(N -) C

advertisement

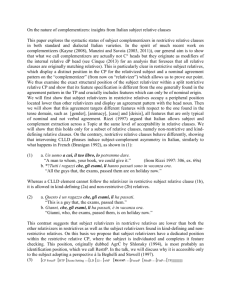

(NON-)SPECIFICITY MARKING IN RESTRICTIVE RELATIVE CLAUSES IN CATALAN SIGN LANGUAGE (LSC) INTRODUCTION. Although we already count on some previous work on relative clauses in signed languages (Branchini 2006; Branchini et al. 2007; Pfau & Steinbach 2005), the codification of the different types of specificity that relative clauses encode has not been studied yet. Moreover, (non-)specificity marking, which has been studied in a broad variety of spoken languages (von Heusinger 2011; Matthewson 1998), is still an understudied field in signed languages. In this paper, we offer a descriptive analysis of the expression of specificity in restrictive relative clauses in Catalan Sign Language (LSC). DATA. From a syntactic point of view, relative clauses in LSC are circumnominal (1a), instead of adnominal (1b), which appears to be the strategy used in the most thoroughly studied languages. This means that the pivot noun phrase appears inside the relative clause. As shown in (2), LSC relative clauses cannot occur internal to the matrix clause; instead they must be fronted or postposed. Also, note that the non-manual markers have scope over the whole relative clause and do not spread beyond this constituent. From a semantic point of view, LSC shows an overt contrastive marking of the semantic-pragmatic notions of (non-)specificity by localising the noun phrase on different regions of the signing space. The frontal plane, which extends parallel to the signer’s body, is grammatically relevant for the encoding of specificity and the two areas of the frontal plane, namely upper and lower, are associated with two different interpretations. When the noun phrase is associated with the lower frontal plane, a specific interpretation arises (Fig. 1). That is, it denotes a referent known by at least the sender. In contrast, when the localisation is associated with the upper frontal plane a non-specific reading is available, meaning that it denotes a referent not known by the sender or the addressee (Fig. 2). PROPOSAL. After an analysis of a small scale LSC corpus, which includes naturalistic and elicited data, we propose that relative clauses in LSC encode specificity marking. We show that three main strategies are used to encode (non-)specificity, as summarised in Fig. 3: (i) The localisation of the pivot noun phrase on the frontal plane differs according to the knowledge the signer has of the discourse referent. While in specific relative clauses the pivot is strongly associated with the lower frontal plane (that is, with a tensed realisation of the movement directed towards a concrete locus in signing space), non-specific ones are localised on the upper frontal plane, but they are weakly localised (that is, with a relaxed and non-tensed realisation to a bigger and wide-spread locus). (ii) Different non-manuals codify the degree of knowledge of the discourse referent. Squinted eyes spread over relative clauses when the specific pivot denotes shared information. When the pivot denotes a specific but non-shared discourse referent, the signer uses eyes wide open. Non-specificity occurs with sucked cheeks and a shrug. The weak localisation on the upper frontal plane co-occurs with a non-fixed eye gaze towards the locus. (iii) LSC relative clauses may require either an overt or covert nominalizer, which is instantiated by a sign glossed as MATEIX (‘same one’). However, this sign only appears in context of specificity when the information is shared among the participants. Two other signs, glossed as CONCRET (‘concrete’) and REQUERIMENT (‘requirement’), which denote an established subset, appear in both specific and non-specific contexts when the information is non-shared. The use of lexical signs appears to be non-compulsory. CONCLUSIONS. In this paper we shed new light on the syntax-semantics interface of sign languages, and more concretely on relative clauses in an understudied language, such as LSC. We investigate three main strategies that distinguish different (non-)specificity and (non-)shared information marking: spatial localisation, non-manual markers and the use of lexical signs. EXAMPLES AND FIGURES (1) (2) rel a. [CAT FEATURE OBEDIENT REQUERIMENT] IX1 WANT BUY LSC b. I want to buy [a cat [that is obedient]] English a. *JOAN [BOOK YESTERDAY BUY] BRING NOT in situ rel b. [BOOK YESTERDAY BUY] JOAN BRING NOT Joan hasn’t brought the book that he bought yesterday fronted rel c. JOAN BRING NOT [BOOK YESTERDAY BUY] Fig 1. Localisation of specific NPs Spatial localisation Specific NPs Nonspecific NPs Shared info Nonshared info Lower and strong localisation Upper and weak localisation postposed Fig 2. Localisation of non-specific NPs Non-manual markers Head tilt Squinted eyes Head tilt Open eyes Lower cheeks, shrug, not-fixed eye gaze (Non-compulsory) lexical signs MATEIX CONCRET REQUERIMENT Fig 3. Strategies for (non-)specificity marking REFERENCE LIST Branchini, C. 2006. On relativization and Clefting in Italian Sign Language LIS. Doctoral dissertation. Università di Urbino. Branchini et al. 2007. Relatively similar: Relative clause typology and sign languages. Paper presented at the 2nd conference of the Association Française de Linguistique Cognitive (AFLiCo). Lille, May. von Heusinger, Klaus. 2011. Specificity. In K. von Heusinger & C. Maienborng & P. Portner (eds.), Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning, Berlin: de Gruyter, 1024-1057. Matthewson, Lisa 1998. Determiner Systems and Quantificational Strategies: Evidence from Salish. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics. Pfau, Roland & Markus Steinbach. 2005. Relative clauses in German Sign Language: Extraposition and reconstruction. In Bateman, L. & C.Ussery (eds.), Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS 35), Vol. 2. Amherst, MA: GLSA, 507-521.