+ 2 (,1 1/,1(

advertisement

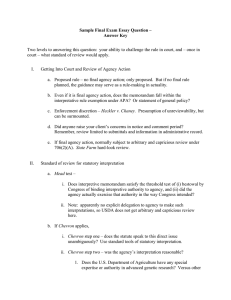

+(,121/,1( Citation: 2005-2006 Dev. Admin. L. & Reg. Prac. 57 2005-2006 Provided by: Texas Tech University Law School Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Mar 7 14:18:04 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1543-1991 Chapter 4 Judicial Review* This chapter examines highlights from federal caselaw developments governing judicial review of agency action from August 2005 to July 2006. It was a relatively quiet year on the judicial review front with no obvious doctrinal blockbuster such as the preceding year's National Cable & Telecommunications Ass'n v. Brand X Internet Services,' in which the Supreme Court fundamentally reworked the relationship between agency interpretive authority and judicial stare decisis. That said, the most important judicial review opinion of the last year was Gonzales v. Oregon,2 in which the Supreme Court narrowed the scope of Auer deference to agency regulatory interpretations and gave important guidance on the Mead problem of determining the scope of Chevron deference to agency statutory interpretations. In other opinions, the Court gave notable guidance on taxpayer standing,3 exhaustion,' retroactivity of jurisdiction-stripping statutes,' and construction of fee-shifting statutes.6 This chapter will examine these Supreme Court cases as well as a smattering of circuit court opinions on related topics. This chapter was written by Richard Murphy, Professor, William Mitchell College of Law (Committee Co-Chair) and Keith Rizzardi, Trial Attorney, U.S. Dept. of Justice, Wildlife and Marine Resources Section (Committee Vice-Chair). 1. 125 S. Ct. 2688 (2005) (holding that a Chevron-eligible agency statutory construction can trump an earlier judicial statutory construction). 2. 126 S. Ct. 904 (2006). 3. DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno, 126 S. Ct. 1854 (2006) (reviewing principles of standing generally and taxpayer standing more specifically). 4. Woodford v. Ngo, 126 S. Ct. 2378 (2006) (determining that, to properly "exhaust" remedies, a litigant must comply with "an agency's deadlines and other critical rules"). 5. Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, 126 S. Ct. 2749 (2006) (determining that "normal" rules of statutory construction apply to jurisdiction-stripping statutes). This case is also discussed herein in Constitutional Law and Separation of Powers (supra at 12-20) and Immigration and Naturalization (infra at 36566). 6. Arlington Cent. Dist. Bd. of Educ. v. Murphy, 126 S. Ct. 2455 (2006) (holding that a fee-shifting provision in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which authorizes the award of "reasonable attorneys' fees as part of the costs," does not authorize the award of expert fees). * 57 58 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice PART I. SCOPE OF REVIEW A. The Supreme Court Narrows Auer's "Domain" Auer (a/k/a Seminole Rock) deference instructs a court to defer to an agency's interpretation of its own ambiguous regulation so long as the interpretation is not clearly erroneous.' Scholars and courts have noted that Auer deference gives agencies an incentive to promulgate vague, "mushy" rules safe in the knowledge that they can always assign a definitive meaning to them later.' The Supreme Court took a step toward correcting this potential problem in Gonzales v. Oregon, holding that Auer deference does not apply to interpretations of regulations that merely "parrot" statutory text.9 The federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) regulates the use of drugs that fall on any of its five "schedules." 0 Unauthorized activities relating to these drugs (e.g., manufacture, distribution) are criminalized. Some of these drugs can be legally prescribed by registered physicians. To prevent unscrupulous physicians from issuing abusive prescriptions, the Attorney General in 1971 issued a regulation, 21 C.F.R. § 1306.04(a) (2005), that declares that prescriptions for controlled substances must "be issued for a legitimate medical purpose by an individual practitioner acting in the usual course of his professional practice." In 1994, Oregon voters adopted by ballot the Oregon Death With Dignity Act (ODWDA)," which allows physicians, subject to various restrictions, to prescribe lethal doses of drugs to terminally-ill patients. The drugs Oregon physicians have used for assisted suicide fall in Schedule II-a category of drugs that registered physicians can prescribe. The question then became whether the CSA's regime permits physicians to prescribe drugs to kill their patients. In November 2001, Attorney General 7. See Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452, 461-63 (1997). The doctrine is often said to have originated in Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand Co., 325 U.S. 410 (1945). 8. See, e.g., John F. Manning, ConstitutionalStructure and Judicial Deference to Agency Interpretationsof Agency Rules, 96 COLUM. L. REV. 612, 618 (1996) (suggesting on separation-of-powers grounds that courts apply Skidmore's weak form of deference rather than Auer's strong form to an agency's interpretation of its own rules). 9. 126 S. Ct. at 915-16. 10. Controlled Substances Act, 21 U.S.C. § 801 et seq. (1970). 