The Scope o.t· Federal Regulation ... 1uclear Waste Brian E. Murray

advertisement

The Scope o.t· Federal Regulation o.t· the 'l'ransportation of

1uclear

Waste

Brian E. Murray

1s t

s .s . '

1 981

Radiation is like oppression,

the average daily kina of subliminal toothache you get almost used to, the stench or

chlorine in the water, o.t· smog in the wind

- tvlarge Piercy

Very few laymen (which would probably include almost all

of us) understand just exactly what radioactive wastes (redwastes) and raaiation are. Since the purpose of this paper is

to discuss the scope and extent of the federal regulatory scheme

in the area of the transportation of these radwastes, it woula

perhaps be helpful at the outset to generally discuss what these

radwastes are, their inherent dangers, and their classifications.

There are two different "levels" of radwaste. First is that

category referred to as "low-level" radioactive waste. Low-level

waste is but one phase ot· the nuclear t·uel cycle that presents

hazards to human and environmental safety. A typical 10Uu-megawatt nuclear power plant produces about 2UUU to 4UUU cubic feet

per year of low-level waste 1 , which incluaes such articles as

contaminated glassware, containers, clothing, gloves, tools,

filters, rags, paper, etc ••• ~. These wastes are usually placea

in drums which are then fillea with concrete and disposed or.

At one time, the preferred method o! aisposal was to dump these

arums into the ocean, but recent EPA tests have shown that over

periods ot· time these drums deteriorate on the ocean f'loor,

thereby contaminating the aquatic environment. Currently,

shallow lana burial is the primary method

o~

disposal of these

wastes 2 •

The second "level" of radwaste is referred to as "highlevel" waste. This category accounts t·or only a small percent

of the entire amount of wastes generated, but represents about

90% of the radioactivity associated with the nuclear 1'uel cycle~.

'1'here are three sources o! high-level raawastes: !iss ion

proaucts, activation proaucts, and transuranic elements.

products are createa by the fissioning of

on3~a

uranium-~5~

~ission

atoms;

activation proaucts are produced when impurities ana ruel clanding material are exposed to neutrons in the nuclear reactor;

and transuranic elements appear when uranium-238 in the fuel

absorbs neutrons.

There is a common misconception that radwaste produced by

the military far exceeds that produced by private ventures.

While the military does produce large quantities, in terms of

pure toxic! ty (i.e. radioactivity), t~.~!pri vate nuclear industry overtook the defense program in 1977. And the private sector

produces waste at a much raster rate than does the defense inaustry 4 •

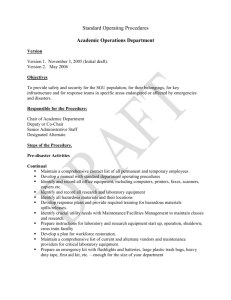

There are four major federal agencies concerned with the nuclear waste management process. These are the Department of

Energy (DOE), the Department of Transportation (DOT), the

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), and the Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA). Since this paper is focused primarily on those regulations arfecting the transportation of

nuclear wastes, we will discuss mainly the roles or the DOT

and the EPA.

The DOT regulates the shipment of raaioactive materials, and

under an agreement wi.th the NRC, the DOT is responsible for promulga[ting and en1·orcing sa1·ety standards for Type A pa ckaging and shipping containers, and ror the labelling and classification of all packages 6 • The DOT also implements sarety standards for the mechanical condition of carrier equipment and sets

specifications for carrier personnel 7 •

The transportation phase of the nuclear fuel cycle includes

the shipment of spent fuel or radwaste to treatment to treatment, storage, or disposal facilities. Under the throwaway cycle,

- 2 -oo3~n

spent fuEl would be shippea to a storage facility and then to

a permanent disposal site. Casks for shipping spent fuel usually

hold 5.2 tons of spent fuel and weigh around 10U tons.

Such a cask may contain up to 20 million curies of radioactivity, including 50,000 curies of gaseous fission proaucts.

