penalty for gay men,3

even though the authors used different data sources and different definitions

to identify homosexuals.

The two main data sources in the literature are the General Social Surveys

(GSS) and the U.S. Census. The Census does not ask questions about sexual behavior, but, as noted above, researchers identify same-sex cohabitants

as homosexual. Omitting single homosexuals may introduce bias if single respondents are systematically different from cohabiting respondents. Further,

the selection process into partnership varies between homosexual and heterosexuals (Carpenter and Gates 2008). All of the studies using the Census find

a statistically significant annual earnings premium for lesbians relative to heterosexual women, but the range of estimates of the premium is quite wide.

To illustrate: Baumle and Poston (2011) find a premium of four to nine percent, while Antecol, Jong and Steinberger (2008) find a premium of about 30

percent.

Since 1988, the GSS has asked respondents about their sexual behaviors

and sexual histories. Researchers using the GSS have available several measures of sexual behavior with which to identify homosexuals, which we discuss

in more detail below. None of these measures is a perfect proxy for sexual

orientation. Using sexual behavior to identify homosexual respondents omits

sexually abstinent respondents. More importantly, it wrongly classifies some

heterosexual respondents as homosexual and some homosexual respondents as

mium. A portion of the measured premium is attributable to the higher levels of human

capital that lesbians have relative to heterosexual women (Antecol, Jong, and Steinberger

2008). Further, the lesbian premium is larger among lesbians who have never been married

(to a man), which suggests that the lesbian premium may be related to decreased household

specialization for lesbians (Daneshvary, Waddoups, and Wimmer 2009). However, the lesbian premium remains intact after accounting for differentials in the presence of and return

to children in lesbian households (Jepsen 2007). We discuss this literature in greater detail

below.

3

An exception is Clarke and Sevak (2013), who find evidence of a premium for gay men

in recent years.

4

heterosexual. Misclassification is more likely among women than men because

heterosexual women are more likely than heterosexual men to have sex with

a member of the same sex (Laumann et al., 1994, Peplau, 2003). In 2008,

the GSS began asking respondents to identify their own sexual orientation.

The addition of information on self-identified sexual orientation represents a

substantial improvement in our ability to study lesbians in the GSS.

The GSS, unfortunately, has other weaknesses. It reports individual income

only within ranges. Most studies that use the GSS transform income ranges

into other measures or supplement income ranges with additional data from

other sources, as described below. Researchers using the GSS from the 1990s

have generally found a statistically significant lesbian income premium, with

estimates of the premium in the comparatively narrow range of 30 to 38 percent

(Berg and Lien 2002; Black, Markar, Sanders, and Taylor 2003; Blandford

2003).

Perhaps the greatest weakness of the GSS is that each year’s sample is

small. For this reason, researchers who use the surveys across a long span

of time have been more likely to obtain statistically significant results than

those who use only one or two years of the data. An exception is CushingDaniels and Yeung (2009), who use the longest run of GSS: 1988 through

2006. After correcting for selection into full-time work, they find no statistically significant differences in earnings by sexual orientation for either men or

women. Moreover, they find the familiar lesbian premium for married lesbians

only, and they find a (statistically insignificant) penalty for unmarried lesbians.

Cushing-Daniels and Yeung interpret this as evidence of a diminishing of the

premium over time, though Carpenter (2005) suggests that similar evidence

from the 1998-2000 GSS might be associated with changes in the propensity

of lesbians to work full time.

5

Carpenter (2005) is, to our knowledge, the only paper to date that utilizes

a survey conducted in the U.S. in which respondents are asked to identify their

own sexual orientation.4 The data are from the California Health Interview

Survey of 2001 and reveal no statistical difference in hourly wages for gay men

or lesbian women. However, in nearly all the specifications the coefficient on

sexual orientation is negative and in some specifications there is a statistically

significant wage penalty for bisexual women. While data for California are

unlikely to be representative of the entire U.S., it is possible that the difference

between Carpenter (2005) and the typical study is explained by differences

between self-identified and researcher-identified lesbians.

The Importance of Classification

The classification of workers as heterosexual or homosexual is important to

the estimation of wage differentials for two reasons. First, economic theories

that aim to explain the differences in the labor market experiences of lesbian,

gay, and bisexual (LGB) workers highlight the role of identity and disclosure

of an LGB orientation on individual economic outcomes. Second, errors in

classification may represent important omitted variable bias.

Consider the argument that a wage differential for homosexuals may be the

result of differences in patterns of household specialization (Black, Sanders,

and Taylor 2007). The logic is that a lesbian might invest in more human

capital than her heterosexual counterpart because she does not expect to have

a male partner who will specialize in market work. Conversely, a gay man

might invest less in his human capital than his heterosexual counterpart.5

4

Plug and Berkhout (2008) have self-identified sexual orientation of young men the

Netherlands. They find a penalty that they attribute to occupational selection. Carpenter

(2008) has self-identified data for Canada and find a lesbian premium.

5

Of course, this has not been observed empirically as nearly every study documents that

6

This theory of specialization is motivated by identity: We would not expect

women who sleep with women but identify as heterosexual to have different

human capital investments than the representative heterosexual woman.

The disclosure of sexual orientation is also key in theories of discrimination

against LGB workers. The application of standard theories of discrimination

to the LGB case requires employers, co-workers, or customers to observe the

sexual orientation of an LGB worker in order to discriminate against him or

her. Of course, LGB workers are able to conceal their sexual orientation, although the desire to disclose sexual orientation and live openly may motivate

LGB workers to choose tolerant workplaces and accept compensating differentials (Martell 2013a).

Finally, classification might matter if heterosexual women who sleep with

women are systematically different from other women in unobservable characteristics. For example, suppose women who identify as heterosexual and

sleep with women – an unconventional if not uncommon sexual practice – are

unconventional in other ways. If these women exhibit unconventional personal

behaviors in the workplace, their being identified as lesbian by researchers will

bias wage estimates of lesbians. Alternatively, some lesbians who self-identify

may exhibit traditionally masculine traits, such as assertive or risk-taking behaviors, while other lesbians may have workplace behaviors that conform more

to gender norms. In all of these examples, it is possible that an unobserved

personality characteristic – not sexual orientation – is the true cause of any

observed wage differential.

Classifying workers as heterosexual or homosexual based on their selfidentification is also important for analyzing the impact of public policies

such as ENDAs on LGB workers. Important differences between researchergay men and lesbians both have more education than their heterosexual counterparts.

7

identified and self-identified lesbians limit the ability of researchers to accurately measure the effectiveness of public policy directed towards self-identified

LGB workers. Self-identification is also important to measuring changes over

time in the labor market outcomes of LGB workers. If increased tolerance of

homosexuality is accompanied by increases in the likelihood that those engaging in same-sex sexual relations will self-identify, observed changes in wages

or employment outcomes for researcher-identified LGB workers may represent

changes in the composition of that group rather than changes in the actual

experiences of self-identified LGB workers.

This paper is the first to explore the extent to which estimated wage differentials vary across methods for measuring sexual orientation. We show

that using different methods leads to meaningfully different estimates of wage

differentials for lesbians.

