An Overview of the Academic Research in Web Accessibility

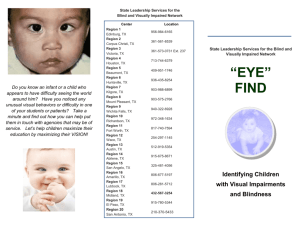

advertisement

An Overview of the Academic Research in Web Accessibility for the Visually Impaired Dena Al-Thani Researcher at Queen Mary University of London Open consultation meeting of the ITU Council Working Group on international internet-related public policy issues Topic: Access to the Internet for Persons with Disabilities and specific needs. Date: 15 February 2016 Email: d.al-thani@qmul.ac.uk Outline • Challenges facing visually impaired web users • An overview of the academic research work toward web accessibility for visually impaired • Challenges facing the current situation: the academic research work toward web accessibility for visually impaired • Quick overview of our work Challenges facing visually impaired web users • Accessibility of webpage contents • Compatibility web agents such as web browsers and media players • Compatibility of assistive technology tools with web technologies • Most importantly, the rapid growth of Web 2.0 technologies (where the user can also be the content creator). Issues persist in below mentioned technologies: 1. Screen readers don’t usually report dynamic changes in web content. 2. PDF documents are not always designed by their authors to be compatible with screen readers. The current situation: An overview of the academic research work toward web accessibility for visually impaired • User behavioural studies. Examples: • Dr Simon Harper and team from Manchester University reported user behaviour studies on visually impaired interaction in the web. (e.g. (Harper et al., 2013) and (Lunn et al., 2011) • Browser-specific solutions. Examples: • Non-visual Browsers: HearSay (Borodin et al., 2007) and CSurf (Mahmud et al., 2007) • Interface-specific solutions. Examples: • Enhanced website navigation using sound (Susini et al. (2002)): Borodin et al. (2008) proposed Dynamo, a simple and intuitive interface, through which changes that have occurred on a page can be reviewed. • Providing overviews of webpages (Murphy et al., 2007) • Audio supported search engines (Sahib et al., 2015): Google search engine need work to make them accessible. • Transcoding and Annotation. Examples: • Semantically enhanced voice web browser, SeEBrowser (Salampasis, 2005), was implemented which used ontologies to annotate web pages to semantically enhance browsing. • Concepts • Universal design (Shneiderman, 2000) • User-sensitive Inclusive design (Newell et. al, 2011 ) • Contextual design (Sloan et al., 2006) Challenges facing the current situation: the academic research working toward web accessibility for visually impaired • Website compliance with accessibility guidelines • Brown et al. (2012) reported the capability of screen readers used by VI participants who described their experience of browsing a set of ten web pages; none of these pages catered for the use of WAI-ARIA. • Awareness and knowledge of web accessibility issues on the part of web developers • In a survey by Lopes et al. (2010), 85% of web developers indicated the need for more accessibility training and the need for knowledge in fields such as inclusive design, as well as about users of assistive technologies. • Including the potential users in the design process of web content • In a recent survey (Yesilada et al., 2015) answered by 300 accessibility experts, the respondents strongly agree that accessibility must include the potential users in the process of design and evaluation, and that accessibility evaluation is more than just inspecting source code • The links between academic research and industry • Most developed interfaces in academic research are not made available to the public after the project ends. Our work: understanding and supporting collaborative web search between visually impaired and sighted users • Study 1: Understanding collaborative web search between visually impaired and sighted users • Aim: Investigate the challenges faced and behaviour patterns that occur when visually impaired and sighted users search the web together. • Study 2: Supporting collaborative web search between visually impaired and sighted users • Aim: Enhancing the accessibility of collaborative web search interface to support integration of visually impaired employees in a workplace Findings from our work relevant to the discussion today: • The need for overviews of webpages to save time exploring them with the limited mechanisms of a screen reader. • Accessibility of a web component and the work load associated with it can affect the visually