These

cyl~narical

casks are 5 feet in diameter ana 15 to 18

feet long. They are constructed with thick steel walls, and

filled with dense sheathing material (e.g. lead), ana are

equipped with coolant or heat dissipating equipment8 • Because

of their size ana weight, spent .t"uel shipping casks are usually shipped by rail, although smaller casks can be shipped by

truck.

The transportation scheme is more complex with the recycling

alternative. First, spent ruel would be shipped to a reprocessing plant, and then the reprocessing waste woula be shipped

by truck or rail to storage or disposal !·acili ties. These wastes

would be enclosed in thick stainless steel canisters, 1U feet

long with an inside diameter or 1 root. A single canister would

hold the solidified waste from the reprocessing or about 5.2

metric tons of spent fuel 9 . Thus, a year's waste from a 1UUUmegawatt nuclear reactor could be contained in 10 canisters.

These reprocessing waste canisters would then be shipped to storage or disposal sites in casks similar to those used to transport spent ruel. Obviously, the rupture of one of these canisters would cause less harm than the rupture o!· a spent t·uel

cask as the waste contained in the canister is solidi!ied, ana

thus no gases would be released upon rupture.

rt· spent fuel is recycled, plutonium would be extracted as

part of the reprocessing operation and would be shipped separately in solid oxide t·orm to _AuelJ:abrication plants by truck

-5-UO~i~lu

or rail. Since plutonium does not emit penetrating radiation,

its containers do not require heavy shielaing although care

must be taken to prevent criticality 10 • Nevertheless, the shipment ot plutonium involves the hazard

o~

exposure to radiation

from the accidental rupture of the waste container and the danger of attented hijacking by criminal or terrorist groups.

The principal goal of nuclear waste management must be to

ensure that radwaste is completely isolated from the environment during its hazardous lifetime. To achieve this goal, the

avoidance and equitable distribution of risks is the most crucial specific problem to confront in formulating a waste management program. Risk avoiaance in the transportation area of raawaste management involves a number of choices, among which are

modes of transportation, and packaging standards. Land transportation is generally safer than shipment by air or sea, because the consequences of an accident are less severe. Not

only are radwaste containers less likely to rupture during

land transportation, but it stands to reason that cleanup operations are easier and more effective

on:~

land than in the at-

mosphere or in large bodies of water.

In general, it seems desirable to limit (or minimize) the

number of trips. Thus railroads offer the greatest advantage

among the various forms of land transportation because they

are able to carry larger quantities of radwaste in a single

trip.

Packaging is another means by which

transportation risks

can be reduced. Regardless of the number of precautions taken,

some accidents will occur in transit. Since railroads have a

derailment rate of 10- 6 per car mile, 2 derailments per year

should be expected if 1UUO casks of radwaste are shipped by

1\a~l) . •

\1U't

--

Lf

rail fpr a distance of 2000 miles annually 11 • Since derailments are statistically certain, packaging standards must be

high enough to prevent such accidents f'rom becoming disasters.

NRC regulations currently proviae that dhipping casks must be

designed to withstand a 3U m.p.h. "free drop" crash onto a solid ana unyielding surf'ace, exposure to a thermal test !or 5U

minutes, and submersion in water f'or 8 hours 12 •

Further improvements are possible 13. A sauna waste management policy must not only require strict compliance with existing standards, but should also encourage research and development in the areas regulatea.

The Transportation Sa:t"ety Act of' 1Y74, or the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act (HMTA), was enacteu by Congress to

improve the regulatory and enforcement authority of the Secretary of Transportation to protect the nation aaequately against the risks; to life and property which are inherent in the

transportation of hazardous materials in commerce 14 • The Secretary may designate any quantity or form or material which

may pose an unreasonable risk to health ana safety or property

when transported in commerce as a hazaraous material. Transportation means movement by any moae of transport 15 •

The HMTA also establishes criteria !'or

;~he

handling and

transport or hazardous materials. These criteria incluae the

minimum nimber ot· personnel, the minimum level o1· training and

qualifications of personnel, the type and frequency or inspections,and procedures and equipment ror such activities as

detection ot· risks, hBndling o1· materials, and monitoring

sarety assurance measures 1b •

The DOT has issued extensive regulations to enforee the

provisions or the

HM~A.

