Document 12886824

advertisement

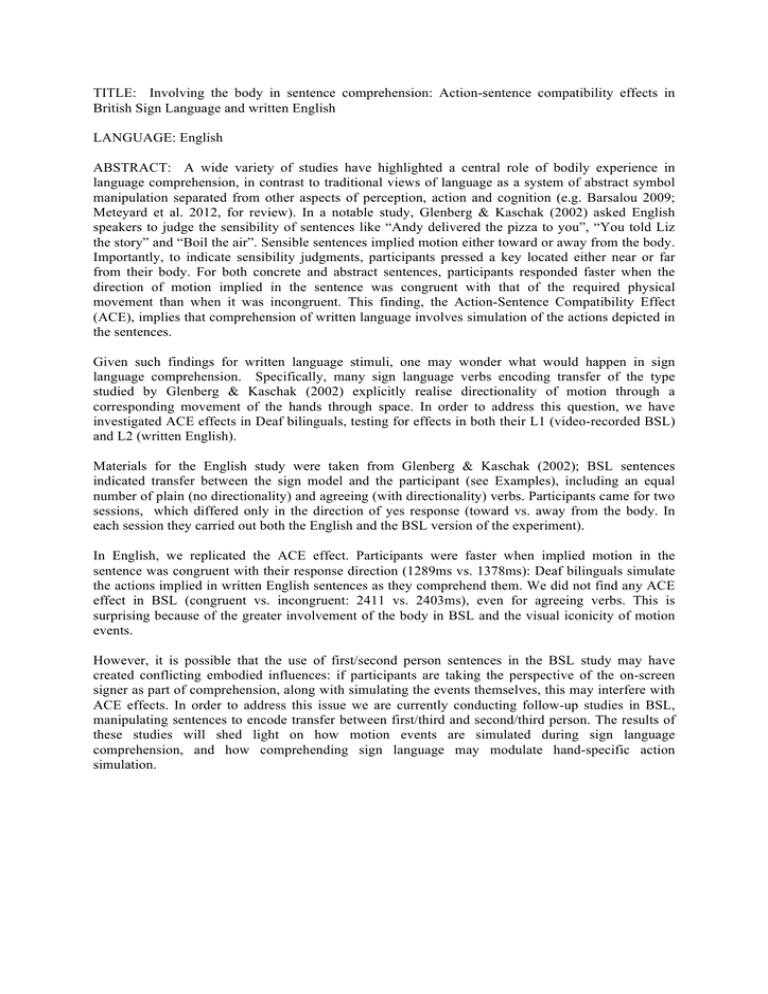

TITLE: Involving the body in sentence comprehension: Action-sentence compatibility effects in British Sign Language and written English LANGUAGE: English ABSTRACT: A wide variety of studies have highlighted a central role of bodily experience in language comprehension, in contrast to traditional views of language as a system of abstract symbol manipulation separated from other aspects of perception, action and cognition (e.g. Barsalou 2009; Meteyard et al. 2012, for review). In a notable study, Glenberg & Kaschak (2002) asked English speakers to judge the sensibility of sentences like “Andy delivered the pizza to you”, “You told Liz the story” and “Boil the air”. Sensible sentences implied motion either toward or away from the body. Importantly, to indicate sensibility judgments, participants pressed a key located either near or far from their body. For both concrete and abstract sentences, participants responded faster when the direction of motion implied in the sentence was congruent with that of the required physical movement than when it was incongruent. This finding, the Action-Sentence Compatibility Effect (ACE), implies that comprehension of written language involves simulation of the actions depicted in the sentences. Given such findings for written language stimuli, one may wonder what would happen in sign language comprehension. Specifically, many sign language verbs encoding transfer of the type studied by Glenberg & Kaschak (2002) explicitly realise directionality of motion through a corresponding movement of the hands through space. In order to address this question, we have investigated ACE effects in Deaf bilinguals, testing for effects in both their L1 (video-recorded BSL) and L2 (written English). Materials for the English study were taken from Glenberg & Kaschak (2002); BSL sentences indicated transfer between the sign model and the participant (see Examples), including an equal number of plain (no directionality) and agreeing (with directionality) verbs. Participants came for two sessions, which differed only in the direction of yes response (toward vs. away from the body. In each session they carried out both the English and the BSL version of the experiment). In English, we replicated the ACE effect. Participants were faster when implied motion in the sentence was congruent with their response direction (1289ms vs. 1378ms): Deaf bilinguals simulate the actions implied in written English sentences as they comprehend them. We did not find any ACE effect in BSL (congruent vs. incongruent: 2411 vs. 2403ms), even for agreeing verbs. This is surprising because of the greater involvement of the body in BSL and the visual iconicity of motion events. However, it is possible that the use of first/second person sentences in the BSL study may have created conflicting embodied influences: if participants are taking the perspective of the on-screen signer as part of comprehension, along with simulating the events themselves, this may interfere with ACE effects. In order to address this issue we are currently conducting follow-up studies in BSL, manipulating sentences to encode transfer between first/third and second/third person. The results of these studies will shed light on how motion events are simulated during sign language comprehension, and how comprehending sign language may modulate hand-specific action simulation. Examples (1) FUNDING ME 1-GRANT-2 I grant you the funding. (agreeing verb, abstract event) (2) CARDS YOU DEAL ME You deal me the cards. (plain verb, concrete event) References Barsalou, L.W. (2009). Simulation, situated conceptualization, and prediction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: Biological Sciences, 364, 1281-1289. Glenberg, A.M. & Kaschak, M.P. (2002). Grounding language in action. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(3), 558-565. Meteyard, L., Rodriguez Cuadrado, S., Bahrami, B. & Vigliocco, G. (2012). Coming of age: a review of embodiment and the neuroscience of semantics. Cortex, 48(7), 788-804.