Document 12884647

advertisement

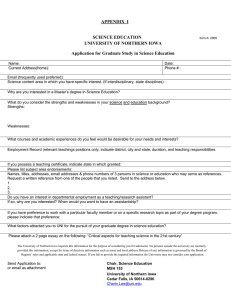

Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Volume 1, Number 1, June 2010, pp. 46-52 Enhancing Student Learning Through Evidence, Self-Assessment, and Accountability: Closing the Loop Mary Herring Barry Wilson University of Northern Iowa Our teacher education program had developed good assessments and a system for managing and reporting data. While we were well informed with respect to areas of the program in need of attention, we had not developed procedures and processes to change in systemic ways. The paper describes recent efforts to develop those procedures and processes and move toward a culture of change informed by our assessment system. Calls for reform in teacher education have emphasized the need for preparation programs to demonstrate that teaching candidates impact student learning. Preparing institutions are also charged with developing procedures for continual improvement based on careful program assessment (Henning, Kohler, Robinson, & Wilson, 2010). The focus on accountability, evidence of learning, and continual improvement is part of accreditation as well as public expectations (National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education, 2008; Wilson & Young, 2005). The institutional challenges for developing such a “culture of evidence” are great as there are competing visions of what evidence matters (Wineburg, 2006) as well as competing interests and ideologies among various organizations that impact teacher education (Wilson & Tamir, 2008). Finally, within our University of Northern Iowa (UNI) program, mechanisms for change based on assessment were not well-established. This paper describes our journey in moving from data collection and reporting to use of data to inform program improvement. The development of our assessment system has been guided by state accreditation and institutional guidelines. Assessment of student learning is defined at UNI as follows: Assessment of student learning is a participatory, iterative process that: a) provides data/information you need on your students’ learning; b) engages you and others in analyzing and using this data/information to confirm and improve teaching and learning; c) produces evidence that students are learning the outcomes you intended; d) guides you in making educational and institutional improvements; and e) evaluates whether changes made improve/impact student learning, and documents the learning and your efforts. (University of Northern Iowa, Office of Assessment, 2006) ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Correspondence: Barry Wilson, Department of Educational Psychology and Foundations, College of Education, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA 50613-0607. Email: Barry.Wilson@uni.edu. Author Note: This manuscript is a revised version of a paper presented at the 2009 conference of the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education. Additional information on specifics of our journey as well as completed Excel maps and mapping materials can be accessed at http://www.uni.edu/coe/epf/Assessment. Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation Volume 1, Number 1, June 2010, 46-52 Closing the Loop While the teacher education program has been collecting well-chosen performance assessment data for many years, we have not had a good process for making improvement across the program. During the past three years, with the support of an Iowa Teacher Quality Enhancement grant and our university administration, we have made a concentrated effort to “close the loop” on the assessment-change process. Our objective has been to develop procedures and processes that engage faculty in change based upon our performance assessment data. We will first briefly describe our program and assessment philosophy. The processes used to study and interpret our data will then be summarized. We conclude by describing the strategies we have employed to promote positive change in the program that can be institutionalized and sustained. Program and Assessment System Description Our initial licensure program for teachers is designed to meet the Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC) standards for beginning teachers. Iowa has also added a standard for the use and integration of technology and teaching. The knowledge, skills, and dispositions described in the standards provide the basis for the program, course objectives, and a description of essential learning outcomes. The teacher education conceptual framework emphasizes “educating for reflective and effective practice.” This serves as the theme and guiding principle for the program. This theme is reflected in our assessment philosophy and program goals. Assessment Philosophy and Program Goals Assessment is an essential and integral part of the continual process of learning and development at the university. The assessment plan is characterized by well-defined outcomes and multiple measures. While candidates are assessed in every class with a variety of assessment methodologies, university faculty have also chosen to emphasize assessment of teaching candidates engaged in teaching functions in real classrooms. These assessments are completed in four levels of field experiences. Professors also want to know how candidates think about teaching and learning and how they make sense of student learning so they have integrated the Teacher Work Sample (TWS) into the assessment process. The information gained through assessment is 47 used to facilitate candidate learning and development, to promote faculty and staff growth, and to improve the quality of academic and nonacademic programs and services. UNI’s initial licensure program for teachers is designed to meet the Iowa Renaissance standards for beginning teachers. All courses that lead to teacher licensure are required to align their course outcomes to the standards. Student Outcomes and Assessments Teaching candidates are assessed against the Iowa Renaissance Standards (INTASC standards plus technology standards). These include standards for (a) content knowledge, (b) learning and development, (c) diverse learners, (d) instructional strategies, (e) classroom management, (f) communication, (g) planning instruction, (h) assessment of learning, (i) foundations, reflection and professional development, school and community relations, and (j) integration of technology. Assessment of student learning is a critical part of the learning process (Shepherd et al., 2005). Our student outcomes are described in detail