. " "Dear Sister Antillico The Story of

advertisement

"Dear Sister Antillico

Kirksey*

WILLIAM

R.

CASTO** AND VAL

D.

" .• The Story of Kirksey v.

RICKS'**

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.

II.

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

323

A.

THE OBSCURITY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

323

B.

THE MYSTERY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

324

C.

THE FAME OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

326

WHAT HApPENED

327

A.

THE PARTIES

327

1.

Angelico Kirksey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

327

2.

Isaac Kirksey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

330

B.

III.

335

THE CONTROVERSY: WHY INVITE AND WHY EVICT?

THE LITIGATION . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . . . . .

353

A.

THE LAWYERS

..........•........................

354

B.

THE JUDGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

355

C.

THE TRIAL . . . . . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . .

356

D.

ISAAC'S NEW LAWYER FOR THE APPEAL • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

360

K

THE SUPREME COURT . . . • . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . . . . . .

361

F.

THE BRIEFS

362

.

* Both authors wish to thank the late Allan Farnsworth and Judith Maute and Joseph Perillo for

comments, as well as participants in the AALS Contracts section listserv, whose thoughts about Kirksey

v. Kirksey are reported anonymously below as coming from Professors A-Z. See infra Part IV.C.

(copies on file with authors).

** Allison Professor of Law, Texas Tech University. © 2006, William R. Casto and Val D. Ricks.

Professor Casto wishes to thank Dean Kenneth Randall for his support of tIlis project while Professor

Casto was the Tom Bevill Visiting Chairholder of Law at the University of Alabama. Professor Casto

also wishes to thank Professor Daniel Benson for his support from the Paul Whitfield Hom Professorship.

*** Vinson & Elkins Research Professor and Professor of Law, South Texas College of Law.

Professor Ricks wishes to thank Angela Wilderman, the nation's foremost expert on Kirksey family

genealogy; Norwood Kerr of the Alabama Archives; Monica Ortale and the Fred Parks Law Library at

South Texas College of Law; and, for valuable research, Derek Mueller and Dorian Cotlar.

321

[Vol.

94:321

THE OPINIONS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . .

365

AFTERWARDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • • • . . . • . . . . . .

370

A.

THE KIRKSEY OPINION IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY . . . . • . . . . .

372

B.

KIRKSEY IN THE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURIES . . . • .

372

C.

THE SECRET OF KIRKSEY'S SUCCESS

375

322

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

G.

IV.

V.

CONCLUSION........................................

ApPENDIX I: KIRKSEY TRIAL REcoRDS

.....•...........•........

1844-1846

A.

TALLADEGA CIRCUIT COURT RECORDS

B.

TALLADEGA COUNTY MINUTE BOOK CIRCUIT COURT

1840-1844 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

C.

382

383

383

386

CIRCUIT COURT TALLADEGA COUNTY, TRIAL DOCKET BOOK

1844-1844. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

387

II:

KIRKSEY APPELLATE REcORD. . . . . . . . . • . . . • . . . . . . . . .

387

ApPENDIX III: KIRKSEY IN VERSE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

395

ApPENDIX

Kirksey v. Kirksey

(Ala. 1845)

Error to the Circuit Court of Talladega.

Assumpsit by the defendant, against the plaintiff in error. The question is

presented in this Court, upon a case agreed, which shows the following facts:

The plaintiff was the wife of defendant's brother, but had for some time

been a widow, and had several children. In 1840, the plaintiff resided on

public land, under a contract of lease, she had held over, and was comfortably

settled, and would have attempted to secure the land she lived on. The

defendant resided in Talladega county, some sixty, or seventy miles off. On

the 10th October, 1840, he wrote to her the following letter:

"Dear Sister Antillico-Much to my mortification, I heard, that brother

Henry was dead, and one of his children. I !mow that your situation is one of

grief, and difficulty. You had a bad chance before, but a great deal worse now.

I should like to come and see you, but cannot with convenience at present.

* *

>1<

I do not !mow whether you have a preference on the place you live on, or not.

If you had, I would advise you to obtain your preference, and sell the land and

quit the country, as I understand it is very unhealthy, and I !mow society is

very bad. If you will come down and see me, I will let you have a place to

raise your family, and I have more open land than I can tend; and on the

account of your situation, and that of your family, I feel like I want you and

the children to do well."

Within a month or two after the receipt of this letter, the plaintiff abandoned

her possession, without disposing of it, and removed with her family, to the

[Vol. 94:321

365

370

372

RIES

372

375

382

383

383

386

: BOOK

387

387

395

2006]

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

323

residence of the defendant, who put her in comfortable houses, and gave her

land to cultivate for two years, at the end of which time he notified her to

remove, and put her in a house, not comfortable, in the woods, which he

afterwards required her to leave.

A verdict being found for the plaintiff, for two hundred dollars, the above

facts were agreed, and if they will sustain the action, the judgment is to be

affirmed, otherwise it is to be reversed.

Rice, for plaintiff in error, cited 4 Johns. 235; 10 id. 246; 6 Litt. 101; 2

Cowen, 139; I Caine's, 47.

W.P. Chilton and Porter, for defendant in error, cited I Kinne's Law Com.

216,218; Story on Can. 115; Chitty on Can. 29; 18 Johns. 337; 2 Peters, 182;

I Mar. 535; 5 Cranch, 142; 8 Mass. 200; 6 id. 58; 4 Maun. 63; I Conn. 519.

ORMOND, J.-The inclination of my mind, is, that the loss and inconvenience, which the plaintiff sustained in breaking up, and moving to the

defendant's, a distance of sixty miles, is a sufficient consideration to support

the promise, to furnish her with a house, and land to cultivate, until she could

raise her family. My brothers, however think, that the promise on the part of

the defendant, was a mere gratuity, and that an action will not lie for its

breach. The judgment of the Court below must therefore be reversed, pursuant

to the agreement of the parties.'

1.

INTRODUCTION

A. THE OBSCURITY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

The question is

allowing facts:

l for some time

"tiff resided on

vas comfortably

lived on. The

y miles off. On

rd, that brother

uation is one of

deal worse now.

e at present.

l live on, or not.

,ell the land and

know society is

have a place to

'Od; and on the

I want you and

.ntiff abandoned

'f family, to the

Kirksey v. Kirksey, quoted above in full, has become one of the most famous

cases in American contract law. The court's opinion, however, is quite ordinary.

It announces no new doctrine and neither elaborates nor explains established

doctrine. The anthor's writing style is not particularly impressive, and his

analysis-like his reputation-is obscure. Today courts might very well reach

the opposite result on similar facts. 2 For the most part, courts have ignored the

case. Aside from a few desultory citations in Alabama, 3 Kirksey received no

judicial attention whatsoever in the nineteenth century. Its last appearance in

Alabama was in 1891 as a bit player-the last case in a throw-away string cite.'

Nevertheless, forty years later Kirksey returned to the judicial stage-this time

1. 8AIa.131(1845).

2. Kirksey was decided before the advent of promissory estoppel, and there once was a modern

consensus that the plaintiff in Kirksey would prevail under a promissory estoppel theory. Langer v.

Superior Steel Corp., 161 A. 571, 572-73 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1932); see also JOHN MURRAY, MURRAY ON

CONTRACTS 228 n.37 (3d ed. 1990); Melvin Eisenberg, Donative Promises, 47 U. CHI. L. REv. 1, 19,

28-29 (1979); James Gordley, Enforcing Promises, 82 CAL. L. REv. 547, 579 (1995); Harry W. Jones,

An Invitation to Jurisprudence, 74 COLUM. L. REv. 1023, 1027-28 (1974). But see infra notes 408-11

and accompanying text.

3. Head v. Baldwin, 3 So. 293, 294 (Ala. 1887); Bibb v. Freeman, 59 AIa. 612, 617 (1877); Hubbard

v. Allen, 59 Ala. 283, 299 (1877); Hawkins v. Hndson, 45 AIa. 482, 495 (1871); Bowin & Co. v.

Sntherlin, 44 Ala. 278, 280 (1870); Morris v. Lewis' Executor, 33 Ala. 53, 57 (1858): Erwin & Williams

v. Erwin, 25 Ala. 236, 242 (1854); Forward v. Annstead, 12Ala. 124, 127 (1847).

4. See Hart v. Steele, 10 So. 243, 244 (Ala. 1891).

324

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 94:321

in Pennsylvania-as a "leading opinion."s Seventeen years later, Kirksey arrived in the Big Apple as a "famous case.,,6 After that there is nothing. Kirksey

has not been cited by a single court since 1949. Indeed, over the last 150 years,

Kirksey has been cited outside of Alabama on only three occasions."

