WHAT EFFECT SHOULD THE PLAINTIFF'S SUBSTANDARD

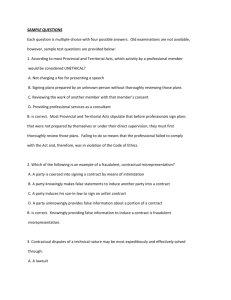

advertisement