on our teacher education website (http://www.uni.edu/teached) and are also reflected in the rubrics used to assess candidate performance. Candidates are informed of these learning outcomes from the time of admission. Their progress in meeting standards is assessed and feedback provided throughout the preparation program via an online system. Teaching candidates are assessed in each of their courses using a variety of assessment methodologies including assessment of written work in journals and essays. Critical assessments are completed in each of their field experiences at Level I, Level II, Level III and Student Teaching. These assessments include evaluations by cooperating teachers and university supervisors as well as the Teacher Work Sample (or for early experiences, a modified TWS). Also employed in program assessment are indirect methods including surveys of student teachers, alumni, and principals. The UNI Teacher Work Sample was originally developed in partnership with 11 other Renaissance Group universities as a tool for instruction and performance assessment of teacher candidates. The TWS is a narrative description of a unit taught by a student teacher in their first placement. The TWS is guided by a prompt that indicates the essential information to be included in the narrative. It is read and scored analytically by university faculty and area teachers who use a common rubric. The TWS provides both quantitative and qualitative data that has been very 48 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation helpful in program assessment as well as candidate assessment. Preparation for developing the work sample is part of all field experiences. Teaching candidates are also evaluated in each clinical experience. The TWS has been found to be a source of useful evidence on whether candidates have learned and can also demonstrate learning among their students (Henning & Robinson, 2004; Henning et al., 2010). Student teachers are evaluated by their cooperating teachers and university supervisors who use a Renaissance Standards-based evaluation form. The evaluation is based upon a rubric which describes expectations for performance at each level of the scale. Evaluations of earlier field experiences have a similar structure and rubric. These include the following: • Level 1 evaluations are initial clinical experiences conducted in area schools. All candidates are evaluated and complete a TWS component. • Level II evaluations are clinical experiences completed at the Price Laboratory School and Professional Development schools. All candidates are evaluated and complete a TWS component. • Level III evaluations are clinical experiences completed during methods coursework. Most include an evaluation and TWS component. Candidates must pass the Praxis I to be admitted to the program. The Educational Testing Service publishes the Praxis series. Praxis I is designed to assess the basic skills of reading, math, and writing and is required for admission to teacher education. Praxis II is only taken by elementary majors. It is designed to assess the content knowledge of our candidates and is required by the state of Iowa. Praxis II is taken at prior to recommendation for a teaching license. In addition to key assessments used in the accountability system, candidates are assessed in each course using various methodologies. Learning outcomes, course objectives, and INTASC standards addressed in each course are included in course syllabi. Candidates must meet GPA requirements in order to advance at each decision point in the program. Each course in our preparation program is designed to help candidates achieve learning outcomes specified in our Renaissance standards. Assessments need to build on one another so that the assessments conducted as end-of-program assessments are supported at the course level. Management and Interpretation of Data The university has developed a data management system called UNITED (UNI Teacher Education Data; see http://www.uni.edu/ teached/license/monitor.shtml) to manage data used for candidate and program assessment. The UNITED system has been in place since 2003. The system provides controlled access for candidates, advisors, faculty, and administrators. Candidates are enrolled on the system at the time of admission and have access to specific program requirements and timely feedback on key assessments including clinical experience evaluations, GPAs, and Teacher Work Sample scores as they move through four key decision points. Key assessment data are entered by course instructors and staff. The system also has a report function that supports aggregation of key assessment data for program assessment. In addition to data managed by the UNITED system, periodic surveys are collected from student teachers, alumni, and school principals. Program assessment data has been compiled for over five years. The convergence of the data over time is quite remarkable. We get very consistent evidence regarding areas of relative strength and weakness. Until recently, however, there were no established procedures and processes to move from assessment to taking coordinated action to address identified areas of program weakness. Strategies for Change In the fall of 2005, the state of Iowa received a $6.2 million Teacher Quality Enhancement (TQE) grant. Part of the grant provided for the development and/or refinement of assessment systems. The timing of the grant was fortuitous and provided modest support for developing change in response to data collected. The UNI program was awarded a small TQE grant for the 2006-07 academic year to support engaging faculty in the program improvement phase of assessment. The process for change was led by our interim director of teacher education, our director of assessment, and key faculty in consultation with our Council on Teacher Education. Our discussions indicated a clear need to identify where and how INTASC standards were being addressed in the program. For that reason, our first TQE grant provided support for faculty to renew and revisit our INTASC curriculum map. As Maki (2004) notes, maps of the curriculum stimulate reflec- Closing the Loop tion on collective learning priorities and provide a visual representation of student learning. Curriculum Mapping Project Our mapping process was guided by Hale’s (2005) Tenets of Curriculum Mapping. Key elements that we have adopted include the use of technology, datadriven change, collaborative inquiry and dialogue, and action plans to design and facilitate sustainable change. The goals of the mapping project were