B. THE MYSTERY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

Notwithstanding the surprising paucity of judicial citations, Kirksey truly is a

famous case. Most first-year students and all contracts professors know the

case's story of personal tragedy, good intentions gone awry, intrafamilial squabbling, and a broken promise. Kirksey is famous because it is a great teaching

case-especially for first-semester students. Although the case seems straightforward and even simple, many ambiguities and puzzles lie beneath its still

surface. Countless professors in countless classes have queried: Why did Isaac

Kirksey invite his sister-in-law "Antillico" (an aberrant spelling of Angelico, we

discovered8 ) down to Talladega? Was he bargaining for something when he did?

How many children did Angelico bring? Did Isaac mean for the children to

work on his plantation (did he bargain for their labor)? Did Isaac and Angelico

have an affair (was the consideration meretricious)? Why did Isaac move to

evict his sister-in-law? Was she unbearable as a neighbor? Why did she sue?

What result was she seeking? What evidence was presented at trial? Did she

have evidence of consideration other than her trip to Talladega? Was her lawyer

incompetent? Did the law of the time support Angelico's legal position, or is

Ormond's conclusion based on something other than legal authority? Did the

appellate court usurp the jury's factfinding role? Why did the dissenting judge

write the majority opinion? Whatever happened to Angelico and her small

children?9 The ensuing classrOOJ]l discnssion intrigues both professor and student. The case has even inspired poetry (of a sort). 10

Asking these questions serves pedagogy, though the questions are consistent

with as many pedagogical objectives as there are questions. Indeed, our informal poll of contract law teachers revealed a long list of objectives for which

professors use Kirksey. Because Kirksey is not a leading case, its very obscurity

leaves the professor free to take the case wherever she will. That is one reason

professors and students enjoy the case: it is delightfully ambiguous.

We intend to spoil that ambiguity and answer all of these questions. Henry

Kirksey, Angelico's late husband, was the poorer brother of the entrepreneurial

and litigious Isaac Kirksey, the writer of the letter. Though Isaac's invitation

suggests to us today that Isaac was kind and generous, Isaac had an ulterior

5. Langer, 161 A. at 572.

6. In re Baer's Estate, 92 N.Y.S.2d 359,361 (Surrogate's Ct. 1949).

7. In addition to the two cases cited in notes 5 and 6, supra, see Housman v. Commissioner of

Internal Revenue, 105 F,2d 973, 975 (2d Cir. 1939).

8. See infra note 21.

9. This question appears in Jones, supra note 2, at 1027-28.

10. See infra Appendix III.

.

[Vo!. 94:321

years later, Kirksey arJere is nothing. Kirksey

over the last 150 years,

occasions.?

,Y

tions, Kirksey truly is a

s professors know the

'ry, intrafamilial squabe it is a great teaching

case seems straightfor~s lie beneath its still

lueried: Why did Isaac

pelling of Angelico, we

omething when he did?

~an for the children to

)id Isaac and Angelico

Thy did Isaac move to

,or? Why did she sue?

ented at trial? Did she

adega? Was her lawyer

,'s legal position, or is

:gal authority? Did the

id the dissenting judge

ngelico and her small

lOth professor and stuluestions are consistent

ons. Indeed, our infor,f objectives for which

case, its very obscurity

vil!. That is one reason

mbiguous.

these questions. Henry

: of the entrepreneurial

)ugh Isaac's invitation

, Isaac had an ulterior

[ousman v. Commissioner of

2006]

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V.

KIRKSEY

325

motive. He meant to place Angelico on public land to hold his place-his

preference-so that he could buy the land later from the U.S. government at a

lucrative discount. He was bargaining for her to act as a placeholder, and she

knew it, though using that evidence later in court was problematic. We explain

why these facts are missing from the Kirksey opinion.

Angelico brought at least six and as many as nine children with her, but Isaac did

not bargain for labOl: He had many slaves. Nor was there an affair. In fact, Isaac

remarried, apparently happily, six months before inviting Angelico. Also, ,Angelico

was not unbearable as a neighbor. Isaac and Angelico had known each other for

twenty-five years. Isaac was married to Angelico's sister for eighteen of those years.

They had been neighbors earlier, near Huntsville, before Isaac moved to Talladega.

He knew what kind of neighbor she was when he invited her.

Isaac evicted Angelico because a change in the laws made Isaac ineligible to

buy government land at a discount, but the same law allowed Angelico a right to

the land on which Isaac placed her, at the same discount price Isaac had sought.

Only by evicting Angelico could Isaac hope to retain that land. Facts presented

at trial, as reported in the trial and appellate court records (attached to this

Article as appendixes) but omitted from the pnblished opinion, suggest Isaac's

motive for his invitation and the eviction. Angelico sned because she wanted the

land itself, we believe. The amount of the jury verdict-$200-is the much

discounted price charged by the government for such property.

Angelico's lawyer for both the trial and appeal, William Chilton, had a

sterling reputation. A former law parmer of the trial judge, Chilton replaced

Justice Ormond on the Alabama Supreme Court in 1848. Isaac's lawyer, Green

T. McAfee, a former Talladega County Judge, was perhaps less competent.

Isaac fired ,McAfee after the trial and hired Samuel Rice for the appeal. Rice

also later served on the Alabama Supreme Court, from 1855 to 1859. On appeal,

both Angelico and Isaac were represented by the state's rising legal stars.

The law of consideration at the time supported both the majority's opinion

and Justice Onnond's dissent. Two strands of consideration doctrine, one

focused on bargain and one focused on action taken in reliance, existed in

American contract law and the law of Alabama at the time. Ormond, the

dissenter, probably wrote the majority opinion because he was assigned the case

before it was argued. The court did not deem the case sufficiently important to

change the assigmnent.

Finally, Angelico stayed in Talladega County until May 1845. She paid Isaac's

court costs after the appeal was decided, then moved back nortll, to Madison County,

where she had first lived in Alabama. She later moved to Arkansas to live with her

son, and apparently died in the l860s. Isaac continued to prosper, gathering more land

and money about him for the next ten years. His fortune diminished only slightly in

the 1850s. Isaac died in 1865, at the end of the Civil War, leaving numerous creditors

and an estate large enough to litigate. I I

11. See Kirksey v. Kirksey, 41 Ala. 626 (1868).

326

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 94:321

C. THE FAME OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

::11

,;1

,I;

Answering Kirksey's mysteries showed us iliat no one who has ever taught the case

has had any real understanding of what actually happened. Our realization and the

case's obscurity caused us to ask why this case is in the casebooks at all. The answer

is a delightful story of the case's discovery by Samuel Williston. Williston origioally

thought of Kirksey as a conditional gift case. (Angelico may have been the mother of

Williston's tramp.)!2 But Williston changed his mind about Kirksey in the 1920s and

began to think of the facts of the case as fit for "promissory estoppel." The ambiguity

of the opinion made this change of mind possible. Williston's dual use of the case

embedded it in his teaching, his treatise, his mind, and his students' minds, until the

case became one of contract law teaching's prirruuy sources. Ironically, the opinion's

rise to fame was only possible because of its mystery-what the case does not say, its

obscurity, has made it available to teachers who wish to provoke students' analytical

skills with the possibilities that Justice Onnond's sparse opinion leaves open.

In this Article, we tell what actually happened in Kirksey v. Kirksey-the

story Ormond left out. We fill in the omission that made the case so valuable in

Williston's thinking. We tell the story chronologically, because it is a good

story. The story itself is important to the teaching of contract law. Kirksey's

primary significance today lies in its use as a tool for introducing students to

some of the more rudimentary aspects of the law of contracts. The Kirksey story

enhances and explains Kirksey's importance. Our research, and the story we tell,

center on resolving the mysteries suggested by the published opinion and the

opinion's later use in contract law teaching.

As we wrote, we discovered other narrower but valuable approaches----{)ther ways

to tell the story. First, and most obviously, Angelico's life as we know it is a tale about

patriarchy.!3 Second, the story might be told as a narrative about race relations.!4

12. See infra note 396 and accompanying text.

13. Angelico's role in life, from this view, was primarily to bear and care for children-fourteen of

them born over a twenty~six-year period, the last in 1838. When her husband died, his brother took up

her cause. On his default, she hired a male lawyer to sue before a male judge and twelve male jurors.

On appeal, three "fathers of the state" decided she should take nothing but instead should pay Isaac's

costs. There is only one woman in this legal tale, and everywhere she turns she is at the mercy of the

male-dominated culture and legal system. It may be coincidence that the loser of the case was a woman,

or not, but either way, Angelico's life is bound up in a patriarchal worldview. We did not expect to see a

different pattern, actually, given the time period. Angelico died while dwelling in her son's home. We

do not know whether the illiterate Angelico was happy with her role Or not. She personally has no

explicit voice in the story, except through what the men in the story chose to say for her. No plaintiff

was allowed to testify in her own cause at the time. Blann v. Beal, 5 Ala. 357 (1843); Watkins v.

Watkins, 2 Stew. 485 (Ala. 1830).

