Handedness in deaf signers

advertisement

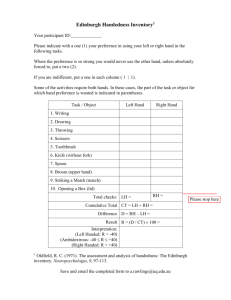

Handedness in deaf signers Language of presentation: English Signers use their hands as the main articulators, yet handedness remained a relatively neglected area in the study of sign languages until recent years. Here we report a series of studies investigating hand preferences of deaf signers, in signing and other activities, using both questionnaire responses and observational methods. First, we analyzed hand choice in signing based on the annotations of the Corpus NGT (Crasborn, Zwitserlood & Ros, 2008) and found three distinct patterns of hand preference. Most of the 92 signers (88%) in this corpus are right-handed, 5% are left-handed and 7% do not show strong hand preference. This incidence of right-handedness is similar to that found in various hearing populations, and contradict earlier results of increased non-righthandedness among the deaf (e.g. Dane and Gümüstekin, 2002), at least as far as signers’ handedness for signing is concerned. However, compared to previous research (in particular, Sharma, p.c.), we found more ambilateral signers but fewer left-handers. A second study investigated differences between right-, left- and mixed-handed signers by looking at hand dominance in spontaneous signing. Participants were chosen from the Corpus NGT by including all left-handed (N=5) and mixed-handed (N=6) participants and matching right-handed participants (N=9) on age and gender. Video recordings from each participant were annotated sign-by-sign for hand dominance and sign type (that is whether a sign was one-handed or two-handed, symmetrical or asymmetrical). Group level differences were found between right-, left- and mixed-handed signers for all sign types. Signers differed both in the direction and strength of lateralization, right-handers showing slightly stronger preferences than left-handers, while mixed-handed signers’ hand preferences were weak. Hand preference was not uniform among various sign types, as asymmetrical two-handed signs were more often articulated by the preferred hand than one-handed signs. Further analysis revealed differences between handedness groups in the number of dominance reversals (switches of hand dominance during signing). Mixed-handed signers switched dominance most often, followed by left-handers, while right-handers showed the fewest reversals. In a third study, we invited Corpus NGT participants to fill in an online questionnaire about handedness in everyday life as well as signing. After taking into account a selfselection bias among the 55 respondents (left-handers were more likely to respond), handedness based on questionnaire responses regarding everyday activities showed a similar distribution as in the general population. However, 9% of respondents show a mismatch between the direction of handedness for signing and other activities (for example, writing with the left hand but signing with the right or vice versa). This mismatch is not explained by a history of either forced change of handedness or injury. Further analysis will focus on whether any characteristics can be identified that set these signers apart. We will discuss the main findings from these studies and argue that these results suggest that a more nuanced picture of handedness for signing is necessary. The relevance of this issue for a range of research areas across the fields of linguistics, psycholinguistics and neuroscience will be addressed. References Crasborn, O., Zwitserlood, I., & Ros, J. (2008). Corpus NGT: An open access digital corpus of movies with annotations of Sign Language of the Netherlands. Centre for Language Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen. Available online: http://www.ru.nl/corpusngtuk. Dane, S., & Gümüstekin, K. (2002). Handedness in deaf and normal children. International Journal of Neuroscience, 112(8), 995–998.