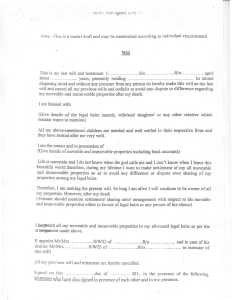

A W C

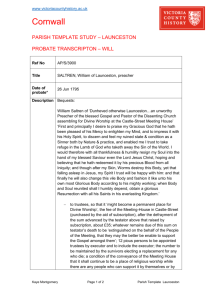

advertisement