T ARTICLES THE ADA-A LITTLE USED TOOL TO REMEDY NURSING HOME DISCRIMINATION

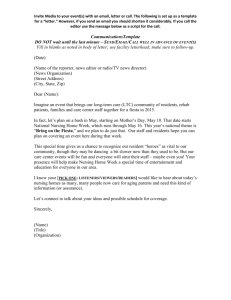

advertisement