)

,

14. Isaac's many slaves were key to both his desire for land and the increasing wealth that allowed

him to act, or seem to act, generously toward Angelico. Isaac's relations with his slaves also reveal

much about his personality and shed light on his interactions with Angelico. Angelico, too, benefited

from slavery, and was at times a slaveholder. Though one might sympathize with Angelico's plight as a

woman, bemoan that Ormond could not find one more vote for her, and regret that Angelico's voice as

plaintiff is silenced in the court, the law at least attributed to Angelico the capacity to contract and

allowed her standing to sue, which i~ more than can be said of the slaves that both Isaac and Angelico

used to support the scheme around which Isaac's promise was made.

[Vol. 94:321

has ever taught the case

Our realization and the

looks at all. The answer

ton. Williston originally

lave been the mother of

7rksey in the 1920s and

;tappel." The ambiguity

l'S dual use of the case

udents' mirids, until the

Ironically, the opinion's

he case does not say, its

'oke students' analytical

n leaves open.

rksey v. Kirksey-the

he case so valuable in

because it is a good

ontract law. Kirksey's

Itroducing students to

lctS. The Kirksey story

, and the story we tell,

ished opinion and the

pproaches--other ways

e know it is a tale about

about race relations. 14

2006]

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

327

These themes are exactly what one would expect to find in Alabanla in 1840. Third,

the facts also suggest a philosophical comment about the mle of law and question

what the mle of law meant in America at the time. 15 Finally, there is contract law

history here relevant to the doctrinal development both of the bargain theory of

consideration (which appears fully fonned in 1845, before Holmes) and of promissory estoppel. But confining our work to anyone of these themes would have

diminished the value of our research to contract law teachers and students. Kirksey's

primary value is as a teaching case. Contract law teachers and students are interested

in all of these themes, and Kirksey's value in part lies in its being "about" all of them,

as well as its including the puzzles presented by the Kirksey opinion. Our research is

most valuable if we include facts relating to every facet from which Kirksey may be

approached.

So we begin tlle story. Part II of tlle Article focuses on Kirksey in the

nineteentll century. A significantly more complete description of tlle parties and

the underlying dispute is presented. Here, we explain why Isaac Kirksey invited

his sister-in-law to live near him only to displace her two years later. In Part III,

we review tlle litigation itself through the lens of the surviving trial and

appellate court records. Finally, Part IV tells what happened afterwards, first to

the parties and then to the Kirksey opinion. Part IV tllerefore focuses also on

Kirksey's use in legal education in the twentietll and early twenty-first centuries.

The Article reviews tlle case's appearance and use in casebooks and treatises.!6

Then tlle Article turns to Kirksey's use in classroom discussions and the extent

to which tlle historical record is consistent with pedagogical speculations about

the case.!? Along tlle way, Kirksey's puzzles are solved.

II. WHAT HAPPENED

A. THE PARTIES

1. Angelico Kirksey

tre for children-fourteen of

md died, his brother took up

dge and twelve male jurors.

tt instead should pay Isaac's

18 she is at the mercy of the

;er of the case was a woman,

1oI. We did not expect to see a

:lling in her son's home. We

not. She personally has no

~ to say for her. No plaintiff

'la. 357 (1843); Watkins v.

~reasing

wealth that allowed

with his slaves also reveal

.co. Angelico, too, benefited

e with Angelico's plight as a

gret that Angelico's voice as

he capacity to contract and

l1at both Isaac and Angelico

In tlle early 1800s, thousands of Scots-Irish families left North Carolina and

trekked westward through Tennessee. Many wound up in northern Alabama. !8

15. The "preference" laws enacted by Congress throughout the first half of the nineteenth century

(and discussed throughout this Article, especially in Part II), conferred an enormous economic benefit

on hundreds of thousands of American citizens who were squatting illegally on federal land. The

government rewarded them for their lawlessness, capitulating when it could not control its citizenry.

Just what "the rule of law" meant in this time period is uncertain. Isaac himself took a Holmesian "bad

man" approach to the law-Isaac being the bad man. See Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Path of the Law,

10 HARV. L. REv. 457 (1897); see infra text accompanying notes 64-84. In late 1842 or early 1843,

Isaac threatened to evict Angelico, an action we suspect also was overreaching and depended for its

efficacy on Angelico's powerlessness or incomplete lmowledge of her rights. See infra text accompany~

ing notes 196-98.

16. See infra Part Iv'B.

17. See infra Part rv:C.

18. DANIEL S. DUPRE, ThANSFORMING THE COTION FRONTIER: MADISON COUNTY, ALABAMA 1800-1840,

at 1 (1997).

328

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 94:321

John Connolly was a fairly typical member of this westward migration. As a

teenager, he fought in the American Revolution and held the rank of sergeant in

the Third Georgia Continental Line.!9 After the war, he married Obedience King

and started a family in North Carolina, where his fifth child, Angelico, the

plaintiff in Kirksey, was born in 1792.20 Although her name is spelled "Antillico" in the Kirksey opinion, the Court's spelling is aberrant. 2! She always went

by the name"Angelico," or within the family simply as "Gelico.',22

Not much is known about the Connolly family. Angelico was the fifth child,

but there were more to come. John eventually fathered twenty-eight children?3

His ninth child, Mary, was born in 1802. The family was very poor,24 and both

the father and Angelico were illiterate, which probably explains the many

spellings of her name. 2S The Connollys knew another Scots-Irish family, the

Kirkseys, in North Carolina,26 and Angelico apparently married Henry Kirksey

in North Carolina about 1813.27 Subsequently, the Connollys and the Kirkseys

left the state, traveled through Tennessee, and settled in Alabama. In 1819,

i i

J",

r

"

II

il

,

I

"I!

,'

,,'I:!:i'

"

19. MARJE ADELE KIRKSEY DARRON, FROM JAMESTOWN ONWARD: GENEALOGY OF DARRON, KmKSEY,--GRAVES, LEA, CONNALLY, HARPER, LoNG, AND WHITTINGTON AND ALUED LINES 141 (1980); LOUISE JULICH,

ROSTER OF REVOLUTIONARY SOLDIERS AND PATRIOTS IN ALABAMA 137-38 (1979~. We use the spelling

"Connolly," but John's name is also spelled "Connally." Variant spellings of a person's name were

common in the nineteenth century. See, e.g., infra note 21. In a society where many were illiterate, the

spelling of a name frequently was a phonetic approximation.

20. DARRON, supra note 19, at 141.

21. In the trial court, Angelico's name is spelled Antilico in the Writ and the Declaration but

Angelico in the Judgment. Trial Record, Kirksey v. Kirksey (Ala., Talladega Circuit Ct. Fall Term 1844);

in TALLADEGA CIRCUIT COURT RECORDS 1844-1846 [hereinafter Kirksey Trial Record]. A transcript of the

Kirksey Trial ReGOrd is fmmd in. ,Appendix L The Alabama Supreme Court files variously spell her

name "Angelica," "Angelic," "Antilico," and "Antillico." The "Antillico" spelling in the Court's

opinion comes from the parties' agreed statement of facts. Appellate Record, Kirksey v. Kirksey, No.

2598 (Ala., filed Dec. 18, 1844) [hereinafter Kirksey Appellate Record] (on file in the Alabama

Archives, Montgomery, Ala.). A copy of the Kirksey Appellate Record is found in Appendix IT. For

other aberrant spellings, see Letter [Tom Florence Holman to Bena Kirksey (Jan. IS, 1969) (copy on file

with authors) ("Anjelico" and "Anthilico"); Orphans Court Minutes 1839-1846, Marshall County, Ala.,

at 46 ("Gilico"); DARRON, supra note 19. at 69 ("Jellico").

22. See DARRON, supra note 19. at 69, 141-42.

23. JULICH, supra note 19, at 137-38.

24. When John Connolly's will was written in 1837, he said, "It is known that I have and possess but

very little of the wo~ld's goods and that I have a wife and Many Small Children." Last Will and

Testament of John W. Connolly, Probate Record IS, Madison County, Ala. The many small children

were by his second wife Eliza E. He noted that the children of his first wife still lived and tllat he had

raised ''them to Such Condition as they now. and that each of them is now able with and by honest

industry to Support themselves." Therefore he left all of his "little property" to his second family. Id.

25. Neither John Connolly nor Angelico could sign his or her name. Id.; Deed of Henry Kirksey &

Wife to David Moore (Feb. 18, 1839), Deed Record Book R, Madison County, Ala. The 1850 Census

states that Angelico could not "read or write." U.S. Census 1850, Madison County, Ala., available at

http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennialJdocuments/1850a-17.pdf.

26. DARRON, supra note 19, at 68.

27. The precise date and place of their marriage is not known. In 1880, their second son, John W.

Kirksey, see DARRON, supra note 19, at 69, said that he was sixty-four years old and was born in North

Carolina. U.S. Census 1880, Madison ,County, Ala. The 1830 Census listed John as being between the

ages of fifteen and twenty. U.S. Census 1830, Madison County, Ala. Another, older son is also listed. [d.