11. Ore. Rev. Stat. § 127.800 et seq. (2003). Chapter4: JudicialReview 59 Ashcroft answered this question with a resounding "no"-issuing an interpretive rule declaring, among other things, that "assisting suicide is not a 'legitimate medical purpose' within the meaning of 21 C.F.R. § 1306.04, and that prescribing, dispensing, or administering federally controlled substances to assist suicide violates the Controlled Substances Act." 2 The State of Oregon and other plaintiffs sued to block enforcement of the interpretive rule-a result granted by both the district court and a divided panel of the Ninth Circuit.13 Before the Supreme Court, the government contended that the interpretive rule's treatment of the use of drugs for assisted suicide was a gloss on "prescription" as used by 21 CFR § 1306.04. As such, the interpretive rule was entitled to Auer's strong deference. Justice Kennedy, writing for a six-Justice majority, rejected this proposition. He explained that in Auer itself, "the underlying regulations gave specificity to a statutory scheme the Secretary was charged with enforcing and reflected the considerable experience and expertise the Department of Labor had acquired over time with respect to the complexities of the Fair Labor Standards Act."' 4 By contrast, 21 CFR § 1306.04 simply repeated or summarized phrases sprinkled through the CSA itself. Where such a "parroting" regulation adds nothing of semantic value to a statute, a so-called interpretation of that regulation boils down to nothing more than an interpretation of the statute itself. Thus, the Auer regime for deference to bona fide regulatory interpretations did not apply to the Ashcroft interpretive rule." Principles governing deference to statutory interpretations applied instead. B. MeadlChevron and Two Kinds of Delegation Problem 1. The Supreme Court Relates the Scope of an Agency's Rulemaking Power to the Scope of Its Chevron Power As explained in the preceding subsection, the Court in Gonzales determined that principles governing deference to agency statutory interpretations 12. 13. 14. 15. 66 Fed. Reg. 56,608 (Nov. 9, 2001). See Gonzales, 126 S. Ct. at 925. Id. at 915. Id. at 916 (explaining that "[an agency does not acquire special authority to interpret its own words when, instead of using its expertise and experi- ence to formulate a regulation, it has elected merely to paraphrase the statutory language"). Cf id. at 927-28 (Scalia, J., dissenting) (contending that it is "doubtful" that the anti-parroting exception to Auer deference exists, and that, in any event, the regulation at issue did not "parrot" the CSA). 60 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice applied to Attorney General Ashcroft's interpretive rule proscribing the prescription of controlled drugs for assisted suicide. As most readers of this chapter know too well, current doctrine on judicial deference to agency statutory interpretations is regrettably baroque. Under the Mead doctrine, a court should apply Chevron's strong deference to an agency's interpretation of a statute it administers if: (a) Congress has delegated power to the agency to imbue its interpretations with the "force of law"; and (b) the agency properly invoked this power.16 Although these conditions are easy enough to state in the abstract, they can be quite confusing to apply in practice, leading commentators to make alliterative references to the "Mead mess"" or the "Mead muddle."'" In any event, if either Mead condition goes unsatisfied, then a reviewing court should extend Skidmore's weak deference to the agency's interpretation-affirming it only if it is "persuasive" to the court.' 9 In Gonzales, the Court, applying Mead, concluded that Skidmore, not Chevron, applied to the Attorney General's interpretive handiwork. The Court could easily have justified this conclusion on the ground that the Attorney General had not properly invoked any delegated Chevron authority he might possess given that the interpretive rule had been issued with basically no notice or process at all-appearing as an unexpected bombshell in the Federal Register. Rather than take this easy road, the Court instead engaged in dense statutory analysis to explain that Congress had never delegated authority to the Attorney General in the first place to use his power to interpret the CSA to control the scope of state-approved medical practices. With regard to this delegation inquiry, Mead had advised that Congress can delegate Chevron-style interpretive authority expressly or implicitly. Congress can signal an implicit delegation of such authority to an agency "in a variety of ways, as by an agency's power to engage in adjudication or noticeand-comment rulemaking, or by some other indication of a comparable congressional intent."2 0 A core idea behind this list is that Congress would naturally expect courts to be especially deferential to those agency interpretations that have been subjected to extensive procedures designed to enhance public participation and agency deliberation. 16. United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218, 226-27 (2001). 17. William S. Jordan, III, Judicial Review of Informal Statutory Interpretations: The Answer is Chevron Step Two, Not Christensen or Mead, 54 ADMIN. L. REv. 719, 725 (2002) (decrying "Mead mess"). 18. Lisa Schultz Bressman, How Mead Has Muddled Judicial Review of Agency Action, 59 VAND. L. REV. 1443 (2005). 19. Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944). 20. 533 U.S. at 227. Chapter4: Judicial Review 61 In Gonzales, the Court refined the search for implicitly-delegated Chevron power by focusing carefully on the express scope of the Attorney General's rulemaking authority under the CSA. The Court first suggested that some express delegations of rulemaking authority are so broad as to grant an agency Chevron-type authority over pretty much any terms in the agency's statute. For instance, the Federal Communications Commission's express power under 47 U.S.C. § 201(b) to "prescribe such rules and regulations as may be necessary in the public interest to carry out the provisions" of the Communications Act apparently falls into this category. 