W O R K I N G A Description and Analysis

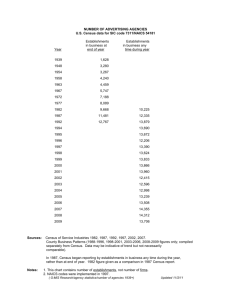

advertisement