Department of Economics Working Paper Series Trade Agreements and Enforcement:

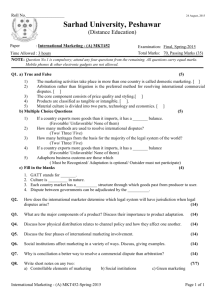

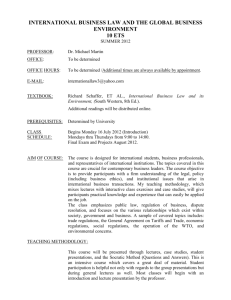

advertisement