21 The Court then observed that the Attorney General's express rulemaking powers under the CSA are not that broad. They include powers: ". . . to promulgate rules and regulations ... * relating to the registration and control of the manufacture, distribution, and dispensing of controlled substances and to listed chemicals," 22 and * to ". . . promulgate and enforce any rules, regulations, and procedures which he may deem necessary and appropriate for the efficient execution of hisfunctions under this subchapter." 23 At first glance, these rulemaking powers might seem quite broad indeed-particularly the power to promulgate rules for the "efficient execution" of the Attorney General's "functions." 24 The Court nonetheless stressed that "[a]s is evident from these sections, Congress did not delegate to the Attorney General authority to carry out or effect all provisions of the CSA."25 After extensive statutory analysis, the Court concluded that such rulemaking powers as the CSA did grant the Attorney General do not extend to "declaring illegitimate a medical standard for care and treatment of patients that is specifically authorized under state law."26 21. Gonzales v. Oregon, 126 S. Ct. 904, 916 (2006) (citing 47 U.S.C. § 201(b)). See also id. (noting that Chevron deference was owed Federal Reserve Board regulation as 15 U.S.C. § 1604(a) expressly delegated to the Board the power to issue regulations that in its judgment "are necessary or proper to effectuate the purposes of' the Board's statute). 22. 126 S. Ct. at 917 (quoting 21 U.S.C.A. § 821 (Supp.2005)). 23. Id. (quoting 21 U.S.C. § 871(b)) (emphasis added by this chapter). 24. Id. 25. Id. (emphasis added). 26. Id. at 916. 62 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice The practical upshot of this analysis: Canny construction of an agency's express rulemaking power is now a tool for limiting the implicit scope of the agency's Chevron-type interpretive power. 27 In addition to its exploration of the link between express and implicit delegations of power, two other aspects of the Mead/Chevron analysis in Gonzales bear noting. First, the Court observed that the CSA divides administrative authority between the Attorney General and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. The core rationale for the "presumption that Congress delegates interpretive lawmaking power to [an] agency rather than to the reviewing court" is the agency's "policymaking expertise."2 8 Here, the "expert" on "medical" judgments was the Secretary, a point that undermined the Attorney General's effort to use his interpretive authority to determine the scope of acceptable medical practices. Second, Gonzales marks the reappearance at the Supreme Court of the catchy elephants-in-mouseholes argument. The Court observed, "Congress ... does not alter the fundamental details of a regulatory scheme in vague terms or ancillary provisions-it does not, one might say, hide elephants in mouseholes."29 Put another way, where Congress intends to do something remarkable, it generally remarks upon it expressly-rather than requiring a surprising agency statutory interpretation to reveal it. Given the social importance of the assisted-suicide debate, had Congress wanted to delegate power to the Attorney General to use his interpretive authority to block state-sanctioned physician-assisted suicide, it would have done so in a more transparent way. 27. As has become customary in major cases treating the scope of Chevron, Justice Scalia brought his formidable administrative law powers to bear in a lengthy dissent (this time joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Thomas). Regarding the majority's analysis discussed above, he observed, "[t]he Court's exclusive focus on the explicit delegation provisions is, at best, a fossil of our pre-Chevron era; at least since Chevron, we have not conditioned our deferral to agency interpretations upon the existence of explicit delegation provisions." 126 S. Ct. at 936. 28. 126 S. Ct. at 921 (quoting Martin v. Occupational Safety and Health Review Comm'n, 499 U.S. 144, 153 (1991)). 29. Id. at 922 (quoting Whitman v. Am. Trucking Ass'ns, Inc., 531 U.S. 457, 468 (2001)). Chapter4: JudicialReview 63 2. An example of Chevron-Style "Delegation" Analysis from the D.C. Circuit The Supreme Court's Gonzales opinion bears an initial family resemblance to the D.C. Circuit's recent interesting opinion in American BarAss'n v. FTC.30 Both focus, in different fashions, on determining the scope of delegated power to an agency. In the former, the Supreme Court could not believe that Congress wanted the Attorney General to regulate the practice of medicine. In the latter, the D.C. Circuit could not believe that Congress wanted the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to regulate the practice of law. More specifically, the D.C. Circuit agreed with the American Bar Association that the FTC had overstepped its statutory authority by asserting that the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) subjected attorneys to the privacy constraints imposed on "financial institutions." The court began its analysis with the observation that the agency's use of the GLBA to regulate the practice of law amounted to an "attempted turf expansion" and violated the Supreme Court's maxim that Congress "does not . . . hide elephants in mouseholes."" (Prediction: This "elephants-inmouseholes" phrase is really going to catch on.) It concluded that, assuming Chevron applied at all, the agency had managed to lose at both step one and step two. At step one, the court held that it was clear enough that the GLBA, read in proper context, did not delegate authority to the FTC to regulate attorneys as "financial institutions." The court's explanation included the following discussion of the relation between statutory ambiguity and implicit congressional delegations of Chevron authority: We further recognize that the existence of ambiguity is not enough per se to warrant deference to the agency's interpretation. The ambiguity must be such as to make it appearthat Congress either explicitly or implicitly delegated authority to cure that ambiguity. . . . When we examine a scheme of the length, detail, and intricacy of the [statute] before us, we find it difficult to believe that Congress, by any remaining ambiguity, intended [for the FTC] to undertake the regulation of the profession of law. . . . To find this interpreta- 30. 