........ LE P ~ Charlotte Baldwin Susanne Becken

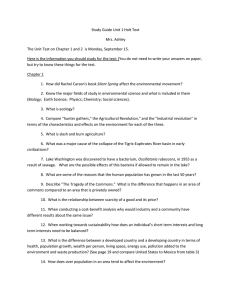

advertisement