Congress considered the HMTA in the

enactment or the RCRA 17 , and directed the Administrator to

coordinate the regulations promulgated unaer the

those promulgated under the HMTA 18 •

~he

R~hA

with

regulations or the DUT which pertain to the trans-

portation ot· hazardous materials fall under Subtitle B of

Title 49 of the CFR. This subtitle is extremely extensive and

contains over 1200 pages of text. We will restrict our inquiry

to Parts 100-17Y of Tltle 49, as these have the greatest relevance to generators and transporters of nuclear waste.

General information relating to the transportation of hazardous waste, including hazardous materials incidents, can be

found in Part 171 or the Hazardous Materials Transportation Regulations (HMTR) 19 •

Part 172 includes the Hazardous Materials Table (HMT), an

important element for compliance with the regulations, and was

amended in the May 22, 1980 regulations to include hazardous

wastes 20 • Part 173 21 provides the requirements for preparation

of hazardous materials for shipment. It designates the stanaards for packaging, quantity limitations, and the use andreuse of shipping containers. Packaging requirements for hazardous materials have been compiled into three categories:

1. Subpart A- general requirements for shipments and packaging

2. Subpart B - requirements for preparation of hazardous

materials for transport, and

3. Subparts C through N - requirements t·or specific hazar-

dous materials.

A key component of the packaging requirements in Subpart A or

173 is section 173.2. This section classifies those hazardous materials which have more than one hazard, due to their

properties, into a hierarchy of hazards

Parts 174 through 176 of the HMT.R outline the various operating, handling, and loading requirements for the wastes that

are shipped by rail, air, and vesse1 2 !~

Part 177 governs the transportation of hazardous materials

by public highway, and is in all probability the most widely

used part or the regulations. This part, among other things,

sets stanaards by which the materials may be carried on motor

vehicles which transport passengers for hire (an indication of

the extensive treatment given hazardous materials by the VOT),

and the requirements for motor vehicle operators involved in

an accident while transporting such materials.

Parts 178 and 179 contain aetailed requirements as to the

specifications for shipping containers and tank cars. These

include standards ror the quality of materials usea in construction, and the methods of construction, sealing, ana testing22.

The

HM~R

and RCRA regulations are closely coordinatea,

especially with respect to the regulation of generators

(shippers) and transporters (carriers).(see Appendix A).

In addition to the HMTR, there are many other regulations

which affect the transportation of hazardous waste. Title 46

concerns bulk shipment by vessel, including specifications for

the design, construction, and operation of vessels engaged in

such transport. To go further than this into other Titles

woula be to wander farther afield than is envisionea by the scope

of this paper.

the Materials Transportation Bureau (MTB) is an agency within the Research and Special Projects Administration of the DOT,

whose major responsibility is the promulgation of regulations

under the hazardous materials program ot· the DOT. Thus, the

MTB is responsible ror most of the regulations arrecting the

transportation of radwaste.

~her:de!·ini tion

of· what constitutes hazardous wastes is the

t·irst step in compliance with the HMTH. All other decisions

on packaging, transportation, and communications of hazards

rest upon the decision of how to classify the material or

waste. The statutory definition of hazardous materials under

the HMTA is a substance or material in

a quantity or form

which has been determined by the Secretary of Transportation

to be capable of posing an unreasonable risk to health and

property when transported in commerce, and which

has been so designated 2 3. This same definition has been adsafett~or

opted by the HMTR.

The HMTR have been amended recently (May 22~J 1980), and

specific reference is made to hazardous waste in the new regulations. Hazardous waste is defined as any material that is

subject to the hazardous waste manifest requirements of the EPA

as specified in 40 CFR Part 262 24 , or that would be subject

to these requirements absent an interim authorization to a

state under 40 CFR Part 123, Subpart F. Thus the definition of

hazardous waste under the RCRA regulations (40 CFR) and the

HMTR (49 CFR) are coordinated.

As a further example of the overlap and coordination between

the EPA and the DOT in this area, the RCRA regulations state

that before transporting hazardous waste or offering hazar-a . ~~-r-

.