430 F.3d 457 (D.C. Cir. 2005). 31. Id. at 467 (quoting Whitman v. Am. Trucking Ass'ns, Inc., 531 U.S. 457, 468 (2001)). 64 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice tion deference-worthy, we would have to conclude that Congress not only had hidden a rather large elephant in a rather obscure mousehole, but had buried the ambiguity in which the pachyderm lurks beneath an incredibly deep mound of specificity, none of which bears the footprints of the beast or any indication that Congress even suspected its presence.32 Given its discussion of "delegation" as a prerequisite to Chevron deference, the preceding passage might look to a quick glance like a Mead analysis, but it is not. A Mead-style inquiry checks whether factors other than statutory ambiguity itself justify the conclusion that Congress has delegated Chevron-powerto an agency to resolve statutory ambiguities. Thus, in Gonzales, as we have just seen, the Court focused on the significance of the Attorney General's express rulemaking power to determine the scope of his Chevron authority to control interpretation of the CSA. In American Bar Ass'n, the court's analysis focused on a very different kind of "delegation" questionwhether the agency's organic statute itself could plausibly be read to grant the agency the power it claimed. Thus, the D.C. Circuit was not engaged in a Mead analysis at all; instead, it simply was applying the basic Chevron twostep to determine the scope of the FTC's "jurisdiction" pursuant to the GLBA. 33 To avoid making Chevron/Mead any more confusing than it already is, it would seem best to keep these two different kinds of "delegation" issues carefully confined to their own doctrinal boxes. 34 32. Id. at 469 (emphasis added) (citations omitted). 33. The question of whether Chevron applies to interpretations of the scope of an agency's "jurisdiction" is somewhat unsettled. See e.g., EEOC v. Seafarers Int'l Union, 394 F.3d 197, 201 (4th Cir. 2005) (holding that Chevron applies to terms that limit agency jurisdiction); Bullcreek v. Nuclear Regulatory Comm'n, 359 F.3d 536, 540-41 (D.C. Cir. 2004) ("The court typically defers under Chevron ... to an agency's interpretation of its own jurisdiction under a statute that it implements."). But see N. Ill. Steel Supply Co. v. Sec'y of Labor, 294 F.3d 844, 846-47 (7th Cir. 2002) (observing that MHSA had jurisdiction over "operators" of mines; applying de novo review to agency's interpretation of that term). 34. Cf Lisa Bressman, Judicial Review in DEVELOPMENTS INADMINISTRATIVE LAW AND REGULATORY PRACTICE 2004-05, 98-99 (Jeffrey S. Lubbers ed., 2006) (noting confusion in case law concerning the relation of "jurisdictional" to "delegation" questions in Mead/Chevron analysis). Chapter 4: JudicialReview 65 C. Might Chevron Apply to Agency Interpretations of Judicial Precedents? The most important environmental law opinion of the last Supreme Court term was Rapanos v. United States,3 5 in which the Court examined the meaning of the phrase "waters of the United States" as used by the Clean Water Act (CWA).36 The scope of this statutory phrase is critical to determining the power of the Corps of Engineers to regulate the use of relatively isolated bodies of water (or really damp ground). Regulations issued by the Corps had interpreted this phrase to cover: traditional navigable waters, their tributaries, and adjacent wetlands.37 The Court was unable to form a majority with regard to whether the Corps' approach was permissible under Chevron. A four-Justice plurality, led by Justice Scalia, held that: (a) the "only plausible interpretation" of "waters of the United States" includes "only ... relatively permanent, standing, or continuously flowing bodies of water"38 ; and (b) to be "adjacent" to covered "waters" (and thus also covered by the Act), a wetland must have "a continuous surface connection to bodies that are 'waters of the United States' in their own right."" On the plurality's view, the CWA's jurisdiction does not extend 40 to "channels through which water flows intermittently or ephemerally." Justice Stevens led a four-Justice dissent that upheld as reasonable the Corps' view that the "waters of the United States" need not be "permanent" and that wetlands can be "adjacent" without having a "continuous surface connection" with other "waters." 4 1 Justice Kennedy, writing only for himself, held the balance of power. Relying heavily on Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. Army Corps of Engineers (SWANCC), 42 he concluded that: (a) "waters" need not be permanent; but also (b) to assert jurisdiction over a "wetland," the Corps has 35. 126 S. Ct. 2208 (2006). This case is also discussed herein in Constitutional Law and Separation of Powers (supra at 39) and Environmental and Natural Resources Regulation (infra at 266-70). 36. 33 U.S.C. § 1362(7). 37. 126 S. Ct. at 2216 (citing various provisions of 33 CFR § 328.3(a) (2004)) (Scalia, J., plurality). 38. Id. at 2225. 39. Id. at 2226. 40. Id. at 2225. 41. Id. at 2259-62 (Stevens, J., dissenting). 42. 531 U.S. 159 (2001). 