[Vol. 94:321

ward migration. As a

he rank of sergeant in

LITied Obedience King

child, Angelico, the

me is spelled "AntilOt. 21 She always went

ielico."Z2

;0 was the fifth child,

'enty-eight children?3

very poor,24 and both

y explains the many

cots-Irish family, the

larried Henry Kirksey

Uys and the Kirkseys

o Alabama. In 1819,

.LOGY OF DARRON, KIRKSEY,

; 141 (1980); LOUISE JUL1CH,

1979~. We use the spelling

s of a person's name were

~re many were illiterate, the

it and the Declaration but

Circuit Ct. Fall Tenn 1844),

Record]. A transcript of the

files variously spell her

spelling in the Court's

lrd, Kirksey v. Kirksey, No.

.] (on file in the Alabama

2006]

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

329

Henry and Angelico lived on Hobbs Island, about twenty miles from Huntsville

in Madison County, Alabama. 28 Henry purchased farm land there from the

federal government?9 Henry also bought a farm a few miles away, off the

island, next to the Connollys' farm. 3o By 1830, Henry and Angelico had nine

children. 3l Over the next ten years, they had five more. 32

The 1820s and 1830s were boom times in Alabama, but the Panic of 1837

ended this era of speculation and prosperity.33 The state's monetary and banking

system was based primarily upon credit, and capital ventures were financed by

debt. Most money took the form of banknotes issued by banks with scant specie

reserves. A confluence of international and national policies brought the inordinate reliance upon debt and grossly inflated paper currency to a halt. In

Alabama and elsewhere, people began demanding payment of debts in gold or

silver rather than banknotes, and the economy collapsed. The banks suspended

specie disbursements, and Alabamans who had significant debts when the Panic

struck were simply unable to meet their contractual obligations. The situation

was so bad that in the summer of 1837 the state legislature passed a statute

approving the banks' suspension of specie payments. More significantly, the

statute rescheduled the payment of debts to the state-controlled banks, including

the Branch Bank in Huntsville. 34

The Panic probably prompted Angelico and Henry to move to another county.

Hemy owed money to the Branch Bank in Huntsville, and the 1837 statute

extended his debt by three years with three progressively larger annual payments. 35 In February 1839, a month before the second payment was due,

Angelico and Henry sold 240 acres of l:jlld in Madison County for the sum of

$1700 and moved to neighbOling Marshall County, where they apparently

Llrt

0"

found in Appendix It. For

:Jan. 15, 1969) (copy on file

846, Marshall County, Ala.,

that I have and possess but

I Children." Last Will and

l

t. The many small children

e still lived and that he had

w able with and by honest

to his second family. Id.

; Deed of Henry Kirksey &

mty, Ala. The 1850 Census

1 County, Ala., available at

, their second son, John W.

: old and was born in North

Jolm as being between the

" older son is also listed. [d.

28. DARRON, supra note 19, at 69.

29. MARILYN DAVIS BAREFIELD, OLD HUNTSVILI:..E LAND OFFICE RECORDS & MILITARY WARRANTS

1810-1854, at 129 (1985).

30. Patent Records, Huntsville No. 2342, Isaac Kirksey, assignee of Henry Kirksey (May 20, 1828)

(on file at the National Archives, Washington, D.C.) (showing that Henry purchased the land in 1819

and made payments until 1826, then assigned the land to Isaac in 1827 before the patent issued); Patent

Records, Huntsville No. 2344, Isaac Kirksey, assignee of John Connally, assignee of David Connally

[sic] (May 20, 1828) (on file at the National Archives, Washington, D.C.) (showing that David

Connolly purchased property just to the north of Henry's plot in 1814 and assigned the property in 1814

to John Connolly (attested to by Thomas Connolly, JP), that John Connolly made payments until 1826,

then assigned the land to Isaac Kirksey in 1827 before the patent issued). Both of these records show

adjustments of Henry Kirksey's and Jolm Connolly's payment amounts and due dates following the

Huntsville land market crash of 1819-1820. See, e.g., Act for the Relief of Purchasers of Public Lands

Prior to the First Day of July, Eighteen Hundred and Twenty, ch.12, 3 Stat. 612 (1821).

31. U.S. Census 1830, Madison County, Ala.

32. U.S. Census 1840, Marshall County, Ala.

33. See WILLIAM BRANTLEY, BANKING IN ALABAMA 1816-1860, at 337-59 (1961); WILLIAM ROGERS ET

AL., ALABAMA: THE HISTORY OF A DEEP SOUTH STATE 138-425 (1994).

34. An Act To Extend the Time of Indebtedness to the Bank of the State of Alabama and to Its

Branches, 1837 Ala. Acls9, 9-10, § 2.

35. See id. The first payment was 25% of the principal, and the second two payments were 37.5%

each. [d.

330

I

,;1.

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[VoL 94:321

engaged in cotton farming on leased land. 36 At this time they had nine male and

three female children living with them. 3? The next year the loan extensions

imposed by the legislature expired, and the Branch Bank filed hundreds of

lawsuits against defaulting debtors. In August 1840 alone, seventy-eight default

judgments were entered in the Bank's favor, including one for $268.65 against

Henry Kirksey.38 In October the court issued a writ to execute upon Henry's

property,39 but to no avaiL The Kirkseys were no longer in the county, and the

Sheriff of Madison County had no authority to cross the line into Marshall

County.40

In any event, Henry died sometime in August 1840,41 soon after the default

judgment was entered. In early September, Angelico and a Kirksey relative

were appointed administrators of Henry's estate, but the court revoked their

appointroent three weeks later for failure to post a bond, and Angelico's second

son, John W. Kirksey, was appointed in their stead:2 Eventually the son's

appointment was also revoked for failure to post a bond. 43 Although the estate

had significant assets, including a crop of cotton," when the estate was finally

settled two years after Henry's death, not much was left. The Branch Bank and

other creditors received fourteen cents on the dollar.45 Perhaps the family looted

the estate. We do not know.

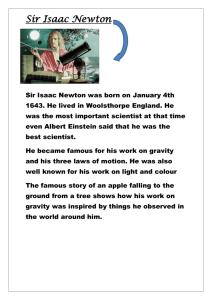

2. Isaac Kirksey

While Henry and Angelico were encountering financial hardship, Henry's

brother Isaac46 fared far better-first in Madison and then in Talladega County.

Isaac is a familiar figure in American life. He was a working-class man who,

36. Deed of Henry Kirksey & Wife to David Moore, supra note 25. The Kirksey decision recites that

Angelico "resided on public land, under a contract of lease." Kirksey v. Kirksey, 8 Ala. 131, 131

(1845). TIlere is no record of any Kirksey owning land in Marshall County during the 1830s and 1840s.

See BAREFIELD, supra note 29, passim; MARGARET MATTIfEWS COWART, OLD LAND RECORDS OF MARSHALL

COUNTY, ALABAMA (1988).

37. U.S. Census 1840, Marshall County, Alabama.

38. Madison County Court Minute Book 1840-1841, Aug. Term 1840, Nos. 5966-6044, Madison

County, Ala.; Branch Bank v. Henry Kirksey, Madison County, Ala.

39. Madison County Court Execution Docket 1830-1845, Aug. Term 1840, No. 6010/5339, Madison County, Ala.

40. See Jones v. Bll1Cter, 41 So. 781, 782 (Ala. 1906); Sheriffs and Constables, in 43 CENTURY

EDmoN OF THE AMERICAN DIGEST § 101 (1903).

41. The initial application for letters of administration for Henry's estate was on September 5, 1840.

Orphaps Court Minutes 1839-46, Marshall County, Ala., at 46.

42. [d. at 46-47, 56.

43. [d. at 74, 79. The court entered a judgment against John W. Kirksey in respect of any property

sold subject to a credit for payments made. [d. at 79. Ultimately, the court rendered a judgment in the

amount of $769.95. Marshall County Probate Court Minutes 1839-1844, Marshall County, Ala., at 209.

44. Orphans Court Minutes 1839-46, Marshall County, Ala., at 96, 105.

45. Final settlement of the estate of Henry Kirksey (Nov. 24, 1842), Marshall County Probate Court

Minutes 1839-1844, Marshall County, Ala., at 209-12.

46. Although his full name was James Isaac Kirksey, he always went by his middle name and never

included his first name in his signature. DARRON, supra note 19, at 76. Similarly, his brother Henry was

actually named William Henry, but like his brother he dropped his first name. [d. at 69.

[Vol. 94:321

:hey had nine male and

ar the loan extensions

ank filed hundreds of

~, seventy-eight default

ne for $268.65 against

execute upon Henry's

. in the county, and the

the line into Marshall

2006]

THE STORY OF KlRKSEY V.

