Document 12877312

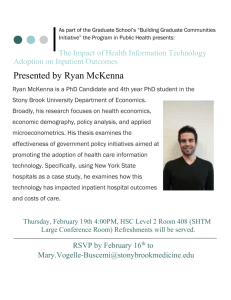

advertisement