Empirical Approach

We follow the existing literature on estimating wage differentials for lesbians,

but we also allow the wage differential to vary over time. We predict log hourly

wages,

ŵi = α + β1 Li + β2 Yit + β3 (Li ∗ Yit ) + βXi + i

(1)

where Li is a dummy variable taking a value of one if a female respondent

self-identifies as a lesbian or bisexual. Yit is a year fixed effect, and Li ∗ Yit is

an interaction term between “lesbian” and “year” that allows us to capture

differences in the wage differential over time. Xj is a vector of control variables

that includes measures of human capital (years of education and potential experience, its square, and interaction between lesbian and potential experience)

and demographics and family characteristics (race, marital status, number of

8

children, region of residence and residence in a metro area). Some specifications below also include interaction terms between lesbian sexual orientation

and characteristics such as potential experience and number of children.

Note that our dependent variable is the hourly wage. Hourly wage is not

recorded in the GSS, but we use the two-step procedure outlined elsewhere to

estimate it (Martell 2013a; Martell 2013b). We first estimate dollar amounts

for annual earnings within the categories reported in the GSS following Badgett’s (1995) approach, which is also the most common approach.6 For each

year of the GSS, we use that year’s Current Population Survey to compute the

median annual earnings within each earnings range for all women who work.

Medians are reported in 2010 dollars. This procedure allows the estimate of

earnings to vary across time within the fixed ranges used by the GSS. However,

for each point in time, variation is still limited, which increases the probability

of type two error (failing to detect wage differentials when they exist).

To compute hourly wage, we divide annual earnings by annual hours of

work. Annual hours is the number of hours the respondent worked last week,

as reported in the GSS, times 50 work-weeks. This hours information was

not available in many of the earlier versions of the GSS that also had sexual

behavior information. In our main specifications we restrict the estimation

sample to those reporting in the GSS that they work full-time. Full-time

workers reported a mean of 43 hours per week with a standard deviation of

10 hours. We also provide specifications with log(annual earnings) as the

dependent variable for comparability with earlier studies.

– Table 2 about here –

6

There have been several approaches to estimating earnings with the GSS. A straightforward approach is to use the midpoint of the income categories reported in the GSS. A

second approach that utilizes the categorical income information is to estimate the probability of being in one category relative to the others using maximum likelihood (Berg and Lien

2002). Findings using the GSS data from the 1990s were consistent regardless of measure

of income.

9

As noted above, because homosexual and bisexual orientation are relatively

rare, the number of lesbians in the GSS is small. Table 2 shows the number of

self-identified lesbians and bisexual women in the sample, along with descriptive statistics of the independent variables. The data include 38 self-identified

lesbian or bisexual women who work full-time, which is just over three percent of the population. This estimate is consistent with existing counts in the

demographic literature (Berg and Lien 2006). Combining lesbians and bisexuals in the data aligns our specifications with those in the existing literature

and creates a larger sample size for estimation. Self-identified lesbians are less

likely to be married, have fewer children, and are more likely to be white than

heterosexual women. We would normally expect these characteristics to be

associated with higher earnings for women. However, self-identified lesbians

have lower average hourly wages than heterosexual women. Annual earnings

of the two groups are not different.

Table 3 shows the estimated wage differentials for self-identified lesbians.

Specifications (1)-(3) show differentials in the hourly wage; specifications (4)(6) show differentials in annual earnings. The first two specifications in each

group of three include full-time workers only; specifications (3) and (6) include

both full-time and part-time workers. All specifications include controls for

census region, and specifications (2)-(3) and (5)-(6) add controls for occupation. All specifications also include an interaction between sexual orientation

and experience, which was suggested by Badgett (1995) and included in nearly

all studies. The interpretation of this coefficient is discussed at length below.

– Table 3 about here –

We find a large but statistically insignificant wage penalty for self-identified

lesbians who worked full-time in 2008. The wage penalty in 2008 is statisti-

10

cally significant when part-time workers are included.7 We find a larger and

statistically significant wage penalty in 2010 that is robust to the inclusion of

occupational controls. The wage penalty in 2010 is approximately 50 percent

of the mean wage, or $6.50 an hour.8 We estimate a wage penalty of just six

percent in 2012, but it is not statistically significant. We find a significant

difference in annual earnings only in 2008 and only when part-time workers

are included.9

Finding a lesbian wage penalty during a period when non-discrimination

laws have come to protect many lesbians and gay men, and when public opinion polls suggest that acceptance of same-sex marriage and child-rearing are

rising, presents a new puzzle for researchers. By 2008, the beginning of the period that our data span, nearly half of all states had implemented laws making

employment discrimination based on sexual orientation illegal (Martell 2013b).

While the passage of these laws had many causes, public support of protection from discrimination for gay and lesbian workers was an important factor

(Haider-Markel and Meier 1996; Klawitter 2011). Indeed, an increase in tolerance in states with non-discrimination laws (Martell 2013b) has been accompanied by increasing levels of tolerance of homosexuality across the country

(Smith 2011). To investigate this puzzle, we consider whether:

1. The penalty is the result of the use of self-identified sexual orientation

rather than researcher assignment to the lesbian group. Is there a measurable penalty for researcher-identified lesbians? Are the lesbians who

self-identify different in important ways from the people to whom re7

We also note that self-identified lesbians are more likely to be unemployed each survey

year. The largest difference was in 2008 when 11 percent of self-identified lesbian respondents

were unemployed in 2008 while only three percent of heterosexual women surveyed were

unemployed.

8

Marginal effects are calculated as eβ1 − 1.

9

Lesbians may be compensating for a lower hourly wage by working more (Klawitter

2011).

11

searchers assign homosexual orientation?

2. The penalty is a result of mis-specification of the model. Are there

important differences in returns to characteristics between lesbians and

heterosexuals, or changes in those returns over time, that eliminates the

penalty?

The Role of Researcher Assignment

We begin our investigation of the role of researcher assignment of sexual orientation by estimating wage differentials for researcher-identified lesbians for

comparison with the results in table 3. We consider two ways to identify

respondents as lesbian. We use the most common definition from the literature, which is to identify a respondent as lesbian if she had any same-sex sex

partners in the last five years. We also include a less-common definition: a

respondent is identified as lesbian if half of her sex partners since the age of

eighteen have been female. Previous research has also identified respondents

as lesbian if they have had at least one same-sex sex partner in the previous

year or at least once since the age of eighteen. We focus on the “last five years”

and “half of sex partners” definitions because they are most closely correlated

with self-identified sexual orientation in our data.

Table 4 shows that there were statistically significant and large wage and

earnings penalties for researcher-identified lesbians in 2008, regardless of definition or specification. On average, the penalty for researcher-identified lesbians

in 2008 is one-third larger than the largest statistically significant penalty

measured for self-identified lesbians. In 2010, however, researcher-identified

lesbians experienced a significant wage premium after controlling for occupation in specification (3). In 2012 we observe wage and earnings premia in five of

the six specifications. These results do not mirror the results for self-identified

12

lesbians in table 3, for whom there was a wage penalty for full-time workers in

all years, with the largest, statistically significant, and robust penalty found

in 2010. Identity and disclosure matter.