KlRKSEY

331

during a lifetime of constant wheeling and dealing, managed to amass a sizeable

fortune. Nevertheless, when he died, he was still desclibed as "a laboring man, a

Blacksmith by trade.,,·7 Isaac was "tall, very fair and fine 100king.,,·8 He was

Scots-Irish and reputedly spoke in a "Scotch brogue.,,·9

soon after the default

md a Kirksey relative

Ie court revoked their

and Angelico's second

. Eventually the son's

.43 Although the estate

1 the estate was finally

The Branch Bank and

rhaps the family looted

cial hardship, Henry's

n in Talladega County.

)rking-class man who,

~

Kirksey decision recites that

v. Kirksey, 8 Ala. 131, 131

,during tlle 18308 and 18408.

) LAND RECORDS OF MARSHAlL

), Nos. 5966--6044, Madison

1840, No. 6010/5339, Madi-

Constables, in 43 CENTURY

~e

was on September 5, 1840.

Isaac Kirksey (by permission, Robert R. Darron)

Isaac was born in North Carolina and, as a boy, migrated across Tennessee

to Alabama with the rest of the Kirksey family and the Connollys. In 1821,

Isaac married Angelico's sister, Mary Connolly, and already had his own

"smith's shop."sO He was an ambitious man with an eye out for any

opportunity to make money. As a young man, he began buying and selling

land in Madison County.5l He eventually bought land from Henry and the

ey in respect of any property

It rendered a judgment in the

vlar8hall County, Ala., at 209.

arshall County Probate Court

Iy his middle name and never

lilarly, his brother Henry was

(le. [d. at 69.

47. Kirksey v. Kirksey, 41 Ala. 626, 630 (l868) (testimony of James Montgomery, who had known

Isaac since 1835).

48. DARRON, supra note 19, at 76.

49. Letter from Florence Holman to Lunda Brown (Aug. 13, 1965) (on file in the Kirksey File at the

Clayton Library, Hous~on, Tex.).

50. 124 ALABAMA RECORDS 50, 54 (Kathleen Paul Jones & Pauline Jones Gandrud camps., 1961).

51. See 103 id. at 76:

332

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 94:321

Connollys.52 But he did not restrict himself to land transactions. He also

bought and sold human beings. In 1830, he owned thirteen slaves. 53

By the early 1830s, Isaac and his wife were well established in Madison

County. In 1830, he was thirty-three, and Mary (whom everyone called Nancy)

was twenty-eight. 54 At the time, they had three boys and two girls. 55 He was

appointed Justice of the Peace in 1832 and served in that capacity for the rest of

his life. 56 In 1830 he and four other men bought "two acres for the use of the

Methodist Church.,,57

But Isaac and Nancy did not stay in Madison County. In the 1820s much of

central Alabama was ruled by the Creek Indians, but in 1832 the Creeks ceded

the last of their land to the federal government, and part of this cession became

Talladega County.58 At the same time, the first cotton gin in Alabama was built,

and cotton quickly became the state's most important crop.59 Isaac saw the

enormous agricultural potential of the new counties. He sold his property in

Madison County"° and in 1834 moved his family to Eastaboga in the northern

part of Talladega County, where he established a plantation. He called his new

home Locust Grove. 61

Isaac was not a simple farmer who tilled his own land. Locust Grove was a

cotton plantation, and most of the work was done by slaves. In Alabama and

elsewhere, an individual who owned fifty or more slaves was a large planter,62

and twenty slaves was "roughly a minimum for the plantation method.,,63 By

1840 Isaac was almost a large planter, with forty-seven slaves, and in 1850 he

owned fifty human beings. 6' His plantation at this time was not one large,

contiguous stretch of land. 65 Generally an Alabama plantation of that period

52. See supra note:i\O.

53. U.S. Census 1830, Madison County, Ala., at 115; see also 201 ALABAMA RECORDS, supra note 50,

at 26 (referring to page 359 of Madison County Deed Book H to show that Isaac bought a slave in

1822); Hinton v. Isaac Kirksey (Ala. ell. 1833), in 138 ALABAMA RECORDS, supra note 50, at 88

(showing that Isaac traded a male slave for a woman and her children).

54. DARRON, supra note 19, at 76, 141.

55. U.S. Census 1830, Madison County, Ala.

56. 1 ALA. SEC. OF STATE, COMMISSION REGISTER 444 (1819-1832) (on file at the Ala. Dep't of

Archives & History, Montgomery. Ala.); 2 id. at 322, 326 (1832-1834).

57. 71 ALABAMA RECORDS, supra note 50, at 62.

58. E. GRACE JEMlSON, HISTORIC TALES OF TALLADEGA 65-70 (1959).

59. THOMAS PERKINS ABERNETHY, TH:E FORMATIVE PERIOD IN ALABAMA 1815-1828, at 30-32 (rev. ed.

1965).

60. Deed from Isaac Kirksey and wife Mary to Jo1m E. Taylor (Feb. 2, 1833), in 124 ALABAMA

REcORDS, supra note 50, at 60; Deed from Isaac Kirksey and wife Mary to David Moore (Aug. 6, 1836),

in 124 id. at 64; Deed [TOm Isaac Kirksey to Levi Hinds (Oct 7, 1835), in 124 id. at 68.

61. DARRON, supra note 19, at 76. He bought his land in January 1834, a few weeks after the Federal

Land Office opened. BAREFIELD, supra note 29, at v, 9.

62. JAMES SELLERS, SLAVERY IN ALABAMA 40 n.52 (1950); accord Joseph Menn, The Large Slaveholders of the Deep South, 1860, at v (1964) (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas Austin).

63. J. Mu.LS THORNTON, POLmcs AND POWER IN ASLAVE SOCIETY: ALABAMA 1800-1860, at 63 (1978).

64. U.S. Censns 1840, Talladega County, Ala.; U.S. Censns 1850, Talladega County, Ala.

65. See infra text accompanying notes 104-28.

r

1

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

[Vol. 94:321

ransactions. He also

en slaves. 53

tablished in Madison

eryone called Nancy)

I two girls. 55 He was

apacity for the rest of

res for the use of the

[n the 1820s much of

g32 the Creeks ceded

f this cession became

.n Alabama was built,

:rop59 Isaac saw the

sold his property in

,boga in the northern

m. He called his new

Locust Grove was a

.ves. In Alabama and

was a large planter,62

tation method.,,63 By

laves, and in 1850 he

~ was not one large,

Itation of that period

2006]

tl

file at the Ala. Dep't of

15-1828, at 30-32 (rev. ed.

2, 1833), in 124 ALABAMA

'avid Moore (Aug. 6, 1836),

~4 id. at 68.

few weeks after the Federal

lIenn, The Large Slavehold

tion, University of Texas w

1800-1860, at 63 (1978).

,ga Couuty, Ala.

IA

333

was limited to the distance a man could walk in one hour from the slave

quarters. Large planters often owned several, noncontiguous plantations, with

lhe satellite plantations being supervised by sons or overseers. 66 In addition to

growing cotton, Isaac had many olher commercial irons in the fire. In 1835 he

bought 4000 acres of land in the Mexican state of Texas. 67 He "was a man of

means, was very economical; [and] was in the habit of loaning money."68 Isaac

also "established a big merchant mill, tannery, wagon factory, and factories for

the manufacture of harnesses, shoes, and other lealher goods."69

In lhe early 1850s, Frederick Law Olmstead toured Alabama an(i subsequently wrote a colorful description of Alabama planters like Isaac Kirksey.

Olmstead reported that they "were usually well dressed, but were a rough,

com:se style of people, drinking a great deal, and most of lhe time under a little

alcoholic excitement.',7o They were "[n]ot sociable, except when lhe topics of

cotton, land, and negroes were started; interested, however, in talk about lhe

lheaters and the turf; very profane.'m Moreover, they often showed "lhe

handles of concealed weapons about lheir persons, but [lhey were] not quarrelsome, avoiding disputes and altercations, and respectful to one anolher in forms

of words." n

Olmstead's portrait of a typical Alabama planter rings true in the case of Isaac

Kirksey (certainly Isaac is well-dressed in lhe only known photograph of

him73 ), but Olmstead clearly does not paint a complete portrait of the man.

There are indications lhat within his family he was very generous. He apparently was "an indulgent father,"7' and he believed in the value of education. 7s

At lhe same time, there is evidence of a darker side to Isaac's character. He was

66.

supra note 50,

hat Isaac bought a slave in

lRDS, supra note 50, at 88

MA RECORDS,

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

ROGERS-ET -AL.pyupra-llote 33,at-9_~97..

67. DARRON, supra note 19, at 77-78. This land was in what was to become Anderson County, Texas.

In 1860 Isaac bought an additional 1000 acres in NavalTO County, Texas. [d.

68. Kirksey v. Kirksey, 41 Ala. 626, 632 (1868) (testimony of John C. Walker). For charges of usury,

see Jones v. Kirksey, 10 Ala. 579 (1846); Kirksey v. Jones, 7 Ala. 622 (1845).

