NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES SAVING INCENTIVES FOR LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME FAMILIES: EVIDENCE

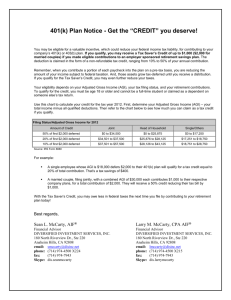

advertisement