to address gaps as well as unnecessary redundancies in the program, better articulate the program, and improve communication internally and externally (particularly with community college partners). The resulting product provided a program picture in the form of elementary and secondary curriculum maps in an Excel spreadsheet. The maps not only showed where standards were being addressed but also at what level they were being attained and how they were assessed. Curriculum Mapping Process Faculty were asked to map their individual courses and attended meetings to discuss the process and resulting product. Decision rules were developed to suggest the degree to which a standard was addressed. Mappers used I/R (introduce and reinforce) to represent introductory activities while E/P (extend and perform) represented advanced treatment or classroom application of the standard. Reaching consensus required extensive discussion but provided better clarity for map interpretation. For example, we agreed that participants could not map what they didn’t assess in some way. The process of developing curriculum maps required faculty to draw explicit connections between content, skills, and assessment measures at the course level. Faculty who taught in multiple-section courses were asked to develop a single consensus course map. This process encouraged the establishment of common goals between sections (horizontal articulation) so that the maps could be used for vertical articulation of the program. Mapping tools were created (see Figure 1) based on a standard’s knowledge, dispositions and performances. Training sessions were held, and upon the map’s completion, data was entered into an Excel spreadsheet. This allowed us to produce a dynamic document (see Figure 2). Moving the screen cursor over a box opens an activity note card that not only shows that the standard was addressed but also the learning activity or assignment used to assess the standard. The 2006-07 mapping project provided a visual representation of important segments of our program. Participant feedback also indicated that many faculty discovered that while they “covered content” related to the standards, they often did not use course assessments which identified that standards and expect- Figure 1 Example of Course Mapping Worksheet Standard #1: Content Knowledge Class Activities Participation Professional Demeanor Attendance Chapter Presentation Professional Portfolio Philosophy Paper Level III Field Experience Theorist Summary Chart Theorist Presentation Behavior Management Paper In Class Assignments Level III Notebook 1K 1 EP 1D 2 IP EP IR EP EP EP IR 3 1 IR 1P 2 IR 3 EP EP 4 IR 1 EP IR EP IR EP IR EP IR EP EP EP IR 2 3 EP IR IR EP 49 EP IR IR EP IR 4 5 6 EP EP IR IR EP 50 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation ations had been met. Feedback from mapping participants also included comments such as, “[Mapping] allowed me to look at components of class and how they can flow from one to another”; “Improvement of teaching/assessment”; and “I reevaluated assignments and credible assessments”. Figure 2 Dynamic Map Example. In 2007-08, UNI received a second small grant to expand the area of the curriculum map and engage more faculty in the process. In addition, it provided support for workshops on course assessment to help faculty link course assessment to specified learning outcomes represented in the curriculum map. Institutional Support: Professional Development Day With the support of our university administration, classes were canceled on February 29, 2008 for a professional development day for teacher education faculty. The goals of the day were to engage faculty in the interpretation of program assessment data, develop consensus on focused change, and develop tentative action plans for each program. Faculty were assembled in roundtable groups that represented a cross-section of majors and program components. In the first session, each of the 14 groups examined data summaries that included teacher work sample results, the curriculum maps, and student teaching evaluations. Each group was provided a laptop to capture responses to questions. Responses were transcribed and transmitted by a group recorder to a website facilitated by technology staff. The question for session one was: “Based on examination of the TWS, curriculum map, and student teaching data, what are areas in need of improvement?” Sample responses from 48 entries include the following: We need to possibly think about a field experience for diversity to address the lack of opportunity within the performance domain. Students currently do not have an opportunity to think about diversity in a "real-life" way maybe a community-based experience beyond the schools. There is a need for core objectives in multi-section courses to ensure continuity among multiple instructors (and year to year). In session two, faculty examined and interpreted survey data from alumni and student teachers. Groups responded to the question: “Based on your examination of surveys of student teachers and alumni, what appear to be elements in need of improvement for our programs as teacher candidates exit the program or begin teaching?” Responses from 40 entries included the following: Seems like alumni are asking for more practical experiences with differentiation. This includes writing and implementing IEPs and how this relates to assessment. Students do not feel competent with technology. Perhaps instruct technology acquisition skills instead of program usage. They will not likely have access to the specific software programs that are being taught. Closing the Loop In the third session, faculty were asked: “What 'aha's' did members of your table have based on data from the TWS, curriculum map, and student evaluations?” The following were within the 29 received: Human relations is more than diversity! This has challenged us to rethink the role of HR in the curriculum. We do not cross-fertilize very well. Many of the faculty commented that the day offered them a chance to reflect on the data presented, an opportunity to discuss data’s impact with teacher education faculty from other departments, and time to plan for next steps. Some common themes that emerged from the feedback collected included the continuing need for professional development and collaboration across program elements and an expressed desire to continue to work toward focused change. A third TQE grant applied for and received for 2008-09. Four teams of six faculty representing professional education, methods, and clinical experiences worked collaboratively to address improvements in targeted areas of improvement. The four areas targeted were assessment, diversity, instructional use of technology, and classroom management. The following charge was given to the four teams: 1. What improvements in your target area need to be addressed? (previous work on curriculum mapping may assist this conversation but we want you to focus on the courses or experiences your team members teach or supervise). a. To what extent does content in professional education and methods mesh and support needed conceptual understanding for application in the classroom? How can connections be improved? b. To what extent do clinical experiences provide opportunities for practice by teaching candidates? What supports might be added? 