69. DARRON, supra note 19, at 97 (quoting an 1895 Dallas Moming News article about Isaac's son);

see also Kirksey v. Fike, 27 Ala. 393 (1855) (litigation over tannery); Probate Court Minutes, vol. I, at

199 ("Kirksey's Mill"), Talladega County, Ala. (1867-69).

70. 1 FREDERICK LAW OLMSTEAD, THE COTTON KINGDOM 276 (1861). An earlier Alabama visitor from

the North recorded that "the people [are] devilish. Duelling and fighting the chief diversions, [g]ambling and drinldng pastimes, and an uninterrupted, conunon intercourse with the negroes the virtue of

all the men." Luaus BIERCE, TRAVELS IN THE SOUTIILAND 1822-1823, at 1, 99-100 (G. Knepper ed.,

1966). The context of Bierce's statement makes it clear that by "intercourse" with the "negroes," he

meant sexual intercourse. See id.

71. 1 OLMSTEAD, supra note 70, at 276-77.

72. Id. at 277.

73. See supra photograph at text accompanying note 50.

74. DARRON, supra note 19, at 77.

75. In addition to serving on the board of directors of the Eastaboga Academy, see JEMISON, supra

note 58, at 277, Isaac insisted that all of his sons and daughters go to school. At least the 1850 Census

states that his school age children were attending school. U.S. Census 1850, Talladega County, Ala. He

sent one of his sons to an "eastern university." DARRON, supra note 19, at 88. It must be said, however,

that the 1865 inventory of Isaac's estate lists only "1 Lot Books" valued at ten dollars. Talladega

County \VilIs & Inventories, vol. C, at 95, Talladega County, Ala.

334

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 94:321

a "velY economical,,76 man, and outside the family his constant striving for

wealth may have taken him down immoral paths. There is some evidence that

his "habit of lending money"n involved USury.78 Isaac was also well known to

the Alabama judiciary. He appeared as a plaintiff as early as 182879 and never

seems to have slaked his thirst for litigation. From 1845 to 1856, the Alabama

Supreme Court published eight opinions in cases involving Isaac. 8o

Finally, Isaac Kirksey owned slaves. Some might say that he was just a man

of his times, and that in choosing to become a slaveholder, he was simply doing

what everyone else was doing. Perhaps-but the moral dimensions of slavery

had been fully elaborated in nineteenth-century America. Many rejected the

institution as immoral, and many embraced it. Isaac Kirksey was a "very

economical" man who embraced slavery and made a fortune from it.

Even if the general moral problem of slavely is set to one side, there is

evidence that Isaac was more abusive than other slaveholders. In the eal"ly

l830s, a woman that he claimed to own sued him for her and her children's

freedom. Edy Hinton alleged that she was in fact a "free woman of color [and]

daughter of a free mulatto woman.,,8! She and her eight children were kidnapped in Tennessee and sold as slaves to Isaac in Alabama. If these claims

were Due,82 Isaac should have released her and her farnily,but a "very economi~

cal" man like Isaac Kirksey might have been unwilliug to lose the value of his

bargain. Isaac's "economical" ways apparently influenced the way he treated his

slaves. In 1861 his oldest son, Albert O. Kirksey, offered to buy one of Isaac's

slaves "who was then a lUuaway.,,83 Isaac responded tllat "he would not sell the

negro, as the balance of his negroes would run away if he did, just to be sold.,,84

In Isaac's eyes, his slaves would have preferred to be owned and controlled by

someone other than himself.

Isaac's economic welfare steadily improvedtlrroughout the l830s, but the

end of the decade brought a double tragedy. On October 13, 1839, his wife

76. See supra note 68 and accompanying text

77. See supra note 68 and accompanying text.

78. See supra note 68.

79. Kirksey v. Weaver (Ala. eh. 1828), in 97 ALABAMA RECORDS, supra note 50.

80. Kirksey v. Jones, 7 Ala. 622 (1845); Kirksey v. Kirksey, 8 Ala. 131 (1845); Kirksey v. Mitchell,

8 Ala. 402 (1845); Jones v. Kirksey, 10 Ala. 579 (1846); Jones v. Kirksey, 10 Ala. 839 (1846);

Montgomery's Ex'r v. Kirksey, 26 Ala. 172 (1855); Kirksey v. Fike, 27 Ala. 383 (1855); Kirksey v.

Fike, 29 Ala. 206 (1856). Other litigation never reached that level. See, e.g., supra notes 81-82 and

accompanying text (discussing the Hinton case); Notice, Isaac Kiksey [sic] v. Wm. Montgomery &

Hugh Montgomery, TALLADEGA (Ala.) WATCHTOWER, Aug. 16, 1843. Given Isaac's litigiousness, it is

fitting that his heirs took the settlement of his estate to the Alabama Supreme Court. Kirksey v. Kirksey,

41 Ala. 626 (1868).

81. Hinton v. Kirksey (Ala. Ch. 1833), in 138 ALABAMA REcORDS, supra note 50, at 88.

82. The suit was not resolved on the merits. All we have is a cryptic statement in the judicial

records: "Came the parties by counsel and state they will not further prosecute." [d.

83. Kirksey v. Kirksey, 41 Ala. 626, 632 (1868) (eyewitness testimony of John C. Walker).

84. rd.

~.

I

I

I

I

\

[Vol. 94:321

constant striving for

is some evidence that

IS also well known to

, as 182879 and never

to 1856, the Alabama

; Isaac. so

!at he was just a man

he was simply doing

limensions of slavery

I. Many rejected the

illksey was a "very

te from it.

to one side, there is

holders. In the eal"ly

er and her children's

~oman of color [and]

It children were kid,ama. If these claims

but a "very economilose the value of his

he way he treated his

to buy one of Isaac's

he would not sell the

lid, just to be sold.,,84

led and controlled by

t the 1830s, but the

r 13, 1839, his wife

r

2006]

Nancy died from "a lingering illness.,,85 Isaac was not long in mourning. Five

months later he remarried-this time to Sarah Edwards. 86 Sarah was twentyseven years old, and she and Isaac subsequently had five children. 87 Shortly

after Isaac's remarriage, he learned of his brother Henry's death in Marshall

County. Isaac inunediately resolved to invite his sister-in-law and her children

to move down to Talladega County and live near him.

B. THE CONTROVERSY: WHY INVITE AND WHY EVICT?

On October 10, 1840, eight months after his remarriage, Isaac wrote Angelico

the following letter. Most of it was later recited by the Alabama Supreme Court

in Kirksey v. Kirksey. We have italicized the omitted portion.

Dear Sister Antillico [sic] - Much to my mortification, I heard that brother

Henry was dead, and oue of his children. I know that your situation is one of

grief and difficulty. You had a bad chance before, but a great deal worse now.

I should like to come and see you, but cannot with convenience at present. I

am Itot well at prese1tt, my family has beelt gelterally well, all but myself altd

my youltgest SOIt. We have Itot bee1t very sick. The health of the COUltty is

tolerably good at preseltt. I should like to kltow your situation. I do not know

whether you have a preference on the place you live on or not. If you had, I

would advise you to obtain your preference, and sell the land and quit the

country, as I understand it is very unhealthy, and I know society is very bad. If

yon will come down and see me, I will let you have a place to raise your

family, and I have more open land than I can tend; and on account of your

situation, and that of your family, I feel like I want yon and the children to do

welL 88

Withiri"a month or two" after recelVlng this letter, Angelico brought her

family-herself and as many as nine children89-down to Talladega. 9o Isaac

85.

fte 50.

1845); Kirksey v. Mitchell,

"ey, 10 Ala. 839 (1846);

la. 383 (1855); Kirksey v.

g., supra notes 81-82 and

cJ v. Wm. Montgomery &

Isaac's litigiousness, it is

Court. Kirksey v. Kirksey,

)te 50, at 88.

~ statement in the judicial

e." Id.

fohn C. Walker).

335

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

CAROLYN

LANE LUTIRELL, EARLy TOMBSTONE REcORDS

OF TALLADEGA

COUNTY, ALABAMA 32 (1973)

(quoting the inscription on Nancy's tombstone: "She had been an exemplary member of the Methodist

Church for more than ten years. She bore up under a lingering illness for many months but was never

heard to murmur but often heard to say, not my will but thine be done, Oh Lord").

86, Letter to Mrs. DJ. (Christine Kirksey) Rndder (Sept. 11, 1970) (taken from St. Clond Co.• Ala.,

Marriage Book 1, p. 138) (on file in the Kirksey File, Clayton Library, Houston, Tex.).

87. DARRON, supra note 19, at 106.

88. Bill of Exceptions, in Kirksey Appellate Record, supra note 21; see also Kirksey v. Kirksey, 8

Ala. 131, 131-32 (1845).

89, She likely brought to Locust Grove at least eight children, including the following: Louisa, age

16; Mary Jane, age 10; Edwin, age 9; Eliza, age 7; Andrew, age 6; and Granville, age 2. Compare U,S.

