A S T R A T E G... C o d i n g b o...

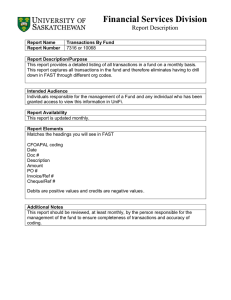

advertisement