Federal Jurisdiction: Thrust and Parry by E.

advertisement

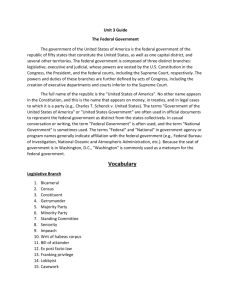

Federal Jurisdiction: Thrust and Parry by Thomas E. Baker · Federal jurisdiction is a fencing match, a contest that has its own special art and form . For every jurisdictional issue there is a thrust and parry. How and when to make those moves is what this article is all about. The object of our match is assumed: Storm the castle. Get into federal court and stay there. The problems in doing that lie in the very nature of federal courts and the fede ral government. Even though some federal judges do not act that way, they all sit on courts of a limited sovereign. Limited sovereigns have limited power, and their courts have limited jurisdiction. That is the key to our subject. Before a federal court may hear a case, it has to pass two tests. The case must fall within the scope of Article III of the Constitution and within the scope of some particular jurisdiction enabling act of Congress. If the case fails either test, the federal court does not have jurisdiction. What is more, the presumption is against jurisdiction. The party invoking federal power must rebut that presumption . Not only can the other side resist jurisdiction, but the court has the obligation to raise jurisdictional issues on its own motion. Even the party invoking federal jurisdiction can later challenge that jurisdiction when the result does not satisfy him. See generally C. WRIGHT, LAW OF FEDERAL COURTS Sec. 7 (4th ed. 1983). In a system in which every actor must invoke the jurisdictional bar, is it any wonder that so many suits fail at the threshold? So here we are at the castle gate, sword in hand. Whether we get in depends on the answer to two questions: Does the federal court have the power to hear the case? Should it exercise that power? Those are the questions, but our focus is going to be on the thrusts and parries involved in answering them . THRUST: The plaintiff has no standing. PARRY: Standing rarely becomes an issue in private litigation . The victim of some contract breach or tort brings suit, The author is Professor of Law at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. and his standing to raise the claim is obvious. In public law litigation, by contrast, when a plaintiff challenges some governmental action, whether the person bringing suit is more than a bystander is a difficult and important question. Public law standing doctrine separates taxpayer plaintiffs from those who are more closely connected with the controversy. That does not mean taxpayers cannot have standing. They can, but it is difficult. A taxpayer has standing as a taxpayer if the federal action being challenged allegedly exceeds a specific constitutional limit on congressional spending power. The category is narrow and is controlled by constitutional principles, but it is there. For example, a taxpayer can attack a program of federal religious school aid as a violation of the establishment clause but cannot challenge the same program under either the due process clause or the Tenth Amendment. Local plaintiffs, however, may claim standing more easily as taxpayers challenging local expenditures. This approach should not be overlooked. A nontaxpayer challenging a government action can have standing, if he shows an actual or threatened injury that can be redressed by a favorable decision. Injury, causation, and redressability are all that the Constitution requires. But nontaxpayer standing seems more difficult to establish these days. See Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Inc., 454 U .S. 464 (1982). Now distinguish the nonconstitutional, prudential principles of standing. They are frequently invoked (and almost as frequently excused). Because they are creatures of judicial restraint, a court feeling unrestrained may pay them only lip service. When they are the thrust, the parry may be either that they are satisfied or should be excused. There are three prudential principles of standing: First, the plaintiff's own concern must come within the zone of interest protected by the statute invoked in the case. The plaintiff can find this requirement in legislative intent or use the requirement's inherent ambiguity to make a bold assertion that the requirement is satisfied. Second, courts will not hear generalized grievances com- monly shared by everyone. The parry is to convince the court that the plaintiff's grievance is special. Third, a prudential rule allows a plaintiff to assert only his own, and not some third party's, legal interests. The parry is the exception allowing representational standing - an exception of near-swallowing proportions. To say that the rule has been markedly relaxed may be an understatement. Any person involved