Census 1830, Madison County, Ala" U.S. Census 1840, Marshall County, Ala., at 36, ami U.S. Census

1850, Madison County, Ala., at 395, with DARRON, supra note 19, at 69-73. Besides these six, Angelico

had with her in 1840 at least five other children, two of whom likely were young and dependent. The

1840 Census lists six others still living with Henry and Angelico when the census was taken: two males

age 20-30, one male age 15-20, two males age 10-15, and one more male age 3-5. One of these died

when Henry died: Isaac's letter refers to the death of one of Henry's children, See Kirksey, 8 Ala, at

132. TIlis was likely after the census, which itself lists Henry. U.S. Census 1840, Marshall County, Ala.

336

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 94:321

gave her houses to live in and land to tend9' which she and her family cultivated

for their own support. 92

In all likelihood, Isaac's motives in writing this letter were mixed. He was

extending a helping hand to the wife and children of his recently deceased

brother and the sister of his recently deceased wife. He gave his deceased

brother's name to the first child of his second marriage. 93 At the same time,

however, Isaac was an "economical" man, and he appears to have had economic

reasons for Angelico's presence on his "open land." Understanding Isaac's

motives requires some understanding of land acquisition in antebellum Alabama, however: how Isaac acquired his land, and on what land he placed

Angelico and her family.

Isaac Kirksey was one of the first white men to own land in Talladega

County. The County itself was formed in December 1832, just nine mQnths after

the Creek cession,94 before any settler held title to land there. 9s Though the

1832 treaty reserved some land for the Creeks, much of the cession passed into

U.S. Government hands free of native claims. After taking a census of the

Creeks, conducting a quick land survey, and allowing time for Creek natives to

choose specific parcels pursuant to the treaty, the federal government began

selling the remaining Talladega land to settlers in January 1834.96 Under the Act

of April 24, 1820, a minimum price of $1.25 per acre was established for all

federallands. 97 Over ninety percent of land sold by the federal government in

antebellum Alabama went for not more than $1.25 per acre. 9S Of course, land

was not always available at that price. In 1837, just prior to the Panic,

Thus, five were left. But two of the three younger sons, and perhaps three if one of the older sons died

with Henry, may well have accompanied her to Locust Grove. That would indicate that Angelico

brought eight or nine children.

90. See Kirksey, 8 Ala. at 132.

91. Id.

92. The appellate record states that Isaac "gave her good open land to cultivate." Bill of Exceptions,

in Kirksey Appellate Record, supra note 21 (counsel for both parties stipulated to the statement of facts

in the Bill of Exceptions). The Bill of Exceptions also notes that there was some dispute whether Isaac,

had Angelico moved to the house in the woods, as Isaac later asked her to do, "still proposed to allow

[Angelico] to cultivate the same cleared land," id., indicating that she did indeed cultivate it. Angelico's

Declaration states that Isaac provided land "for the purpose of cultivation to support herself & family."

Declaration, in Kirksey Trial Record, supra note 21.

93. DARRON, supra note 19, at 107.

94. JEMISON, supra note 58, a1 79 (noting that the act creating the counties was approved by the

legislature iIi January 1833). The bill in the Alabama legislature was drawn up by Green T. McAfee. [d.

95. [d. at 65-70, 83 ("[T]here were no public lands offered for sale in 1833."); :MARy ELIZABETH

YOUNG, REnSKINS, RUFFLESHIRTs, AND REDNECKS, maps 13 & 14 (1961).

96. JEMISON, supra note 58, at 71; YOUNG, supra note 95, at 74, 179.

97. Act of Apr. 24, 1820, ch. 51, § 3, 3 Stal. 566, 566. This price was a change from the two dollar

per acre price established by the Act of May 18, 1796, and retained by subsequent statutes until 1820.

See, e.g., Act of May 10, 1800, ch. 55, § 5, 2 Stat. 73, 75.

98. YOUNG, supra note 95, at 1'15-76.

[Vol. 94:321

her family cultivated

vere mixed. He was

s recent!y deceased

gave his deceased

3 At the same time,

) have had economic

1derstanding Isaac's

in antebellum Ala'hat land he placed

1 land in Talladega

1st nine months after

there. 9S Though the

, cession passed into

ng a census of the

for Creek natives to

. government began

l34. 96 Under the Act

s established for all

ieral government in

e. 98 Of course, land

prior to the Panic,

one of the older sons died

ld indicate that Angelico

ivate." Bill of Exceptions,

d to the statement of facts

me dispute whether Isaac,

::l, "still proposed to allow

led cultivate it. Angelico's

mpport herself & family."

ties was approved by the

) by Green T. McAfee. [d.

1833."); MARy EUZABETIl

lange from the two dollar

:quent statutes until 1820.

2006]

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V. KIRKSEY

337

speculators sold land for as much as $39 per acre,99 and federal prices would

have risen with the market. The federal government initially offered land at

auction, but if no sale occurred, the land could be classified as "offered" and

later sold in a "private sale" for not less than $1.25 per acre. 100 Whereas

pre-1820 law allowed sales on credit (including land in Alabama around

Huntsville when Henry and Angelico arrived there),'01 the Act of 1820 forbade

credit sales. 102

Congress established land offices in the territories. 103 Land in Talladega

County was sold through the Mardisville Land Office, located in th~ County

itself. There, on January 18, 1834, Isaac Kirksey purchased 160 acres from the

federal govemment. 104 Eighty of these he soon sold to someone else. lOS On

January 29, Isaac bought another eighty acres from the federal government. '06

At about the same time, he purchased an additional 240 acres from others,

including land speculator Elijah Moore Driver, who had arrived shortly before

Isaac. 107 Patents were later issued to Isaac for the 400 acres that he retained. 108

All of this land was contiguous, or a short walk away, in trne plantation style.

99. JEMISON, supra note 58, at 106. In the recession following 1837, when cotton prices spiraled,

land prices followed. Id. at 106-09. But to those with preemption rights, as discussed later in this

section, land was always available for the minimum price.

100. Act of Apr. 24, IS20, ch. 51. § 3.3 Stat. 566, 566 (as to the price); Land Ordinance of 1785

(reprinted in 28 J. CONTINENTAL CONGo 375 (Jon Fitzpatrick ed, 1933)); PAUL W. GATES & ROBERT W.

SWENSON, HISTORY OF PUBLIC LAND LAW DEVEWPMENT 127 (1968).

101. E.g., Act of May 18,1796, ch. 29. § 7, 1 Stat. 464, 467-68 (allowing sales on credil); see also

GATES & SWENsoN,;.$upxanote,lOO"at-121d3. Henry and Angelico, in fact, purchased land on credit in

1819. Henry paid the last installment in 1826. Ironically, after making the last payment, he assigned his

rights in the land to Isaac, to whom a patent was eventually issued. Patent Records, Huntsville No.

2342, Isaac Kirksey, assignee of Henry Kirksey (May 20, 1828) (on file at the National Archives,

Washington, D.C.).

102. Act of Apr. 24, 1820, ch. 51, § 2, 3 Stat. 566, 566 (forbidding sales on credit).

103. See, e.g.• Act of Mar. 3, 1803, ch. 27, § 4. 2 Stat. 229, 230 (establishing land offices for sale of

lands in the "Mississippi Territory," which included what would later become Alabama, and directing

that sales be accomplished in the same manner as in other land offices elsewhere); Act of May 10, 1800,

ch. 55, §1, 2 Stat. 73, 73 (establishing offices in what would later become Ohio).

104. Tract Book of the Mardisville Land Office, Township 17, Range 6 E., at 109 (cert. #496), 112

(cert. #503).

105. Patent issued to Daniel Huff Norwood, assignee of Isaac Kirksey, Mardisville, cert. #503, Ser.

#AL0960_.495 (Oct. 20, 1835), available at http://www.glorecords.blm.gov (Bureau of Land Management's General Land Office Records).

106. Tract Book of ille Mardisville Land Office, Township 17. Range 6 E., at 109 (cert. #663).

107. Tract Book of ti,e Mardisville Land Office, Township 17, Range 6 E., at 109 (cert. #497, #498),

112 (cert. #388).

108. Patent issned to Isaac Kirksey, Mardisville, cert. #388, Ser. #AL0960_.380 (Oct. 20, 1835);

Patent issued to Isaac Kirksey, Mardisville, cert. #496, Ser. #AL0960_.488 (Oct. 20, 1835); Patent

issued to Isaac Kirksey, Mardisville, cert. #497, Ser. #AL0960_.489 (Oct. 20, 1835); Patent issued to

Isaac Kirksey, Mardisville, cerl. #498, Ser. #AL0960_.490 (Oct. 20, 1835); Patent issued to Isaac

Kirksey, Mardisville, celt. #663, Ser. #AL0970_.156 (Aug. 1, 1837). These patents are also available

at the Bureau of Land Management's General Land Office Records website, supra note 105.

~

...