66 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice to demonstrate that the wetland has a "significant nexus" to "navigable waters."43 (Have you kept score? There will not be a quiz.) Rapanos marks an important application of Chevron principles, and a careful reader of its dense opinions can find illustrative invocations of interpretive tools such as dictionaries,' canons of construction,4 5 and the significance of congressional acquiescence.4 6 Rapanos does not, however, break significant new ground in terms of generally applicable administrative-law principles except perhaps in one notable, potential respect. Justice Breyer wrote a brief dissent in which he observed that, to his mind, the Court's earlier SWANCC opinion and Justice Kennedy's concurrence in Rapanos had incorrectly "written a 'nexus' requirement" into the CWA's definition of "waters of the United States."47 Justice Breyer added that the Corps "may write regulations defining the term-something it has not yet done. And the courts must give those regulations appropriate [i.e. Chevron] deference."48 He thus seems to suggest that courts should defer to reasonable agency interpretations of at least some judicial statutory constructions. 43. Rapanos, 126 S. Ct. at 2242, 2248 (Kennedy, J., concurring). 44. Id. at 2221 (Scalia, J., plurality) (quoting Webster's New Int'l Dictionary (2d ed. 1954) for definition of "waters"; describing Justice Kennedy's use of that definition as "strange"); id. at 2242 (Kennedy, J., concurring) (debating plurality's interpretation of dictionary definition of "waters"); id. at 2260 (Stevens, J., dissenting) (observing that "the plurality cites a dictionary for a proposition it does not contain"; quoting a later edition of Webster's for support). 45. Id. at 2224 (Scalia, J., plurality) (declining to construe CWA in a way that would permit "unprecedented intrusion into traditional state authority" and would "authorize an agency theory of jurisdiction that presses the envelope of constitutional validity"); id. at 2246 (Kennedy, J., concurring) (criticizing plurality's use of constitutional avoidance canon); id. at 2261 (Stevens, J., dissenting) (criticizing plurality's use of canons). 46. Id. at 2231 (Scalia, J., plurality) (criticizing dissent's reliance on congressional acquiescence to Corps' statutory interpretation); id. at 2258 (Stevens, J., dissenting) (claiming that Corps' interpretation "is further confirmed by Congress' deliberate acquiescence in the Corps' regulations in 1977"). 47. Id. at 2266 (Breyer, J., dissenting). 48. Id. On a related note, recall that in National Cable & Telecommunications Ass'n v. Brand X Internet Services, 125 S. Ct. 2688 (2005), the Court held that an agency's reasonable, Chevron-eligible statutory construction can trump an earlier judicial gloss on the same statutory language. Chapter 4: Judicial Review 67 PART II. ACCESS TO THE COURTS A. On (Non) Retroactivity Analysis of Jurisdiction-Stripping Statutes In its monumentally important opinion Hamdan v. Rumsfeld,4 9 the Supreme Court held that military commissions established by the executive branch to try suspected terrorists in the war-on-terror were illegal as they violated both the Uniform Code of Military Justice and applicable portions of the Geneva Conventions."o To get to these merits issues, however, the Court first had to assess the jurisdiction-stripping effects of the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 (DTA), which was enacted while Hamdan's case was pending. The DTA provides that "no court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider an application for a writ of habeas corpus filed by or on behalf of an alien detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba."' The majority, led by Justice Stevens, held that this provision did not strip the Supreme Court of its jurisdiction over Hamdan's case; Justice Scalia, dissenting, contended that it did. The two opinions of course jousted regarding how to construe the text of the specific statutory provisions at issue. More fundamentally, however, they also disagreed over whether a rule of law exists that requires application of jurisdiction-stripping statutes to pending cases absent express instructions to the contrary. The majority insisted that "normal rules of construction" apply to jurisdiction-stripping statutes and that a "contextual reading" of the statutory language at issue indicated that the DTA did not apply to habeas cases pending at the time of enactment-such as Hamdan's.52 Applying "normal" interpretive rules, the Court noted in particular that Congress had expressly provided that other provisions of the DTA did apply to pending cases. As the majority saw it, Congress's failure to include similarly express instructions regarding the DTA's limits on habeas jurisdiction suggested the "negative inference" that these limits did not apply to pending cases-an expressio unius point buttressed by the majority's reading of the DTA's legislative history. 49. 126 S. Ct. 2749 (2006). 50. See id. at 2759. 51. Detainee Treatment Act of 2005, H.R. 2863, 109th Cong. § 1005(e)(1) (2005). 52. See Hamdan, 126 S. Ct. at 2764-65. For Justice Scalia's take on these points-and his lambasting of the majority's use of legislative history in particular, see id. at 2812-17 (Scalia, J., dissenting). 53. See id. at 2765-66. 68 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice For the record, Justice Scalia countered that the majority had junked "[a]n ancient and unbroken line of authority attest[ing] that statutes ousting jurisdiction unambiguously apply to cases pending at their effective date."- B. Standing-Two Notable Discussions of Taxpayer Standing 1. The Supreme Court Explains State Taxpayer Standing Those looking for a review of taxpayer-standing principles-and really, who isn't?