–Table 4 about here –

To investigate further the role of identity and disclosure, we consider women

who both self-identify as lesbians and are identified by researchers using the

“past five years” definition of sexual behavior. These results are shown in

the first and second columns of table 5. For the intersection of the sets of

self-identified and researcher-identified lesbians, we find a wage penalty for

lesbians in 2008, but it is statistically significant only when we include parttime workers in specification (2). We document a larger penalty for the union

of the sets, as shown in the third and fourth columns of table 5. We also find a

wage premium in 2012 for the union of researcher-identified and self-identified

lesbians. The results for the union of the sets appear to be dominated by

outcomes for researcher-identified lesbians, while the results for the intersection

of the sets (2) are similar, but not identical, to the results for self-identified

lesbians. Again we see that identity and disclosure matter in the estimation

of the wage differential.

–Table 5 about here –

A comparison of the descriptive statistics in tables 2 and 6 reveals that,

on average, self-identified lesbians are similar to women who are classified as

lesbian based upon their sexual behaviors. Self-identified lesbians are (unsurprisingly) less likely to be married. They have fewer children and have more

education. None of these differences is statistically significant.

– Table 6 about here –

However, a large proportion of respondents are misclassified: 20 percent of

self-identified lesbians would not be classified as lesbians on the basis of their

13

reported sexual behavior, and more than 30 percent of researcher-identified

lesbians do not self-identify. This misclassification is not surprising. Selfidentified sexual orientation, sexual desire and sexual behavior are distinct, and

each is the product of a complex social process (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael,

and Michaels 1994; Carpenter 2008).

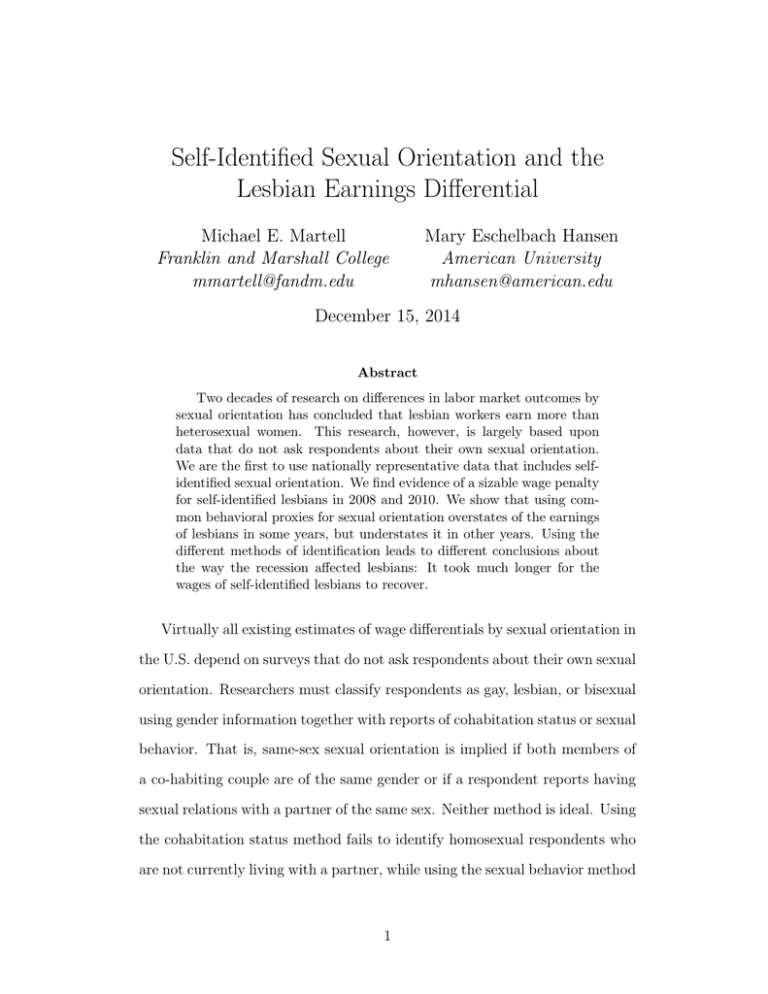

Consider first the women who engage in same-sex sexual behavior but who

not self-identify as lesbian or bisexual. Figure 1 compares the number and

characteristics of these women. Researcher-identified lesbians who do not also

self-identify have less education, less potential experience (are younger) and

have more children than respondents who self-identify but are not researcheridentified. Despite the small numbers, these differences are large enough to be

statistically significant at the 10 percent level. These differing characteristics

may play a role in explaining why we document different wage penalties for

self-identified and researcher-identified lesbians. Note also that this type of

misclassification is much less prominent for men in the GSS (Martell 2013a).

Now consider differences between the women who self-identify as lesbian

but who are not identified by researchers as lesbian. The age, education, and

child-bearing patterns for this group are not different from the intersection of

the sets when the “last five years” definition is used, but when the “half of partners” definition is used, these women are older, more education and have fewer

children than the group that both self-identifies and is researcher-identified.

There is an additional – and important – difference between women who selfidentify but are not researcher-identified. All researcher-identified lesbians are

sexually active, and sexually active women have higher earnings than sexually

abstinent women (Black, Markar, Sanders, and Taylor 2003). Not all selfidentified lesbians are sexually active. If respondents abstain from sex, they

do not receive this premium. Misclassification therefore introduces an impor-

14

tant bias, and we cannot rule out the possibility that mis-classification plays

a role in explaining the differences between our findings and earlier findings

using the GSS.

The Role of Returns to Characteristics

Though it would be desirable to use a full decomposition to investigate the

role of returns to characteristics, there are too few observations of lesbians to

obtain useful estimates. We instead check the robustness of the lesbian wage

penalty to a series of expanded specifications that include the interaction of

sexual orientation with human capital and the interaction of sexual orientation

with both family characteristics and year of observation.

We begin by considering whether lesbians earn the same returns to their

human capital, as measured by years of education and potential experience, as

heterosexual women. The expectation that lesbians have higher returns to experience than heterosexual women reaches back to Badgett (1995). She argued

that the typical proxy for potential experience (age minus five years) is more

accurate for lesbian women because they are less likely to bear children, and

therefore they are less likely to have interruptions in their careers. Excluding

the lesbian*experience interaction would therefore overestimate the earnings

of lesbians relative to heterosexual women. Jepsen (2007), Davenshary et al.

(2008), Klawitter (2011) and others make similar arguments. Klawitter (2011)

argues that labor market attachment explains much of the lesbian premium

she documents. In Jepsen (2007), the lesbian*experience interaction term is

smaller than previous estimates using earlier data, and including it considerably reduces the lesbian premium. In contrast, in our pooled GSS data,

the penalty remains when sexual orientation and experience are interacted, as

shown in tables 3 and 4. In table 7 we expand the specification to allow for

15

an interaction between lesbian sexual orientation and years of education. We

do not find a statistical difference.

–Table 7 about here –

Note that allowing the returns to education to vary between heterosexual

and lesbian women causes the statistical significance of the lesbian penalty in

2008 to fall below conventional levels for researcher-identified of lesbians, but

causes the estimated penalty to increase and become statistically significant

for both 2008 and 2010 for self-identified lesbians.

As we discuss more below, the small number of observations of lesbians

in many occupational groups limits our ability to pursue such an exercise.

However, the small sample does not detract from our primary point: Our

understanding of the history of employment outcomes for lesbians is quite

sensitive to the way lesbian workers are identified.