,-338

THE GEORGETOWN LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 94:321

Isaac may in fact have added to this acreage,109 but not all deeds from this

period were recorded.!10 Later maps show Isaac's 400 acres at the core of a

larger plantation. 11 ! In any event, Isaac began life in Talladega as a fairly large

landholder. He owned some of the better land in the county.11Z And he was

hungry for more. As previously noted, in 1835, he purchased thousands of acres

in Texas.

Isaac Kirksey, however, did not always buy land in order to cultivate it. He

bought and sold land profitably around Huntsville, and when he first came to

Talladega, he saw land speculators such as Elijah Moore Driver and Charles

White Peters in action. 113 In fact, he bought eighty acres from Driver to

compose his original plantation. 114 Isaac, too, began to buy and sell land. In

March of 1835, he purchased 320 acres five miles to the west of his Talladega

plantation. 115 He sold this land in 1836. 116 Surviving records indicate that

although he maintained and enlarged his central plantation, he sold unconnected

property that he obtained in Talladega for profit, at least until 1843.

In 1837, Isaac lent money to a neighbor, Robert Lane. ll7 In exchange, Isaac

109. In 1838, Isaac added to this plantation about thirty acres on the north bank of the Chbcolocho

Creek. Indenture from Robert McLane to Isaac Kirksey (May 4, 1838), Talladega County Property

Records, bk. C, at 262 (recorded Dec. 10, 1839).

110. For instance, Isaac transferred 320 acres in 1836 to Uriah Hussaby or Hussady in a deed that

was not recorded. Indenture from Isaac Kirksey to Green T. McAfee, Talladega County Property

Records, bk. D, at 596-98 (recorded Nov. 9, 1843).

111. Map of Talladega County, Ala. (Birmingham: Bethel W. Whitson, c.1930), bttp://alabamamaps-

.ua.edulhistoricalmaps/cQunties/talladega.html (last visited July 19. 2005). This map refers to the

plantation as Indian Hill Plantation, and lists its size as 1,052.22 acres. [d. Kirksey family genealogists

believe that Indian Hill is a later name for Locust Grove. Notes of Verolean Kirksey on DARRON, supra

note .19,.at 76 (copy on. Jile"_with. authors). "The plantation remains mostly fannland today, but the

Talladega· Municipal Airport sits on its northwestern comer, and the NASCAR Talladega Super

Speedway was built just off of what property records show was its western border.

112. Land at the time was selling for between $1.25 and $2.00 per acre, but Isaac paid $3.17 per acre

for one eighty-acre parcel and $6.60 per acre for another. Tract Book of the Mardisville Land Office,

Township 17, Range 6 E., at 109 (cert. #498 ($3.i7) & #496 ($6.60)).

113. Tract Book of the Mardisville Land Office, Township 17, Range 6 E., at 109, 112 (recording

numerous sales to Driver and Peters on January 18 and 29, 1834, the same days that Isaac purchased);

Tract Book of the Mardisville Land Office, Township 16, Range 6 E., at 18-20 (same). Driver was very

successful in Talladega, as he had been in Huntsville. YOUNG, supra note 95, at 165 (reporting that

Driver purchased 96,269 acres in Madison County, Alabama, and Yalobusha County, Mississippi, in the

period 1836-54); Mark Jordan, For Sale?, THE MEMPHIS FLYER, http://www.memphisflyer.comlbackissues/

issue577/cvr577.htm (last visited Nov. 17, 2005) (reporting that Dliver owned Memphis's 8700 sq. ft.

Hunt-Phelan mansion from 1845 to 1851).

114. Patent Issued to Isaac Kirksey, Mardisville, cert. #388, Ser. #AL0960_.380 (Oct. 20, 1835)

(listing Isaac as assignee of Eli Moore Driver), available at the Bureau of Land Management's General

Land Office Records website, see supra note 105; Tract Book of the Mardisville Land Office, Township

17, Range 6 E., p. 112 (listing Isaac as patentee on land purchased by Driver).

115. Indenture, Reese Howell to Isaac Kirksey (Mar. 17, 1835), Talladega County Property Records,

bk. C, at 336-37 (recorded Nov. 18, 1842).

116. Indenture, Isaac Kirksey to Green T. McAfee, Talladega County Property Records, bk. D, at

596-98 (recorded Nov. 9, 1843).

117. Indenture, William J. Vann to Isaac Kirksey (June 24, 1839), Talladega County Property

Records, bk. C, at 305-07 (recorded Jan.. l3, 1840).

I..,

I

[Vol. 94:321

all deeds from this

res at the core of a

ega as a fairly large

nty.1I2 And he was

i thousands of acres

rI

i

I

I

,r to cultivate it. He

Len he first came to

Driver and Charles

:es from Driver to

ly and sell land. In

est of his Talladega

,cords indicate that

Ie sold unconnected

11843.

In exchange, Isaac

bank of the Chocolocho

llladega County Property

I

IT Hussady in a deed that

lladega County Property

130), http://alabamamapsThis map refers to the

rksey family genealogists

jrksey on DARRON, supra

farmland today, but the

\..SCAR Talladega Super

der.

Isaac paid $3.17 per acre

Mardisville Land Office,

i., at 109, 112 (recording

lYS that Isaac purchased);

) (same). Driver was very

5, at 165 (reporting that

'ouuty, Mississippi, in the

lphisflyer.com/backissuesl

d Memphis's 8700 sq. ft.

,0_.380 (Oct. 20, 1835)

d Management's General

[e Land Office, Township

~ounty

Property Records,

,pelt)' Records, bk. D, at

ladega County Property

I

I

I

I

2006]

THE STORY OF KIRKSEY V.

KIRKSEY

339

took a deed of trust on Lane's 440 acres, which lay about one-and-a-half to two

miles to the northeast of Locust Grove. lIS Lane defaulted on this loan in 1839,

and the trustees sold the land at auction in June of that year to Isaac. 1I9 Isaac

may not have been the first lienholder on the Lane property, however. A second

indenture dated June IS, 1840, reports that most of this same property was sold

at auction again in February 1840 to satisfy a separate judgment against

Lane. '2o Isaac purchased at this auction, too, though records show him buying

only the south half of the Lane property. Just how much of the Lane land Isaac

obtained is uncertain,121 but part of the Lane land is now known, as Old

_ Eastaboga, and Isaac is considered one of the village's founding fathers. l22 The

deed from this second auction was recorded in July 1840. '23

When Isaac sent his letter to Angelico in October, 1840, the Lane matter had

been settled a few months before, and Isaac had just gained additional land

separate from that which his slaves had been cultivating since 1834. Between

1835 and 1843, this is the only land that surviving records show Isaac obtained

in Talladega County separate from Locust Grove, which was itself still of

manageable size,l24 This is the land on which-or near which-Isaac placed

Angelico and her family. Locating the exact spot on which Angelico lived is

difficult, because Isaac sold the south half of the Lane propelty in February,

1841, just after Angelico arrived. '2s Surviving documents do not show conclusively that he owned the north half of the Lane property (he purchased it at the

sale in 1839, but not at the second sale in 1840), so exactly where Angelico

settled is something of a puzzle.

!l8. Id.

!l9. Id.

120. Indenture, Hugh P. Watson, Register and Master in Chancery, to Isaac Kirksey, Talladega

County Property Records, bk. C, at 396--97 (recorded July 13, 1840).

121. A chancery litigation report in the local paper, the Talladega Watchtower, on August 16, 1843,

recites that in February 1841 Isaac h~ld fee simple to a large portion of the Lane property that he

purchased in June of 1839, see supra note 119, but which we have no record of him purchasing again in

February of 1840 at the second auction, see supra note 120. Failure to record deeds of the time

probably accounts for this discrepancy.

122. DARRON, supra note 19, at 96-97 (citing an 1895 Dallas Morning News article about Isaac's

son). Isaac also reported in 1844 that he owned 560 acres in Benton County, where the northern half of

the Lane property was located. Tax Assessment Record for Benton County 1844, at 28 (on file at the

Anniston, Ala., Public Library).

123. Indenture, Hugh P. Watson, Register and Master in Chancery, to Isaac Kirksey, Talladega City

Property Records, bk. C, at 396-97 (recorded July 13, 1840).

124. The records we have searched contain several inconclusive leads that Isaac may well have

owned other property, but if so, it was purchased much earlier. For example, Calhoun County, Alabama,

Tract Book, at 100, repOlts eighty acres owned by Isaac several miles to the north in 1837, but Isaac

had no patent for tIus land (perhaps indicating he sold tile land before the patent issued), and a deed to it

is not in the surviving county records.

125. Notice, Isaac Kiksey [sic] v. Wm. Montgomery & Hugh Montgomery, TALLADEGA (Ala.)

WATCHTOWER, Aug. 16, 1843 (reporting Isaac's sale of the south half of tile Lane property to William

Montgomery on February 6, 1841). Montgomery failed to pay and sold the land to Hugh Montgomery.