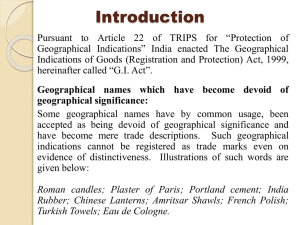

Geographical Indications

advertisement