Table 8 shows that the divergence in patterns of changes in the wage differential by method of identification remains when we allow the “returns” to

family characteristics to differ both across groups of women (specifications (1)

and (3)) and over time (specifications (2) and (4)). We find no evidence of a

difference in the returns to marriage or children between lesbian and heterosexual women in any year (only base year shown). These results are consistent

with Jepsen (2007), who studies a period before the recent changes in laws regarding marriage equality and increases in the social acceptance of gay families

discussed above.10

– Table 8 about here –

We do, however, find a statistically significant marriage premium of about

10

Of course, marriage is a problematic variable for lesbians because they are still legally

denied access to marriage in many states. We are unable to observe in GSS data whether

lesbians who are cohabiting in marriage-like relationships identify as married. Further,

demographic research has found that a large portion of lesbians do not formally register

what would constitute a legally recognized relationship (Carpenter and Gates 2008).

16

seven percent for all women, while our estimate of the child penalty is not

statistically significant. While evidence on the impact of marriage on women’s

wages is mixed (Loughran and Zissimopoulos 2009), our estimate of the marriage premium for women is somewhat larger than the premium recently estimated by Killewald and Gough (2013).

Our failure to capture a motherhood penalty is not entirely consistent with

recent work that finds it to be approximately five percent (Budig and Hodges

2010). However, we note that the impact of motherhood on wages is heterogeneous: Lower-earning women experience a larger penalty than higher-earning

women, and there is evidence of a motherhood premium among highly educated women (Amuedo-Dorantes and Kimmel 2005). The difference between

our results and most may therefore be an artifact of either the co-incidence

of the sample frame with the recession and recovery, of our inability to use a

fully interacted model, or of including only full-time workers in our regressions.

In particular, including only full-time workers is likely to under-estimate the

motherhood penalty because mothers who expect large wage penalties are less

likely to work full-time (Budig and England 2001).

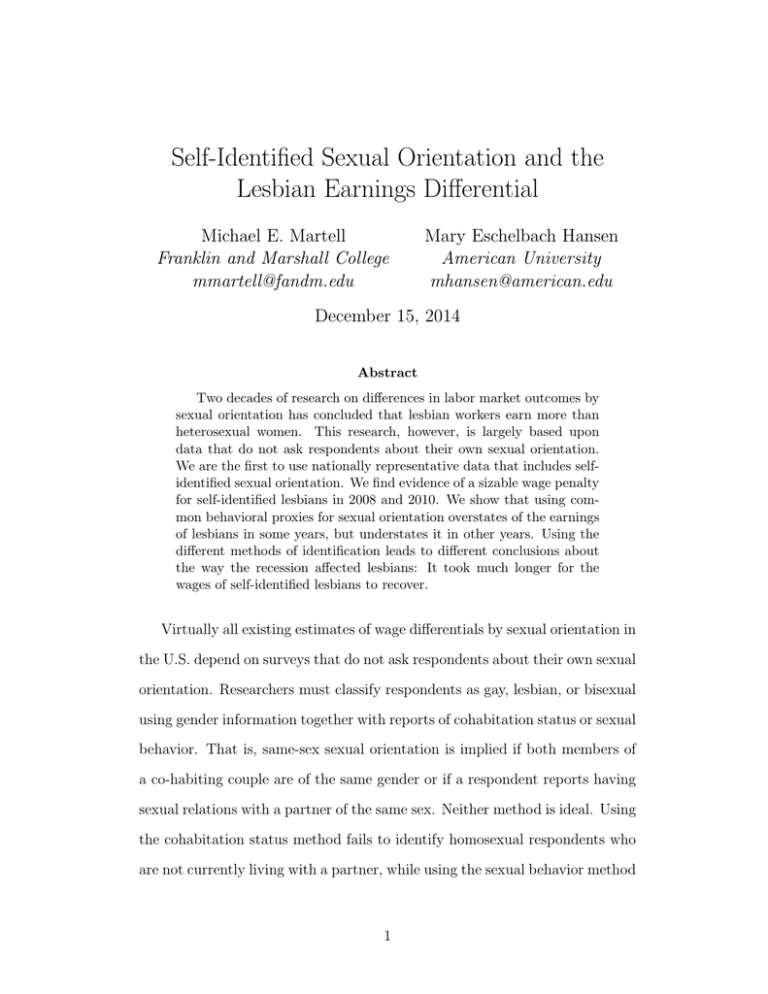

Changes in the wage differential across regions have the potential to drive

patterns in the lesbian wage premium. Legal recognition of same-sex marriage,

increased legal opportunities for lesbian and gay men to adopt children, and

protection from discrimination (ENDAs) have increased fairly quickly, but not

evenly across the U.S., as shown in Figure 2. In particular, the legal equality

movement has proceeded more quickly in the West, Northeast and northern

Midwest than it has in other regions. In table 9 we allow the lesbian wage

differential to vary with region and across years. The interactions eliminate

the statistical significance of the penalty for both self-identified and researcheridentified lesbians (specifications (1) and (2)) and increase the point estimates

17

of the premium for researcher-identified lesbians in 2012. Again, including the

interactions does not eliminate the divergence in patterns over time between

lesbians identified by the two different methods.

– Table 9 and Figure 2 about here –

Finally, we investigate the impact of occupational choices and the distribution of wages across occupations by allowing the returns to occupations to vary

with sexual orientation and across years. We group respondents into broad

occupational categories.11 As tables 2 and 6 show, there are small numbers of

lesbians in some occupations. Many year-occupation cells are empty. Therefore, these results should be interpreted cautiously. Specification (2) of table

10 shows that the penalty for self-identified lesbians in 2010 is robust to allowing the returns to occupation to vary by sexual orientation. When we allow

the returns to occupation to vary by sexual orientation and year, we find a

penalty in 2008 but a premium for self-identified lesbians 2010 and 2012 (specification 2). This is the only specification in which results for self-identified

lesbians converge to the results for researcher-identified lesbians.

–Table 10 about here –

The biggest difference in occupations between heterosexual and lesbian

women (regardless of method of identification) is the over-representation of

lesbians among managers and supervisors. Of course, this difference may simply be a side effect of the higher returns to experience. Then again, it could be

an artifact of an unobserved difference in personality characteristics or workplace behaviors.

11

Occupations include: Managers & Supervisors, Professional, Teaching/Social Work,

Allied Health, Support, Sales, Personal Service, Agricultural, Construction & Technology,

and Laborer. These categories are based on the 2010 Standard Occupational Classification

codes of the U.S. Census.

18

The Role of Employment Status

While a full accounting of the causes of differing patterns over time in the

experiences of self-identified and researcher-identified lesbians is beyond the

scope of the current paper, we show in table 11 that the difference in patterns in

wages is related to differences in employment status across years. We estimate

by multinomial logit:

ŷi = β1 Li + β2 Yit + β3 (Li ∗ Yit ) + βXi + i

(2)

where yi equals 0 if respondents are not working, 1 if working part-time

and 2 if working full-time. All variables are defined as in previous sections,

and we add a proxy for non-labor income in Xi .12 Table 11 presents marginal

effects calculated at the mean for each outcome of the dependent variable.

Researcher-identified lesbians experienced the same relatively good employment outcomes as heterosexual women during the recession (see, for example,

Hartmann 2010). There were no significant differences between researcheridentified lesbians and heterosexuals in the propensity to work full or part-time

in any year. In contrast, self-identified lesbians were approximately 27 percent

less likely to work full-time and 16 percent more likely to work part-time in

2008 than heterosexual women.

