Argument ellipsis in American Sign Language: When there is no... Sign languages (SL) grammaticalize the space utilized during utterance production:...

advertisement

Argument ellipsis in American Sign Language: When there is no space for space

Sign languages (SL) grammaticalize the space utilized during utterance production: verbs

may move in space to indicate agreement (Lillo-Martin 1991), spatial loci may be

interpreted as cases of personal/temporal anaphora (Schlenker 2011, i.a.), higher/lower

planes may be associated with different types of referents (Berberà 2012), etc. One might

say that the use of, and reliance on, space is one of the characteristics that differentiates

spoken and signed languages and, potentially, clouds a comparison between the two. We

show that the ‘removal’ of this characteristic, while preserving the authenticity of Sign

discourse, allows to generalize across modalities in addressing a cross-linguistically

contentious issue. We examine a SL phenomenon which has been argued to necessarily

employ spatial modifications—argument omission. We demonstrate that, contrary to the

aforementioned view, the ‘identifying’ use of space can be made unavailable. In such

cases, the null arguments in American Sign Language (NAASL) are best viewed as

resulting from argument ellipsis (AE) of a bare NP.

Bahan et al. (2000) argue that the NAASL necessarily involves spatial modification

((non-)manual agreement), as in (1)-(2). They conclude that both the null subject and the

null object (subject only illustrated here) instantiate agreement-licensed/-identified silent

pronoun pro (Rizzi 1986). However, we show that this in not always the case. We present

informants with ‘whispered’ sentences, in which the size of the signing space is

drastically reduced, and (non-)manual identification of loci of arguments is impossible.

In such cases, the NAASL behaves differently from a pro(noun): our informants judge the

NAASL in (3)-(4) as ambiguous between the strict and the sloppy readings—a hallmark of

AE (Oku 1998).

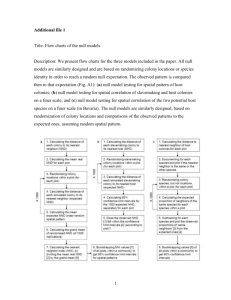

AE has been argued to result from either the lack of morphological agreement in

the language (Saito 2007, Takahashi 2010), or the ability of arguments to be predicates

(Tomioka 2003). We present evidence that both conditions are necessary for the NAASL.

Contrary to MacLaughlin (1998), we show that ASL behaves as a language without a

lexical item for an iota-operator (‘the’); e.g. (5) demonstrates that the typical contender

for this role –‘IX’—cannot serve as such an element. In such a language, bare NP can be

predicates, i.e. have either kind, definite, or indefinite readings (Chierchia 1998). This

approach allows for the NAASL in ellipsis configurations to have a range of

interpretations, the existence of which our consultants confirm. For (3), this means that

the number of wizards that came to A’s house may not the same that the number of

wizards that came to B’s house; for (4), this means that Jeff may hate students in general.

Our approach also explains why other types of arguments cannot be elided (e.g.

AP or CPs in (5)). We suggest that what is elided in ASL is an element serving as both a

head and a phrase—a possibility stemming directly from the absence of the DP (Abney

1987) in the language, since in languages without ‘the,’ bare NPs have been argued to

head the nominal projection (vs. being complements of a Determiner), see Boskovic

2010).

Word count: 500

Argument ellipsis in American Sign Language: When there is no space for space

(1) a. Øi [+agri ]AgrS [+agrj ]AgrO iSHOOTj FRANKj

‘(He/She) shoots Frank.’

__________

_________

head tilt-i

eye gaze-j

b. Øi [+agri ]AgrS [+agrj] AgrO iSHOOTj FRANKj

(2) a. * Øi [+agri ]AgrS [+agrj ]AgrO LOVE MOTHERj

‘(He/She) loves mother.’

head tilt-i

b. Øi [+agri ]AgrS [+agrj]AgrO LOVE MOTHERj

(3) A: THREE WIZARDS COME VISIT MY HOUSE

‘Three wizards came to my house’

B: Ø STAY MY HOUSE ONE-WEEK.

‘ ({The samestrict/differentsloppy} wizards) stayed in my house for a week’

(4) a-PETER LIKE a-POSS STUDENT. b-JEFF HATE Ø

‘Peter likes his students. Jeff hates ({Peter’sstrict/Jeff’ssloppy} students)’

________t

_________________wh ?

(5) a. FRANCE (*IX) CAPITAL WHAT

‘What’s *(the) capital of France?’

(6) a. MARY FEEL HAPPY ABOUT neu-POSS TEST, PAUL NOT FEEL THAT/*Ø

‘Mary feels good about her test, Paul does not feel that’

b. MARY FELL TEACHER a-IX PREFER BOOK PAPER, PETER NOT FEEL THAT/*Ø

‘Mary feels that the teacher prefers paper-made books, but Peter does not feel that.’

References:

Bahan, B., Kegl, J., Lee, R. G., MacLaughlin, D., & Neidle, C. (2000). The licensing of

null arguments in ASL. LI, 31(1), 1-27.

Barberà Altimira, G. (2012) The meaning of space in Catalan Sign Language (LSC).

Reference, specificity and structure in signed discourse. PhD. Dissertation.

Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Lilllo-Martin, D. (1991). Universal Grammar and American Sign Language: Setting the

Null Argument Parameters. Kluwer.

Oku, S. (1998). LF copy analysis of Japanese null arguments. Papers from the Regional

Meetings, CLS, 34(1), 299-314.

Tomioka, S. (2003). The semantics of Japanese null pronouns and its cross-linguistic

implications, in Schwabe, K. & S. Winkler (eds.) The Interfaces: Deriving and

Interpreting Omitted Structures. John Benjamins.

Schlenker, P. (2011) Temporal and Modal Anaphora in Sign Language (ASL). Paper

presented at FEAST1 Colloquium, Venice, Italy.