in a relationship that is affected by the challenged government action most likely can proceed under the representational standing theory. Litigation surrogates also may be created, as when a not-for-profit corporat ion sues on behalf of its members. (And now an important point that keeps popping up throughout federal jurisdiction: The exceptions to the rules have themselves become ways into federal court. A good proceduralist uses them to advantage.) THRUST: The case is moot. PARRY: The moot ness doctrine is not a talisman requiring dismissal upon invocation . There is almost always room for the argument that something remains for a judgment to accomplish - there is a live case or controversy. If that does not work, a common exception allows an otherwise moot case to survive if the controversy is "capable of repetition, yet evading review ." That means if the challenged action is of such brief duration as to be completed before the ordinary run of litigation and there is a reasonable likelihood that the plaintiff will suffer the same injury again , the case may go on. THRUST: There is no personal jurisdiction over the defendant. PARRY: Put aside the metaphysics of in personam, in rem, or quasi in rem jurisdiction. Forget for now about personal service, domicile, or consent and questions about state of incorporation, doing business, or presence. Those are all commonplace. What about jurisdiction by default? There is always jurisdiction to determine jurisdiction. A federal court has the inherent power to consider whether there is jurisdiction over both subject matter and the person. Subject-matter jurisdiction is both constitutional and statutory and cannot be garnered by consent, waiver, or estoppel. But in personam / jurisdiction is part and parcel of due process's liberty. Entering a special appearance to contest personal jurisdiction permits that determination . However, the court may enter a discovery sanction order establishing personal juris- diction over an obstreperous party who has frustrated discovery efforts to establish jurisdictional facts. Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(b)(2)(A); Ins. Corp. oflrelandv. CompagniedesBauxites de Guinee, 456 U.S . 694 (1982). This strategy may be too much of a long shot for a plaintiff to pursue, but a defendant resisting jurisdiction and discovery should take care not to resist too much . THRUST: There is no independent jurisdiction to support joining a particular claim or party. PARRY: Once there is a federal jurisdictional anchor, you can append claims and parties without an independent basis under the related doctrines of ancillary jurisdiction and pendent jurisdiction. These doctrines are too complicated to discuss fully here. I mention them because they allow claims and parties into federal court that otherwise would never be permitted. The underlying policy is that if a federal court has some jurisdiction over part of a dispute, it can reach beyond its jurisdiction and decide related aspects over which there is no independent jurisdiction. In short, the power to decide a case or controversy is the power to decide the whole dispute . Pendent jurisdiction and ancillary jurisdiction can apply in diversity and federal question cases and apply to claims and parties that neither jurisdiction reaches . Ancillary jurisdiction applies to claims and parties joined after the complaint by parties other than the plaintiff. Pendent jurisdiction applies to claims raised by the plaintiff in the complaint. C. WRIGHT, LAW OF FEDERAL COURTS, Sections 9, 19. The liberal joinder provisions in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure allow these two kinds of auxiliary jurisdiction. You do not need complete diversity for a compulsory counterclaim under Rule 13(a), even when additional parties are brought in und~r Rule 13(h), or in an intervention as of right under Rule 24(a), when a third party is impleaded under Rule 14 or when a cross-claim is asserted under Rule 13(g), as all such claims may fall under the ancillary power. A federal court also can decide a pendent state law claim without independent jurisdiction, even after the federal claim is dismissed on the merits. And, at least when federal question jurisdiction is exclusive, a federal court may even allow joinder of a pendent party. An attorney who can get one foo t in the federal courthouse door may get all the way in and even drag others along. THRUST: The federal court should abstain. PARRY: The abstention doctrine is really five more or less distinct categories in which the federal court declines to proceed even though there is jurisdiction: First, the Pullman abstention doctrine allows a federal court to refrain from deciding a constitutional challenge to state conduct if there is an unsettled question of state law that may control and avoid the federal issue. Railroad Comm'n v. Pullman Co, 312 U .S. 496 (194 1). Second, the Burford abstention doctrine generally allows the federal court to defer to a state's administration of state affairs and avoid unnecessary conflict. Burford v. Sun Oil Co, 319 U.S . 