.

dous waste for transport off-site, a generator must package

the waste in accordance with the applicable DOT regulations

on packaging 25.

A container to be used to ship hazardous materials must be

designed, constructed, packed and sealed in compliance with the

HMTR so that during transport there will be no release of the

materials into the environment. Part 173 also contains extensive requirements for specific hazard classes, and Subparts

C-0 of 173 contain over 200 pages on these classes.

Before transporting or orfering for transport off-site any

j,

hazardous waste, a generator must mark each container of 110

26

gallons or less with a warning as specified in the CFR • A

I'·

hazardous material transportation label is a color-coded sign

with a hazard warning word written upon it, attached to the

package or container containing the material. A DOT placard

is a rectangular color-coded sign with a warning written

upon it, identifying the material and the hazards associated

with it 27 • Placards are placed on carriers and certain containers, and serve to warn personnel involved in transport

and the public at large of the potential hazards with the

shipments. DOT regulations specif'y that each motor vehicle,

rail car, or freight container containing hazardous material

be placarded on all four sides (i.e. sides, front, and back).

Hesponsibilities for transporters of hazardous waste are

specified in both the RCRA regulations 28 ,and in the HMTR~ 9 .

In the event of a hazardous waste discharge, the HCRA regulations

require (1) immediate action, and (2) any cleanup action that

may be required3~ "Immediate action" connotes certain steps,

including the rollowing:

1. Take appropriate action to protect human health and the

-<Ill'\ f") I")~

UUt.1\..' 'U

environment,

2. Give proper notification, if required, to the National

Response Center, and

5.

~eport

in writing, as required, by the HMTR.

The major concern of the HMTR has been primarily human sarety and the protection of property. The revised DOT regulations,

which include hazardous waste, have also recognizea the chronic

risks to both human health and the environment posed by the

ttansport or hazardous waste. An important provision has been

the addition to the DOT regulations or hazard class ORM-E to

include hazardous wastes subject to the EPA (H~RA) regulationsj·t.

Discharge in the regulations refers to an accidental or

intentional spillage of hazardous waste. Discharge and spill-·

age are not derined in the HMTH, but reference is made to them3 2 •

The RURA regulations requnre a transporter to clean up any discharge that occurs during transport or take such actions as

may be required or approved by the appropriate official.

The results or the c leanup must be such that the discharge

no longer represents a hazard to health and the environment 33 •

The DOT regulations include additional notice

requiremen~s

for

hazardous materials incidents. Each carrier who transports such,

including hazardous waste, shall report to the DOT in writing

within 15 days of discovery of an incident that occurs during

the course of loading (including loading, unloading, or temporary storage) 34 •

Part 177 provides general information and regulations on

the transportation of hazardous material by public highway.

These regulations apply to all private, common, and contract

carriers by motor vehicles transporting hazardous materials

as defined by DOT "Regulations for Transportation of Hazardous Neteriele ~ ~•nq and ~hli~ Rail Freight Express and

Baggage Services and by Motor Vehicle (Highway) and Water"35.

Shipments by the Department of Def'ense and .k.tomic Energy Commission are exempted from these regulations, provided equal or

better protection is supplied in packaging and shipment.

Having discussed generally the broad scope of the regulations

affecting the transportation of radwaste, and the interrelationships of· the OOT and the EPA in the area, we shall now

turn to a brief discussion of some of the safety problems

found in this area.

Each pressurized water reactor {PWR) produces 64 spent fuel

assemblies each year; one truck carries one fuel assembly. Each

such shipment thus contains ten times the amount of cesium of

one Hiroshima atomic bomb3 6 • Cesium is a strong gamma emitter,

and it concentrates in shellfish and human muscle tissue and

gonads. Cesium's release into the environment would follow from

a loss-of-coolant accident. That is, if an accident causes

coolant to escape from the shipping cask, and if the spent fuel

assembly were not sufficiently cooled, the assembly could heat up

to the temperature at which cesium becomes volatile and boils

off. The regulations alluw a spent fuel assembly to become

this "hot". Cesium could then escape the cask, causing human

fatalities and contaminating a large land area ror long periods

of time. If 10% of the cesium in a shipment were released, it

would equal the amount of cesium in one Hiroshima bomb1 7 • These

are a lot of "ifs", "coulds", and "maybe", but the f'act remains

that this type of incident is not entirely outside of the realm

of' possibility.