–Table 11 about here–

The differences in the work status regressions are consistent with the timing

of the differences in wage differentials because the wage/income measure in the

GSS is retrospective – it refers to income for past year – while work status

question refers to the past week. If self-identified lesbians worked less in 2008

and 2009, their lower incomes and hourly wages are captured in the 2010

12

Non-labor income is proxied as total income minus respondent’s income, which is the

same proxy utilized in (Martell 2014).

19

survey. These underemployed workers may have been more likely to change

jobs in 2008 and 2009, and were also likely to have been among those most

burdened by the recession (Biddle and Hammermesh 2013; Elsby, Shin, and

Solon 2013).

The signs and significance of the marginal effects of control variables (presence of children, education and marriage) are consistent with the existing literature. This pattern is robust to including interactions for marriage and

children, but interacting lesbian and education removes the significance of the

marginal effect of the recession on work status for all classification techniques

(not shown).13

There are not enough observations of lesbians in the GSS to to solve the

puzzle of the emerging lesbian wage puzzle completely. We have shown that

the lesbian wage penalty is robust to a variety of empirical specifications and

likely related to varying employment patterns between heterosexual and lesbian women. However, the GSS does not have enough observations to fully

investigate the occupational attainment of lesbians or the source of the disproportionate impact of the recession on lesbians. It is clear, however, that

the size and persistence of the lesbian wage differential depends upon whether

a lesbian claims the label herself or whether it is assigned to her by the researcher.

Conclusion

This paper makes two contributions to the literature on the earnings differentials between lesbians and heterosexual women. First, while the bulk of

13

When we include the lesbian*occupation interaction self-idenified and researcheridentified lesbians are both more likely to be unemployed and less likely to work full time

in 2008. The convergence of estimates only occurs with the occupation interactions, which

mirrors the results for wage differentials.

20

the existing literature finds a lesbian premium, we find evidence of a lesbian

wage penalty of roughly 50 percent for self-identified lesbians in 2010, and

an even larger penalty for researcher-identified lesbians in 2008. We know

little about the experience of gays and lesbians in economic downturns, but

finding of a lesbian penalty in any recent year using any method of identification is surprising given changes in public opinion and the expansion of

non-discrimination laws. The GSS data suggest that self-identified lesbians

were hit harder by the recession than other groups, but the results are not

conclusive. As more data become available, future research should investigate

the mechanism through which the disadvantage manifested during the recession. In particular, it should investigate selection into occupations and into

parenthood for lesbians.

More fundamentally, we show that the method of identifying lesbians is

important for the measurement of wage differentials. The shortcomings of

behavioral definitions of lesbians and of the use cohabitation based data are

well known. The existing literature acknowledges that cohabitation based

data excludes single lesbians and that selection into marriage like relationships

varies by sexual orientation (Carpenter and Gates 2008). However, to our

knowledge, we are the first to demonstrate that mis-classification matters to

our understanding of the history of labor market outcomes for homosexuals.

21

22

GSS 1989-1991

GSS & 1992 NHSLS*

GSS 1989-1996

GSS 1989-1996

GSS 1991-1996

GSS 1994-2002

GSS 1988-2006

1990 U.S. Census

1990 U.S. Census

2000 U.S. Census (state of MA only)

2000 U.S. Census

2000 U.S. Census

2000 Census

2000 Census

2000 Census

2000 Census

2000 Census

2004 CPS

BRFSS 1996-2000**

CHIS 2001*** and GSS

Badget (1995)

Badgett (2001)

Blandford (2003)

Black et al. (2003)

Berg and Lien (2002)

Comolli (2005)

Cushing-Daniels and Yeung (2009)

Klawitter and Flatt (1998)

Clain and Leppel (2001)

Albelda et al. (2005)

Gates (2009)

Antecol et al. (2007)

Daneshevary, Waddoups, and Wimmer (2008)

Daneshevary, Waddoups and Wimmer (2009)

Klawitter (2011)

Baumle and Poston (2011)

Jepsen (2007)

Elmslie and Tebaldi (2007)

Carpenter (2004)

Carpenter (2005)

Sexual Behavior

Sexual Behavior

Sexual Behavior

Sexual Behavior

Sexual Behavior

Sexual Behavior

Sexual Behavior

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Cohabitation Status

Self-reported

Self-reported and Sexual Behavior

Method of ID

Insignificant premium

Insignificant premium

Premium

Premium

Premium

Premium

Insignificant penalty

Premium, but household penalty

Premium

Premium

Premium

Premium

Premium, gap higher with less education

Wages of never-married lesbians highest

Premium

Premium

Premium

Insignificant premium

Household income penalty

Insignificant penalty

Findings for Lesbians

Notes: * National Health and Nutrition Survey, **Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, ***California Health Interview Survey.

Data

Study

Table 1: Studies of lesbian wage and income differentials in the U.S. by data source.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for self-identified lesbians.

Self-Identified

Lesbian

Mean St. Dev.

2.58

1.11

10.26

1.03

Log(Wages)

Log(Earnings)

Heterosexual

Mean St. Dev.

2.62

0.81

10.27

0.82

Years of Educ.

Potential Exp.

Married

Num. Children

White

Metro

14.97

20.16

0.18

0.82

0.84

0.21

2.69

10.42

0.39

0.93

0.37

0.41

14.26

24.02

0.45

1.64

0.75

0.15

2.89

12.87

0.50

1.43

0.43

0.36

Occupation

Man & Sup

Professional

Teach/Soc Wok

Allied Health

Support

Sales

Pers Svc

Ag

Constr & Tech

Laborer

Total

N

13

5

2

6

5

1

4

0

1

1

38

Percent

0.34

0.13

0.05

0.16

0.13

0.03

0.11

0.00

0.03

0.03

1.00

N

221

107

120

117

204

78

123

5

9

76

1,060

Percent

0.21

0.10

0.11

0.11

0.19

0.07

0.12

0.00

0.01

0.07

1.00

Region

New England

Mid Atlantic

E. No. Central

W. No. Central

So. Atlantic

E. So. Central

W. So. Central

Mountain

Pacific

Total

N

2

5

5

2

10

1

4

7

2

38

Percent

0.05

0.13

0.13

0.05

0.26

0.03

0.11

0.18

0.05

1.00

N

49

147

165

81

235

68

104

80

131

1,060

Percent

0.05

0.14

0.16

0.08

0.22

0.06

0.10

0.08

0.12

1.00

Note: Full-time workers only.

23

24

(2)

SID

Log(W )

−0.349

(0.350)

−0.505∗

(0.300)

−0.040

(0.284)

0.048∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.023∗∗

(0.011)

−0.026

(0.050)

−0.013

(0.049)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.399

(3)

SID

Log(W )

−0.607∗

(0.333)

0.027

(0.309)

0.392

(0.331)

0.038∗∗∗

(0.006)

0.018∗

(0.010)

−0.021

(0.048)

0.024

(0.048)

Y es

Y es

1438

0.317

(4)

SID

Log(E)

−0.325

(0.297)

−0.343

(0.257)

0.059

(0.222)

0.058∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.021∗∗

(0.009)

−0.041

(0.051)

−0.044

(0.050)

Y es

No

1098

0.370

(5)

SID

Log(E)

−0.339

(0.305)

−0.344

(0.263)

0.110

(0.242)

0.054∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.018∗

(0.009)

−0.001

(0.048)

0.011

(0.047)

Y es

Y es

1098

0.442

(6)

SID

Log(E)

−0.543∗∗

(0.265)

0.006

(0.256)

0.327

(0.262)

0.062∗∗∗

(0.005)

0.017∗∗

(0.008)

−0.035

(0.049)

−0.036

(0.048)

Y es

Y es

1754

0.360

Note: Specification follows Badgett (1995). Full-time workers only in Columns 1, 2, 4, and 5. Full-time and part-time workers in

columns 3 and 6. All specifications include a squared term in experience and controls for years of education, race, marital status and

residence in a large metro area. Robust standard errors in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant at 5 % *** Significant at

1 %.