-might start with the Supreme Court's opinion in DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno,5 in which the Court ruled that state taxpayers lacked standing to challenge a state franchise-tax credit on Commerce Clause grounds. The plaintiffs based their claim to standing in part on the notion that, by giving DaimlerChrysler a tax break, the state had depleted its revenues and burdened its taxpayers. The Court rejected this argument, observing that the state taxpayers' claimed injuries were not "'concrete and particularized"' but instead generalized and "'indefinite.'" 5 6 Moreover, rather than being "'actual or imminent,"' the plaintiffs' injury was "'conjectural or hypothetical' in that: (a) the tax break might increasetax revenues due to its effect on economic activity; and (b) even if the tax break caused revenues to decrease, the plaintiffs would not suffer injury unless the state increased taxes on them to make up the deficit-a totally speculative proposition." The plaintiffs had tried to avail themselves of the Court's uniquely favorable treatment of taxpayer standing in Flast v. Cohen, which held that "'a taxpayer will have standing consistent with Article III to invoke federal judicial power when he alleges that congressional action under the taxing and spending clause is in derogation"' of the Establishment Clause." The plaintiffs seized on Flast's broad hint that federal taxpayers might also have standing to contest violations of other constitutional constraints on congressional power (e.g., the Commerce Clause), but, as the Court noted, the plaintiffs had "candidly" conceded that "only the Establishment Clause has supported 59 federal taxpayer suits since Flast." 54. Id. at 2810 (Scalia, J., dissenting). 55. 126 S. Ct 1854 (2006). 56. See id. at 1862 (quoting Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555,560 (1992) and Massachusetts v. Mellon, 262 U.S. 447, 488 (1923)). 57. See id (quoting Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555,560 (1992)). 58. Id. at 1864 (quoting Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83, 105-06 (1968)). 59. Id. (quotation marks omitted). Chapter4: Judicial Review 69 The Supreme Court resisted the plaintiffs' entreaties to broaden application of Flast's narrow rule. The plaintiffs' theory of injury for its Commerce Clause claim required speculation concerning the state's reaction to a (conjectured) loss of tax revenue-i.e., the loss would cause the state to burden the plaintiffs with more taxes. By contrast, under Flast, such speculation was unnecessary because the very act of extracting taxes to pay for an Establishment Clause violation causes cognizable "injury."w In addition, were the Court to accept that state taxpayers have standing under Flastto contest Commerce Clause violations, then there would be "no principled way of distinguishing those other constitutional provisions that we have recognized constrain governments' taxing and spending decisions."61 Thus, allowing this particular camel's nose into the tent would make a hash of standing law by transforming "federal courts into forums for taxpayers' 'generalized grievances."' 62 The plaintiffs also tried a supplemental jurisdiction gambit that went nowhere. They contended that: (a) the city of Toledo had violated the Commerce Clause by granting property-tax waivers to DaimlerChrysler; (b) they had standing as "municipal" taxpayers to make this property-tax claim; and therefore (c) the federal courts could hear their state-taxpayer, franchise-taxcredit claim under the supplemental jurisdiction principles of United Mine Workers v. Gibbs.63 As the Court described their stance, the plaintiffs had assumed that Gibbs stood for the proposition "that federal jurisdiction extends to all claims sufficiently related to a claim within Article III to be part of the same case, regardless of the nature of the deficiency that would keep the former claims out of federal court if presented on their own."' The Court corrected this assumption, observing: (a) that it has read the Gibbs gloss on supplemental jurisdiction narrowly in the past; and (b) that each claim in a federal case must "satisfy those elements of the Article III inquiry, such as constitutional standing, that serve to identify those disputes which are appropriately resolved through the judicial process."6 In short, although the Gibbs gloss on the concept of the Article III "case" allows a federal court to hear certain state-law claims that do not satisfy diversity requirements, it is not a blank check for allowing claims to get around basic requirements relating to injury-in-fact, ripeness, mootness, etc.6 60. See id. at 1865. 61. Id. 62. Id. (quoting Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83, 106 (1968)). 63. 383 U.S. 715 (1966). 64. Cuno, 126 S. Ct at 1865. 65. Id. at 1867 (citation and quotation marks omitted). 66. See id. at 1867. 70 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice The best part of Cuno for anyone who has ever found constitutionalstanding doctrine confusing has got to be Justice Ginsburg's brief concurrence, in which she seems to suggest dumping 25 years' worth of major precedents on the subject. 67 2. The Seventh Circuit Debates Taxpayer-Standing and Extends Flast In Freedom from Religion Foundation,Inc. v. Chao,68 a Seventh Circuit panel split with regard to whether taxpayers had standing to challenge the funding of conferences held by executive-branch agencies to promote "FaithBased and Community Initiatives." Had Congress invoked its spending power to fund this program directly, it seems plain enough that the plaintiffs would have enjoyed standing to challenge it under the narrow rule of Flast just discussed in the preceding subsection. The program, however, was created by President Bush via executive order, and the money for it apparently came from discretionary allocations by agencies of appropriations for general administrative expenses. For Judge Posner in the majority, this was a distinction without a salient difference. Hammering this point home, he observed that standing would certainly exist under Flast were, for example, the Secretary of Homeland Security to use unearmarked funds to build a mosque and pay the salary of its imam to reduce the likelihood of Islamic terrorism.6 9 Judge Ripple, dissenting, took the view that the majority's application of Flast to executive action undirected by Congress amounted to a "dramatic expansion of current standing doctrine" that "cut[ ] the concept of taxpayer standing loose from its moorings." 