There also exists the possibility (and this Should come as

a surprise to noone in this day of mass recalls of everything

from automobiles to blow dryers) of defects in shipping casks.

- 11 ()03~3

In fact, defective shipping casks have been constricted~s.

Additionally, there is some question as;to the ability of the

DOT to thoroughly regulate hazardous substances. There are

20,870 container manufacturer/suppliers; the DOT inspected

261 of them in 1977 with 6 inspectors. There are 104,570

shipping facilities; DOT inspected 1,91? in 1977j9. As a

result, local and state governments have been forced into

regulating shippers thrmugh the control of routes, the time

of day when shipments can be carried, and the quantities of

materials or wastes.

We turn now to a consideration o1· liability tor nuclear

accidents. While most (if" not all) statutory and case law

deals with incidents or accidents at nuclear reactors \e.g.

Three Mile lsland), it is likely that the same rules and

principles will apply to transportation accidents as well.

The Price-Anderson Act 40 insulates the civilian nuclear power

industry from massive tort liability. In 1977, future civilian

development of nuclear was seriously threatened

when the U.S.

district court for the Western District of North Carolina declared the liability

limitation provision of the Act un-

constitutional41. However, the U.S. Supreme Court later overturned that decision in Duke Power Co. v. Carolina Environmental Study Group, Inc.4 2 •

In Carolina Study Group (the first case), the district

court held that the liability limitation provision violated

the due process clause of the fifth amendment and the equal

protection component of that clause 43 • The Supreme Court

reversed, applying a minimum standard of review. Duke Power is

an example of judicial deference to Congressional legislation.

The Price-Anderson Act currently pr~vides for compensation in

the case of "nuclear incidents" involving activities licensed

by the NRc 44 • The statute would probably (although it does

not do so expressly) cover injuries which arise during the

transport phase of the nuclear fuel cycle, but limits total

compensation to 560 million dollars per incident, which may

be inadequate in light of today's trends of high inflation.

Finally, we shall consider the issue of states' rights and

federal pre-emption of· those rights. Eighteen states have

claimed for themselves the authority to block federal decisions

which may not adequately safeguard against accidents, leakages,

spills, or operational failures involving the transportation,

storage, and use of nuclear materials. However, these

may run into

s~ates

trouble with the Supremacy Clause of the

u.s.

Constitution. The states' rights to impose conditions or

require prior consultation on potential waste disposal sites

within their respective jurisdictions can be challenged

in court, even in the absence of a federal solution (the absence of a federal solution never stopped the Feds before),

and in ract have been challenged success1ully bEfore.

In 19?4, Congress amended the Atomic Energy Ac~ 45 to allow

greater participation or private industry through a licensing

system4 6 • Later, Congress passed lEgislation giving the states

greater control over certain specific kinds of nuclear materials 47 •

The states' laws giving them a role in .:federal radwaste management vary, but virtually all purport to review and override

proposed t·ederal actions within their jurisdictions; but these

state laws may be pre-empted by federal authority established

under the Atomic Act as amended4 8 •

The pre-emption of the

A~A

was challenged by Minnesota in

the Northern States Power case 4'. Here, the court concluded

that the states' rightsuto regulate radiation hazards is specifically limited to those materials defined in section

~U21(b)

and does not extend to any other areas. Thus it would seam that

the courts woula tend to apply the strictest construction

possible when federal pre-emption of states' rights in the

nuclear and radwaste mangement area is challenged.

Opponents to state participation argue that enactment of

legislation giving the states more power in this area would result in all fifty states objecting to radwaste disposal facilities proposea for their jurisdictions. However, the states

are rejecting radwaste even in the absence of statutory authority, and this trend will, at the least, delay the development and implementation or a national radwaste management plam.

Footnotes

1. Lennemann, U.S. Atomic Energy Radioactive Waste Burial

Program, 9 Atom Energy L, J, 1, 25 (1967).