Regions

Occupations

Observations

R2

Year = 2012

Year = 2010

Lesbian*Exp

Experience

Lesbian*2012

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian

(1)

SID

Log(W )

−0.296

(0.332)

−0.529∗

(0.287)

−0.062

(0.260)

0.051∗∗∗

(0.008)

0.024∗∗

(0.011)

−0.060

(0.052)

−0.065

(0.050)

Y es

No

1093

0.344

Table 3: Penalty for self-identified lesbians in pooled GSS sample.

25

(2)

RID 5Y

Log(W )

−0.804∗∗∗

(0.288)

0.514∗

(0.292)

0.913∗∗∗

(0.268)

0.038∗∗∗

(0.006)

0.013

(0.009)

−0.045

(0.048)

0.002

(0.048)

Y es

Y es

1438

0.321

(3)

RID 5Y

Log(E)

−0.715∗∗

(0.292)

0.293

(0.266)

0.610∗∗∗

(0.237)

0.053∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.017∗∗

(0.008)

−0.029

(0.047)

−0.009

(0.047)

Y es

Y es

1098

0.443

(4)

RID Half

Log(W )

−0.760∗∗

(0.313)

0.038

(0.347)

0.389∗

(0.224)

0.047∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.023

(0.014)

−0.048

(0.050)

−0.018

(0.049)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.395

(5)

RID Half

Log(W )

−0.772∗∗

(0.322)

0.332

(0.363)

0.716∗

(0.380)

0.039∗∗∗

(0.006)

0.017

(0.012)

−0.028

(0.049)

0.028

(0.048)

Y es

Y es

1438

0.316

(6)

RID Half

Log(E)

−0.469

(0.323)

−0.084

(0.384)

0.136

(0.270)

0.054∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.017

(0.015)

−0.014

(0.047)

0.013

(0.047)

Y es

Y es

1098

0.439

Note: Specification follows Badgett (1995). Full-time workers only in columns 1, 3, 4 and 6. Full-time and part-time workers in

columns 2 and 4. All specifications include a squared term in experience and controls for years of education, race, marital status and

residence in a large metro area. Robust standard errors in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant at 5 % *** Significant at

1 %.

Regions

Occupations

Observations

R2

Year = 2012

Year = 2010

Lesbian*Exp

Experience

Lesbian*2012

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian

(1)

RID 5Y

Log(W )

−0.720∗∗

(0.334)

0.147

(0.300)

0.606∗∗

(0.268)

0.046∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.019∗∗

(0.009)

−0.054

(0.049)

−0.037

(0.049)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.399

Table 4: Penalty for researcher-identified lesbians in pooled GSS sample.

Table 5: Penalty for intersection and union of self-identified and researcheridentified groups.

Lesbian

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian*2012

Experience

Lesbian*Exp

Year = 2010

Year = 2012

Regions

Occupations

Observations

R2

(1)

Both

Log(W )

−0.543

(0.385)

−0.301

(0.312)

0.229

(0.314)

0.047∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.024∗∗

(0.011)

−0.034

(0.050)

−0.018

(0.049)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.398

(2)

Both

Log(W )

−0.761∗∗

(0.353)

0.216

(0.343)

0.819∗∗

(0.340)

0.038∗∗∗

(0.006)

0.018

(0.011)

−0.027

(0.048)

0.017

(0.048)

Y es

Y es

1438

0.318

(3)

Either

Log(W )

−0.570∗

(0.321)

−0.048

(0.293)

0.384

(0.258)

0.047∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.019∗∗

(0.009)

−0.046

(0.049)

−0.032

(0.049)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.398

(4)

Either

Log(W )

−0.677∗∗

(0.280)

0.330

(0.271)

0.599∗∗∗

(0.267)

0.038∗∗∗

(0.006)

0.014

(0.008)

−0.039

(0.048)

0.010

(0.049)

Y es

Y es

1438

0.318

Note: Specification follows Badgett (1995). First specification in each pair includes full-time workers only; second specification includes full-time and parttime workers. All specifications include a squared term in experience and controls

for years of education, race, marital status and residence in a large metro area.

Robust standard errors in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant at 5

% *** Significant at 1 %.

26

27

N

15

4

4

8

4

3

6

0

1

2

47

N

Occupation

Man & Sup

Professional

Teach/Soc Wok

Allied Health

Support

Sales

Pers Svc

Ag

Constr & Tech

Laborer

Total

Region

New England

Mid Atlantic

E. No. Central

W. No. Central

So. Atlantic

E. So. Central

W. So. Central

Mountain

Pacific

Total

1

5

5

1

14

2

6

6

7

47

14.28

19.26

0.21

0.98

0.87

0.15

Years of Educ.

Potential Exp.

Married

Num. Children

White

Metro

Log(Wages)

Log(Earnings)

Percent

0.02

0.11

0.11

0.02

0.30

0.04

0.13

0.13

0.15

1.00

Percent

0.32

0.09

0.09

0.17

0.09

0.06

0.13

0.00

0.02

0.04

1.00

2.47

11.15

0.41

1.11

0.34

0.36

Lesbian

Mean St. Dev.

2.46

1.03

10.13

1.00

Percent

0.05

0.14

0.16

0.08

0.22

0.06

0.10

0.08

0.12

1.00

Percent

0.21

0.10

0.11

0.11

0.20

0.07

0.12

0.00

0.01

0.07

1.00

2.90

12.84

0.50

1.43

0.44

0.36

0

3

4

0

6

1

1

2

3

20

N

6

2

3

1

2

2

1

0

0

3

20

N

14.90

20.25

0.10

0.90

0.80

0.20

Percent

0.00

0.15

0.20

0.00

0.30

0.05

0.05

0.10

0.15

1.00

Percent

0.30

0.10

0.15

0.05

0.10

0.10

0.05

0.00

0.00

0.15

1.00

2.92

11.35

0.31

0.97

0.41

0.41

N

51

149

166

83

239

68

107

85

130

1,078

N

228

110

119

122

207

77

126

5

10

74

1,078

14.27

23.95

0.45

1.63

0.75

0.15

Percent

0.05

0.14

0.15

0.08

0.22

0.06

0.10

0.08

0.12

1.00

Percent

0.21

0.10

0.11

0.11

0.19

0.07

0.12

0.00

0.01

0.07

1.00

2.88

12.83

0.50

1.43

0.43

0.36

Heterosexual

Mean St. Dev.

2.63

0.81

10.28

0.82

Researcher-Identified (5Y)

Lesbian

Mean St. Dev.

2.48

1.18

10.19

1.17

Note: Full-time workers only.

N

50

147

165

82

231

67

102

81

126

1,051

N

219

108

118

115

205

76

121

5

9

75

1,051

14.28

24.09

0.45

1.64

0.75

0.15

Heterosexual

Mean St. Dev.