0 Even if, by some small chance, you are not consumed by the narrow problem of the scope of taxpayer-standing to challenge Establishment Clause violations, Freedom from Religion is an opinion well worth reading for its concise explanation of how the law of constitutional standing managed to 67. See id. at 1869 (declining to endorse limits on standing declared in Simon v. Eastern Ky. Welfare Rights Org., 426 U.S. 26 (1976), Valley Forge Christian Coll. v. Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Inc., 454 U.S. 464 (1982), Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984), and Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992)). 68. 433 F.3d 989 (7th Cir. 2006). 69. See id .at 994. 70. Id. at 997, 998 (Ripple, J., dissenting). Chapter4: JudicialReview 71 evolve into its current state and for the debate between its majority and dissenting opinions. Certainly, any review of standing case-law that includes the observation, "[n]otions of standing have changed in ways to induce apoplexy in an eighteenth-century lawyer,"7' must have some promise, no? C. Administrative Exhaustion Means Proper Exhaustion In Woodford v. Ngo,72 the majority and dissenting opinions debated whether "exhaustion"-as administrative law generally uses that term-requires "proper exhaustion" or "exhaustion simpliciter." The six-Justice majority, in an opinion authored by Justice Alito, insisted on "proper exhaustion," which requires a litigant to make use of available administrative remedies and, along the way, to comply with "an agency's deadlines and other critical procedural rules."73 By contrast, Justice Stevens' dissenting opinion contended that the concept of "exhaustion"-by itself-merely requires that administrative remedies no longer be available to a litigant.74 The occasion for this debate was the need to interpret the force of a provision from the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) that provides: No action shall be brought with respect to prison conditions under section 1983 of this title, or any other Federal law, by a prisoner confined in any jail, prison, or other correctional facility until such administrativeremedies as are available are exhausted." If "exhaustion" must be achieved "properly," then a prisoner cannot exhaust by filing procedurally-defective administrative grievances or appeals. If, by contrast, "exhaustion" has no "propriety" requirement, then it would seem that prisoners might achieve it by, for instance, simply waiting for administrative deadlines to pass. Starting with the dissent first, Justice Stevens' key move was to contend that the administrative law concept of "exhaustion" does not by itself entail the enforcement mechanism of "procedural default" or "waiver."76 Rather, 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. Id. at 990. 126 S. Ct. 2378 (2006). Id. at 2385-86. See id. at 2396-97 (Stevens, J., dissenting). Id. at 2378 (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 1997e(a)) (emphasis added by Court). Id. at 2396-97 (Stevens, J., dissenting). 72 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice this penalty is imposed by either Congress or the courts as a separate analytical move in some but not all contexts where exhaustion is required.7 Where Congress imposes a waiver penalty, it says so clearly-e.g., it instructs courts to refuse to consider arguments that a litigant did not raise before the agency." Judges impose this penalty as "'an analogy to the rule that appellate courts will not consider arguments not raised before the trial courts.'" 7 9 Applying these principles to the PLRA: (a) it contains no express instructions from Congress on waiver; and (b) a prisoner's section 1983 claim does not seek "direct review of an order entered in [a] grievance procedure" but instead presses an original action in district court.s0 Therefore, as Justice Stevens saw the matter, Congress did not and the courts should not read a waiver penalty into the PLRA. By contrast, the majority read the Court's precedents-at least outside the distinctive context of habeas review-to signify that the term "exhaustion" entails its own enforcement regime-i.e., if you do not follow an agency's "critical procedural rules" governing its internal remedies, then you cannot satisfy the exhaustion prerequisite for judicial review." Thus, simply by using the term "exhaustion" in the PLRA, Congress had imposed a waiver penalty on those who do not exhaust "properly." Reading the PLRA to require "proper exhaustion" raises the specter that prison officials might trip up unwary prisoners with unfair procedural requirements. Judge-made doctrine has dealt with this problem by conceding that the exhaustion requirement has exceptions (e.g., where seeking administrative review would be "futile"). The Court was careful to bracket this issue for another day, observing that "we have no occasion here to decide" how to address efforts by officials to "trip[ J up all but the most skillful prisoners."" 77. See id. at 2398 (Stevens, J., dissenting). 78. See id. (Stevens, J., dissenting) (noting, for example, that the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. § 160(e), forbids consideration of claims "that ha[ve] not been urged" before the administrative agency). 