2. Wis L. Rev 1979 pp.

72s.s:~

3. Id,, at 726,

4. H. Krugman and F. von Hippel, "Radioactive Wastes: A Comparison

Ci~ilian

of Military And

Inventories", Science,

1~7

(1977):p.883.

5,Error.

6. 49 C,F.R. 173.58Y (j), (k) (1977).

7. supra n.2 at 733.

a. Id., at 741.

9. Cohen, Impacts

~Safety,

£!~Nuclear

Energy Industry 2ll Human Health

64 Am, Scientist 550, 556 (1976),

-----

1U, Comment, Policing Plutonium: !h! Civil Liberties Fallout, 10

Harv. C,R.-C.L, L. ftev, 369,

11, Weinberg, Social

-582-83

Institutions~

( 1972),

12, 10 C.F.R. 71, app. B (1975).

13. 20 Nucl, News 90B (Apr. 1977).

14. 49

u.s.c.

§102,

15.

I d., at

§

103.

16.

Id., at

§

106,

17. 42 U,S.C,J20'1 et seq ••

-

18,

Id., at 83003.

19. 49 C.F.R, 171.15, 171.16.

20,

Id., at 172 .1u1.

21, Id., at 174,175, 176.

22. Id., at 178, 179.

23. 49

24. I

u.s.a.

§§

103, 104.

003~!~

(1976),

Nuclear Energy,177 Sci. 27, 31

25. 40 C.F.R. 262.30, 49 C.F.R. 173, 178, 179.

26. 49 C.F.R. 172.304.

27. Id., at 172.5UO.

28. 40 C.F.R. 263.

~Y.

49 C.F.R.

171-17~.

30. 40 C.F.R. 263.30, 263.31.

31. 49 C.F.R. 171-173.

32. Id., at 171.15, 171.16.

33. 40 C.F.R.

34.

4~

~63.31.

C.F.R. •171. 16.

35. Id., at 177.802.

36. U.S. Department of Energy, "Monthly Energy Review", DOE/EIA

-U035/11 (November 1979).

37. M. Resnikoff, "Nuclear Wastes - The Myths and the Realities",

Sierra, pp.j2, 33, July/August 1Y80.

38. U.s. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, "In!'ormation Report to the

Commissioners", from W.J. Dircks, Director, Of.t"ice of Nuclear

Material Safety and Sareguards,

S~CY-79-~64

(April 16,

197~).

39. U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Commerce, Science, and

Transportation, "Hazardous Materials Transportation", Ybth

Congress, 1st seas., (April 1979), p. 80.

40. 42 U.S.C.

§ ~21U (1~76).

41. Carolina Environmental Study Group, Inc.,v. United States

Atomic Energy Commission,

u.s.

4~.

438

4~.

supra, n.b1 at

44. 42 U.S.C.

45. Atomic

46.

4~1

F. Supp.

~u~

(W.D.N.C. 1977).

59 (1978).

~~4-5.

§ 2U1~

~nergy

(i) (1978).

Act

or

1946, ch. 724, bU Stat.

4~ u.~.c. § ~u11 ~ ~··

--

47. Id., at ~U~1 (a) (1976).

000 ~~

..... -·

.._

. .

\

75~.

48. Id., at £01£ {1976).

49. 447 F.2d 1145 (8th Cir. 1971).

APPENDIX A

Relationship Between the RCRA Regulations and HMTR on Key Topics

Topics

Title 4U Regs

Title

4~

Definitions

26U.10

171 .8

Identification and listing of

261

17~

Regs

hazardous material and waste

Characteristics of hazardous

261.~U-

~61,~4

171 .8, 173

materials and wastes

Compliance with manifest system

262.~0

26~.2~,

to

17~,20?

and

~b3.~U,2b3.~1

Packagings and containers

262.~0

175,178, 179

Labelling Requirements

262.~1

172.4UU to

172.4?0

Marking requirements

262.)2

17~.3UU

to

17~.~5U

Placarding requirements

172.?Uu to

17~.588

Hazardous materials and waste

171.15

discharge inciaents

171.17

1;0