2.63

0.81

10.28

0.82

Researcher-Identified (5Y)

Table 6: Descriptive statistics for researcher-identified lesbians.

Table 7: Changes in the lesbian wage differential from 2008-2012, allowing

returns to experience and education to interact with sexual orientation.

(1)

SID

Lesbian

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian*2012

Experience

Lesbian*Exp

Years Education

Lesbian*Educ

Regions

Occupations

Observations

R2

−1.040∗

(0.621)

−0.539∗

(0.294)

−0.054

(0.272)

0.048∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.019∗

(0.011)

0.109∗∗∗

(0.010)

0.052

(0.040)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.400

(2)

RID 5Y

−0.707

(0.615)

0.148

(0.314)

0.605∗∗

(0.267)

0.046∗∗∗

(0.007)

0.020∗∗

(0.010)

0.110∗∗∗

(0.010)

−0.001

(0.047)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.399

Note: Full-time workers only. All specifications include a squared term in experience and controls for years of education, race, and residence in a large metro

area. Robust standard errors in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant

at 5 % *** Significant at 1 %.

28

Table 8: Changes in the lesbian wage differential from 2008-2012, allowing

returns to family characteristics to interact with sexual orientation.

Lesbian

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian*2012

Children

Lesbian*Children

Married

Lesbian*Married

Regions

Occupations

Observations

R2

(1)

SID

(2)

SID

−0.330

(0.366)

−0.477∗

(0.283)

−0.151

(0.306)

−0.017

(0.016)

−0.184

(0.152)

0.073∗

(0.041)

0.364

(0.406)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.401

−0.223

(0.472)

−0.526

(0.624)

−0.511

(0.555)

−0.017

(0.016)

−0.361

(0.372)

0.073∗

(0.041)

0.635

(0.510)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.404

(3)

RID 5Y

(4)

RID 5Y

−0.790∗∗

(0.369)

0.170

(0.316)

0.609∗∗

(0.266)

−0.020

(0.016)

0.048

(0.101)

0.073∗

(0.042)

0.244

(0.319)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.400

−0.983∗∗

(0.469)

0.363

(0.501)

0.717

(0.444)

−0.020

(0.016)

0.158

(0.209)

0.072∗

(0.042)

0.311

(0.689)

Y es

Y es

1093

0.402

Note: Full-time workers only. All specifications include a squared term in experience and controls for years of education, race, and residence in a large metro

area. Robust standard errors in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant

at 5 % *** Significant at 1 %.

29

Table 9: Changes in the lesbian wage differential from 2008-2012, allowing

returns to region to interact with sexual orientation.

Lesbian

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian*2012

Regions

Lesbian* Region

Lesbian*Reg*Year

Occupations

Observations

R2

(1)

SID

(2)

SID

−0.187

(0.280)

−0.083

(0.263)

0.092

(0.296)

Y es

Y es

No

Y es

1093

0.404

−0.041

(0.191)

−1.009

(0.729)

−0.393

(0.281)

Y es

Y es

Y es

Y es

1093

0.407

(3)

RID 5Y

(4)

RID 5Y

0.010

(0.167)

0.348

(0.289)

0.555∗∗∗

(0.258)

Y es

Y es

No

Y es

1093

0.405

−0.019

(0.173)

0.945∗∗∗

(0.273)

1.590∗∗∗

(0.500)

Y es

Y es

Y es

Y es

1093

0.408

Note: Full-time workers only. All specifications include a squared term in experience and controls for years of education, race, and residence in a large metro

area. Robust standard errors in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant

at 5 % *** Significant at 1 %.

30

Table 10: Changes in the lesbian wage differential from 2008-2012, allowing

returns to occupation to interact with sexual orientation.

(1)

SID

Lesbian

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian*2012

Regions

Occupations

Occ*Lesbian

Occ*Lesbian*Year

Observations

R2

−0.267

(0.364)

−0.486∗

(0.317)

−0.028

(0.288)

Y es

Y es

Y es

No

1093

0.404

(2)

SID

−0.795∗∗∗

(0.279)

0.290∗

(0.180)

0.567∗∗∗

(0.159)

Y es

Y es

Y es

Y es

1093

0.409

(3)

RID 5Y

(4)

RID 5Y

−0.716∗∗∗

(0.282)

0.043

(0.258)

0.527∗∗

(0.287)

Y es

Y es

Y es

Y es

1093

0.404

−0.502∗∗∗

(0.211)

0.283∗∗

(0.146)

0.441∗∗∗

(0.125)

Y es

Y es

Y es

No

1093

0.415

Note: Full-time workers only. All specifications include a squared term in experience and controls for years of education, race, and residence in a large metro

area. Robust standard errors in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant

at 5 % *** Significant at 1 %.

31

32

0.112

(0.108)

0.019

(0.112)

0.703

(27.771)

−0.004

(0.004)

−0.010∗∗∗

(0.002)

−0.029

(0.024)

−0.022

(0.025)

1742

0.158∗

(0.094)

−0.096

(0.096)

−1.960

(91.930)

−0.002

(0.004)

−0.013∗∗∗

(0.002)

0.015

(0.022)

0.005

(0.022)

1742

(2)

SID

Part-Time

−0.269∗∗

(0.133)

0.077

(0.132)

1.257

(64.159)

0.006

(0.005)

0.023∗∗∗

(0.003)

0.014

(0.027)

0.017

(0.028)

1742

(3)

SID

Full-Time

0.116

(0.102)

0.010

(0.119)

0.736

(26.443)

−0.010∗

(0.006)

−0.009∗∗∗

(0.002)

−0.027

(0.024)

−0.024

(0.025)

1742

(4)

RID 5Y

Unemployed

0.002

(0.089)

0.044

(0.094)

−1.885

(88.123)

0.003

(0.004)

−0.013∗∗∗

(0.002)

0.008

(0.022)

0.002

(0.022)

1742

(5)

RID 5Y

Part-Time

−0.118

(0.121)

−0.054

(0.131)

1.149

(61.680)

0.007

(0.005)

0.023∗∗∗

(0.003)

0.019

(0.027)

0.021

(0.028)

1742

(6)

RID 5Y

Full-Time

Note: Table shows estimated marginal effects from a multinomial regression. All specifications include a squared term in

experience and controls for years of education, race, residence in a large metro area and non-labor income. Standard errors

in parantheses. * Significant at 10 % ** Significant at 5 % *** Significant at 1 %.

Observations

Year = 2012

Year = 2010

Experience

Lesbian*Exp

Lesbian*2012

Lesbian*2010

Lesbian

(1)

SID

Unemployed

Table 11: Work status of self-Identified and researche-identified lesbians.

When RID defined as homosexual behavior in last 5 years

n=16, 2.4 years younger,

0.4 more children, less

likely married, 3 years

less ed

n=31

n=7

SID not RID

RID not SID

Both RID & SID

When RID defined as half of adult partners of same sex

n=25, 0.9 years older, 0.6

fewer children, 0.9 years

more ed

n=13

n=7

RID not SID

Both RID & SID

SID not RID

Figure 1: Comparing groups of self-identified and researcher-identified lesbians. Differences noted are statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

33

Figure 2: Summary of state laws on non-discrimination in employment, housing, and insurance, as well as marriage legality/recognition and adoption.