79. Id. (quoting Sims v. Apfel, 530 U.S. 103, 108-09 (2000)) (Stevens, J., dissenting). 80. Id. at 2399 (Stevens, J., dissenting). 81. See id. at 2385-86. 82. Id. at 2392-93. Chapter4: JudicialReview 73 PART I. ATTORNEYS' FEES AND COSTS A. "Reasonable Attorneys' Fees" Don't Include Experts (No Matter What the Conference Committee May Have Thought) In Arlington Central School District Board of Education v. Murphy, the Court determined that a fee-shifting provision in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which authorizes awards of "reasonable attorneys' fees as part of the costs," does not authorize awards of expert fees." The Court's road to this conclusion has broad implications for the construction of statutes that implement Congress's Spending Clause power and also contains an illuminating dispute over the use of legislative history. The five-Justice majority observed: (a) Congress had enacted IDEA pursuant to its Spending Clause power; and (b) where Congress wishes to attach conditions to a State's acceptance of federal funds, it must state those conditions "unambiguously" under the doctrine of Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Halderman.8 4 In the majority's view, IDEA's fee-shifting provision did "not even hint that acceptance of IDEA funds makes a State responsible for reimbursing prevailing parents for services rendered by experts."" Construing this provision to authorize the award of expert fees therefore plainly flunked the "clear notice" test. The majority buttressed this conclusion by noting that the Court's own precedents had taken a narrow approach to construing similar fee-shifting provisions in the past.8 6 Perhaps the largest fly in the majority's analytical ointment was that its construction directly contradicted the IDEA's Conference Committee Report, which expressly instructed that "the term 'attorneys' fees as part of the costs' include[s] reasonable expenses and fees of expert witnesses . . . ."I The majority addressed this point by reiterating that, in light of the statutory text and the weight of precedent, there was no way that this legislative history, by itself, could provide states with Pennhurst's"clear notice." 8 83. 126 S. Ct. 2455 (2006) (construing 20 U.S.C. § 1415(i)(3)(B)). 84. See id. at 2459 (citing Pennhurst State Sch. and Hosp. v. Halderman, 451 U.S. 1, 17 (1981)). 85. Id. 86. See id. at 2461-62 (citing Crawford Fitting Co. v. J. T. Gibbons, Inc., 482 U.S. 437 (1987) (interpreting "costs" as used by FED. R. Civ. P.. 54(d)); W. Va. Univ. Hosps., Inc. v. Casey, 499 U.S. 83 (1991) (interpreting fee-shifting provision of 42 U.S.C. § 1988)). 87. Id. at 2462 (discussing import of H. R. Conf. Rep. No. 99-687, at 5 (1986)). 88. See id. 74 Developments in Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice Four Justices rejected the premise that Pennhurt's "clear notice" requirement applied to such fine statutory details as the precise contours of IDEA's fee-shifting provision." Three dissenting Justices would have followed the legislative history to the conclusion that IDEA's fee-shifting provision covers expert fees. 0 B. But "Reasonable Attorneys' Fees and Costs" Might Include the Janitor's Bill A debate over what types of costs should be included as "reasonable attorney's fees and costs" emerged in the Ninth Circuit as well. In Trustees of the Construction Industry & Laborers Health & Welfare Trust v. Redland Insurance Co.,9' the Trustees prevailed in an action to collect delinquent benefit contributions owed to trusts established under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). The Trustees then sought an award of "reasonable attorney's fees and costs of the action" under ERISA pursuant to 29 U.S.C. § 1132(g)(2)(D). The Ninth Circuit held that the district court erred in denying costs for work performed by non-attorneys such as law clerks and paralegals, because a "reasonable attorney's fee ... must take into account the work not only of attorneys, but also of secretaries, messengers, librarians, janitors, and others whose labor contributes to work product for which an attorney bills her client."92 In this same vein, after acknowledging that a circuit split existed on the issue, the court held that reasonable charges for computerized research may be recovered as "attorney's fees" under § 1132(g)(2)(D) if separate billing for such expenses is "the prevailing practice in the local community."93 89. See id. at 2471 (Breyer, J., dissenting) (contending that "Pennhurst's clearstatement requirement does not demand textual clarity in respect to every detail"); see also id. at 2464 (Ginsburg, J., concurring in part and in judgment) (concluding that majority's application of Pennhurst's "clear notice" rule was "unwarranted"). 90. See id. at 2466-68 (Breyer, J., dissenting) (offering detailed analysis of legislative history of IDEA's fee-shifting provision). 91. 460 F.3d 1253 (9th Cir. 2006). 92. Id. at 1256-57 (quoting Missouri v. Jenkins, 491 U.S. 274, 285 (1989)). 93. Id. at 1258-59 (citing, inter alia, Arbor Hill Concerned Citizens Neighborhood Ass'n v. County of Albany, 369 F.3d 91, 98 (2d Cir. 2004) ("If [the firm] normally bills its paying clients for the cost of online research services, that expense should be included in the fee award."); Standley v. Chilhowee R-IV Chapter4: JudicialReview 75 The court was careful to add, however, that "'reasonable attorney's fees' do not include costs that, like expert fees, have by tradition and statute been treated as a category of expenses distinct from attorney's fees." 94 Sch. Dist., 5 F.3d 319, 325 (8th Cir. 1993) ("computer-based legal research must be factored into the attorneys' hourly rate, hence the cost of the computer time may not be added to the fee award"). 94. Id. (citing W. Va. Univ. Hosps., Inc. v. Casey, 499 U.S. 83, 99-100 (1991)).