2. Given study and discussion by your team, what modifications in your own practice were suggested? What did you discover that might generalize to other faculty in teacher education? 3. Describe the process that led you to your action plan. What did you do as individuals? As a group? As a process? What would you suggest as a way to continue this kind of dialogue 51 and communication among teacher education faculty? The teams completed their work in the summer of 2009. Their findings and recommendations were received by the Council on Teacher Education in the fall of 2009. Areas of focus included assessment, diversity, classroom management, and using technology for instruction. Action plans submitted by the teams call for continued communication and collaboration among professional sequence, methods, and clinical experience faculty as well as continued scheduled opportunities for such work. During the 2009-10 academic year, a series of continuing meetings were held to incorporate recommendations of the teams as well as respond to Iowa Department of Education initiatives including the Iowa Core Curriculum. Closing the Loop: A Summary As the Higher Learning Commission (2005) has suggested, “assessment of student learning is an ongoing, dynamic process that requires substantial time; that is often marked by fits and starts; and that takes longterm commitment and leadership.” We have experienced a period in which we collected data that was not used for change. We had a program that was not well articulated. The courses that contributed to the program were not well connected. With the help of small TQE grants as well as strong internal administrative support and leadership, we are making use of data for change. Our teacher education program is better articulated. We are connecting courses and people and developing a common vision for change. In short, the university has developed a series of projects that promise to improve our preparation program through program evaluation and professional development support for faculty to promote positive change. We have learned that if a process is to be successful, attention to time constraints are a key. Campus support, provision of supporting documents and creation of processes allow faculty to focus precious time on the issues at hand and encourage participation. An open process helped to quell worries of hidden agendas and opened minds to looking at possibilities of change to improve our student’s preparation. Finally, our process has reminded us that significant change in programs needs to happen both vertically and horizontally from the course level to the program level and needs to be supported by continuing professional development for 52 Journal of Assessment and Accountability in Educator Preparation faculty (Walvoord & Anderson, 1999; Walvoord, 2004). We expect that our initial efforts at developing a culture of change will require continual monitoring as well as modifications as we learn from our experience. We will focus on sustaining the energy and conversations among faculty to “close the loop” and demonstrate continual improvement based on careful program assessment. References Hale, J. A. (2005). A guide to curriculum mapping: Planning, implementing, and sustaining the process. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Henning, J. E. & Robinson, V. (2004) The teacher work sample: implementing standards-based performance assessment. The Teacher Educator, 39, 231-248. Henning, J., Kohler, F., Robinson, V., & Wilson, B. (2010). Improving teacher quality: Using the Teacher Work Sample to make evidence-based decisions. Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield Higher Learning Commission (2005). Student learning, assessment, and accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.ncahlc.org/download/AssessStuLrng April.pdf Maki, P. L. (2004) Assessing for learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus. National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. (2008). Professional standards for the accreditation of teacher preparation institutions. Washington, DC: Author. Shepard, L., Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Rust, F., Snowden, J.B., Gordon, E., Guttierez, C., & Pacheco, A. (2005). Assessment. In L. DarlingHammond & J. D. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world (pp. 275-326). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. University of Northern Iowa, Office of Assessment (2006). A definition of assessment. Retrieved from http://www.uni.edu/assessment/definitionofassessment.shtml Walvoord, B. E. (2004). Assessment clear and simple: A practical guide for institutions, departments, and general education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Walvoord, B. E. & Anderson, V. J. (1998) Effective grading. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Wilson, S. M. & Tamir, E. (2008). The evolving field of teacher education: how understanding challenges might improve the preparation of teachers. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J McIntyre & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education. New York: Routledge. Wilson, S. M. & Youngs, P. (2005) Research on accountability processes in teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Wineburg, M. S. (2006). Evidence in teacher preparation: Establishing a framework for accountability. Journal of Teacher Education, 57, 51-64. Authors Mary Herring is the Interim Associate Dean of the University of Northern Iowa’s College of Education. Her research interests are related to distance learning. Barry Wilson is the Director of Assessment for the University of Northern Iowa's College of Education. His research interests are in the area of accountability systems and the impact of assessment data on educators and students.