Source: Movement Advancement Project (2014).

34

References

Ahmed, A. M., L. Andersson, and M. Hammarstedt (2011). Inter- and

intra-household earnings differentials among homosexual and heterosexual couples. British Journal of Industrial Relations 49 (2), 248–278.

Ahmed, A. M., L. Andersson, and M. Hammarstedt (2013). Sexual orientation and full-time monthly earnings, by public and private sector:

Evidence from Swedish register data. Review of Economics of the Household 11 (1), 83–108.

Ahmed, A. M. and M. Hammarstedt (2010). Sexual orientation and earnings: a register data-based approach to identify homosexuals. Journal of

Population Economics 23 (3), 835–849.

Albelda, R., M. Ash, and M. Badgett (2005). Now that we do: Same-sex couples and marriage in Massachusetts. Massachusetts Benchmarks 7 (2),

16–24.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. and J. Kimmel (2005). The motherhood wage gap

for women in the United States: The importance of college and fertility

delay. Review of Economics of the Household 3 (1), 17–48.

Antecol, H., A. Jong, and M. Steinberger (2008). The sexual orientation

wage gap: The role of occupational sorting, human capital and discrimination. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 61 (4), 518–543.

Arabsheibani, G., A. Marin, and J. Wadsworth (2004). In the pink:

Homosexual-heterosexual wage differentials in the U.K. International

Journal of Manpower 25 (3), 343–354.

Badgett, M. (1995). The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination.

Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (3), 726–739.

Badgett, M. (2001). Money, Myths and Change: The Economic Lives of

Lesbians and Gay Men. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baumle, A. K. and D. L. Poston (2011). The economic cost of homosexuality:

Multilevel analyses. Social Forces 89 (3), 1005–1031.

Becker, G. (1957). The Economics of Discrimination. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Berg, N. and D. Lien (2002). Measuring the effect of sexual orientation on

income: Evidence of discrimination? Contemporary Economic Policy 4,

394–414.

Berg, N. and D. Lien (2006). Same-sex sexual behavior: U.S. frequency

estimates from survey data with simultaneous misreporting and nonresponse. Applied Economics 38 (7), 757–769.

Biddle, J. E. and D. S. Hammermesh (2013). Wage discrimination over the

business cycle. IZA Journal of Labor Policy 2 (7).

35

Black, D., H. Markar, S. Sanders, and L. Taylor (2003). The earnings effeccts

of sexual orientation. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56 (3), 53–

70.

Black, D., S. Sanders, and L. Taylor (2007). The economics of lesbian and

gay families. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (2), 53–70.

Blandford, J. (2003). The nexus of sexual orientation and gender in the

determination of earnings. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56 (4),

622–642.

Budig, M. J. and P. England (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood.

American Sociological Review 66 (2), 204–225.

Budig, M. J. and M. J. Hodges (2010). Differences in disadvantage: Variation in the motherhood penalty across white women’s earnings distribution. American Sociological Review 75 (5), 1–24.

Carpenter, C. S. (2004). New evidence on gay and lesbian household incomes. Contemporary Economic Policy 22 (1), 78–94.

Carpenter, C. S. (2005). Self-reported sexual orientation and earnings: Evidence from California. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 58 (2),

258–273.

Carpenter, C. S. (2008). Sexual orientation, work, and income in Canada.

Canadian Journal of Economics 41 (4), 1239–1261.

Carpenter, C. S. and G. Gates (2008). Gay and lesbian partnership: Evidence from California. Demography 45 (3), 573–590.

Clain, S. H. and K. Leppel (2001). An investigation into sexual orientation discrimination as an explanation for wage differences. Applied Economics 33, 37–47.

Clarke, G. and P. Sevak (2013). The disappearing gay income penalty. Economics Letters 121, 542–545.

Comolli, R. (2005). The Economics of Sexual Orientation and Racial Perception. Ph. D. thesis, Yale University.

Cushing-Daniels, B. and T.-Y. Yeung (2009). Wage penalties and sexual

orientation: An update using the General Social Survey. Contemporary

Economic Policy 27 (2), 164–175.

Daneshvary, N., C. Waddoups, and B. S. Wimmer (2008). Educational attainment and the lesbian wage premium. Journal of Labor Research 29,

365–379.

Daneshvary, N., C. Waddoups, and B. S. Wimmer (2009). Previous marriage

and the lesbian wage premium. Industrial Relations 48 (3), 432–453.

Drydakis, N. (2014). Sexual orientation discrimination in the Cypriot

labour market. distastes or uncertainty? International Journal of Manpower 35 (5), 720–744.

36

Elsby, M. W., D. Shin, and G. Solon (2013). Wage adjustment in the great

recession. NBER Working Paper (19478).

Gates, G. J. (2009). The impact of sexual orientation anti-discrimination

policies on the wages of lesbians and gay men. California Center for

Population Research Working Papers Series.

Haider-Markel, D. P. and K. J. Meier (1996). The politics of gay and lesbian rights: Expanding the scope of the conflict. The Journal of Politics 58 (2), 332–349.

Hartmann, H. I., A. English, and J. Hayes (2010). Women and men’s

employment and unemployment in the Great Recession. Institute for

Women’s Policy Research.

Jepsen, L. K. (2007). Comparing the earnings of cohabiting lesbians, cohabiting heterosexual women, and married women: Evidence from the 2000

Census. Industrial Relations 46 (4), 699–727.

Killewald, A. and M. Gough (2013). Does specialization explain marriage

penalties and premiums? American Sociological Review 78 (3), 477–502.

Klawitter, M. (2011). Multilevel analysis of the effects of antidiscrimination

policies on earnings by sexual orientation. Journal of Policy Analysis

and Management 30 (2), 334–358.

Klawitter, M. and V. Flatt (1998). The effects of state and local antidiscrimination policies on earnings for gays and lesbians. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 4, 658–686.

Laumann, E. O., J. H. Gagnon, R. T. Michael, and S. Michaels (1994). The

Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States.

The University of Chicago Press.

Loughran, D. S. and J. M. Zissimopoulos (2009). Why wait? The effect of

marriage and childbearing on the wages of men and women. Journal of

Human Resources 44 (2), 326–349.

Martell, M. E. (2013a). Differences do not matter: exploring the wage gap

for same-sex behaving men. Eastern Economic Journal 39 (1), 45–71.

Martell, M. E. (2013b). Do ENDAs end discrimination for behaviorally gay

men? Journal of Labor Research 34 (2), 147–169.

Martell, M. E. (2014). How ENDAs extend the workweek: Legal protection

and the labor supply of behaviorally gay men. Contemporary Economic

Policy 32 (3), 560–577.

Movement Advancement Project (2014). Snapshot: LGBT legal equality by

state. Date Accessed: November 10, 2014.

Peplau, L. A. (2003). Human sexuality: How do men and women differ?

Current Directions in Psychological Science 12 (2), 37–40.

37

Plug, E. and P. Berkhout (2008). Sexual orientation, disclosure and earnings.

IZA Discussion Paper (3290).

Smith, T. (2011). Public attitudes toward homosexuality. National Opinion

Reserach Council Technical Report.

Tebaldi, E. and B. Elmslie (2007). Sexual orientation and labor market

discrimination. Journal of Labor Research 28 (3), 436–453.

38