impaired users choice of use. • Hot keys were important in allowing visually impaired users to perform certain tasks more efficiently and to quickly navigate around webpages. • We found evidence that integrated systems where the actual search box is on the same page as the search results and information about previous searches etc. was a good model for visually impaired users. I.e. integrated single web page applications can work well providing their components are accessible and it is easy to jump between major components. Our publications • Al-Thani, D., Stockman, T., and Tombros, A. (2015) The Effects of Cross-modal Collaboration on the Stages of Information Seeking. In Proceedings of 16th International Conference Interacción 2015. Vilanova i la Geltrú, Spain. • Al-Thani, D., Stockman, T., and Tombros, A. (2013). Cross-modal collaborative information seeking (CCIS): an exploratory study. In Proceedings of the 27th International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference, pages 16-24. British Computer Society. • Sahib, N. G., Al-Thani, D., Tombros, A., and Stockman, T. (2012). Accessible information seeking. In Proceedings of Digital Futures, Aberdeen, Scotland. References • Borodin, Y., Bigham, J. P., Raman, R., and Ramakrishnan, I. V. (2008). What’s new?: making web page updates accessible. In Proceedings of the International SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, pages 145–152, New York. ACM. • Borodin, Y., Mahmud, J., Ramakrishnan, I., and Stent, A. (2007). The HearSay non-visual web browser. In Proceedings of the 2007 international cross-disciplinary conference on Web ac-cessibility (W4A), pages128–129 . New York, NY. • Brajnik, G. (2006). Web accessibility testing: when the method is the culprit. Computers Helping People with Special Needs, 156–163. • Brown, A., Jay, C., Chen, A. Q., and Harper, S. (2012). The uptake of Web 2.0 technologies, and its impact on visually disabled users. Universal Access in the Information Society, 11(2):185–199. • Harper S, Jay C, Michailidou E, Quan H. Analysing the visual complexity of web pages using document structure. Behaviour \& Information Technology. 2013 April; 32(5): 491-502. eScholarID:215458 | DOI:10.1080/0144929X.2012.726647 • Lopes, R., Van Isacker, K., and Carriço, L. (2010). Redefining assumptions: accessibility and its stakeholders. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs, pages 561–568. Springer. • Lunn D, Harper S, Bechhofer S. Identifying Behavioral Strategies of Visually Impaired Users to Improve Access to Web Content. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2011 April; 3(4): 13:1-13:35. eScholarID:147933 | DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1952388.1952390. • Mahmud, J. U., Borodin, Y., and Ramakrishnan, I. V. (2007b). Csurf: a context-driven non-visual webbrowser. In Proceedings of the International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), pages 31–40,New York. ACM. • Murphy, E., Kuber, R., McAllister, G., Strain, P., and Yu, W. (2007). An empirical investigation into the difficulties experienced by visually impaired internet users. Universal Access in the Information Society, 7(1-2):79–91. • Newell, A. F., Gregor, P., Morgan, M., Pullin, G., and Macaulay, C. (2011). User-sensitive inclu-sive design. Universal Access in the Information Society, 10(3):235–243 • Sahib, N. G., Tombros, A., and Stockman, T. (2015). Evaluating a search interface for visually impaired searchers. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. • Salampasis, M., Kouroupetroglou, C., and Manitsaris, A. (2005). Semantically enhanced browsing for blind people in the WWW. In Proceedings of the Conference on Hypertext and Hypermedia (HYPERTEXT), pages 32–34, New York. ACM. • Shneiderman, B. (2000). Universal usability. Communications of the ACM, 43(5):84–91. • Sloan, David, Heath, A., Hamilton, F., Kelly, B., Petrie, H., and Phipps, L. (2006). Contextual web accessibility - maximizing the benefit of accessibility guidelines. In Proceedings of the 2006 international cross-disciplinary workshop on Web accessibility (W4A): Building the mo-bile web: rediscovering accessibility? (W4A ’06), pages 121–131). New York, NY, USA: ACM. • Susini, P., Vieillard, S., Deruty, E., Smith, B. and Marin, C. (2002) Sound Navigation: Sonified Hyperlinks. Proceedings of the International Conference on Auditory Display(ICAD2002), kayoto, Japan. • Yesilada Y, Brajnik G, Vigo M, Harper S. Exploring perceptions of web accessibility: a survey approach. Behaviour \& Information Technology. 2015; 34(2): 119-134. eScholarID:278836