315 (1943). Third, the Younger doctrine (a variant of Burford) requires that a federal court abstain from granting declaratory or injunctive relief when a state criminal proceeding or its equivalent is pending against the federal plaintiff. Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971). Fourth, certification is when a federal court refers state law questions to the highest court of the state under some state statute or state court rule. Clay v. Sun Ins. Office Ltd., 363 U.S. 207 (1960) is a good example. Fifth, (a category of doubtful validity but mentioned for the sake of completeness) is the federal discretion to stay or dismiss a federal case simply because a parallel case is pending in state court. It may be unfair to mention these doctrines and then weakly finesse my parry by observing that they are so subtle and full of nuance as not to be readily captured here. So I am unfair. A few observations , however, are in order. The pending state court doctrine is invoked from time to time in wildcat fashion by lower courts. It must be of dubious validity considering recent Supreme Court opinions. See Moses H . Cone Memorial H osp. v. Mercury Constr. Corp., 460 U.S. 1 (1983). Certification, the fourth variation, applies in diversity cases. It is a creature of the state rule and merely stays the federal proceeding while the state court answers the question. Everythi ng el se rema ins federal. The first three doctrines - the Pullman, Buford, and Younger hybrids can be costly in time and lost federal opportunity . Their application sounds in abstractions of constitutional law. The degree o f certainty of the state law may control. The federal court may grant interim relief while you pursue state proceedings . Later federal proceedings, including Supreme Court review of state court decisions affecting federal rights, should be contemplated during the state court sojourn . All right. That is enough to show that these doctrines are indeed complex - to the point of bei ng downright metaphysical. That, however, is also their vulnerability. (And that is another secret of much federal jurisdiction. Incantation and ritual can move the court to act or not to act. Steeped in their lore, a persuasive advocate often can convince the federal court to go on. My best, last advice is to research and reflect, never losing sight of the federalism concerns that undergird the area of abstention.) T HRUST: There is no diversity jurisdiction over domestic relations cases. PARRY: For more than 100 years, that has been th'e announced rule. Traditionally, diversity plaintiffs have been denied a federal forum in domest ic relations suits for divorce, property settlements, alimony, and child custody. Nothing in the Constitutio n requires this approach . Iniead, this has been a judge-made except ion, which recently has shown signs of narrowi ng. Recent cases have been inconsistent and unpredictable, in part because the courts do not seem willing to define the boundaries of the exception, or capable of doing so. An opportunistic proceduralist views this confusion as an opening into federal court. Some recent decisions have held that cases between family members, sounding in tort or contract, can be tried in federal court if the issues do not depend on familial relations and the suit is not a transparent effort at avoiding the rule. If that sounds fuzzy, you are right. You cannot easily determine just when a claim is inside or outside the exception. One recent decision illustrates the wavering nature of the line. A man's tort action to recover damages from his ex-wife for kidli:>pping their child was inside the diversity jurisdiction line, while his request for injunctive relief to enforce a childcustody decree was outside and barred from federal court. Bennett v. Bennett, 682 F.2d 1039 (D.C. Cir. 1982). TH RUST: Federal courts may not hear probate matters. PARRY: The analysis is like the one for domestic cases . Nothing in the Constitution or in the statute necessarily requires this second judge-made rule. There seems to be even more room for an exception here. Professor Wright says that the rule "is far from absolute" and depends on "unclear distinctions of the utmost subtlety." C. WRIGHT. LAWOFFED· ERAL COURTS, Sec. 25 at 145 (4th Ed. 1983). Again, some recent decisions seem to be narrowing the bar to jurisdiction. There is agreement that "pure" probate matters are outside federal diversity jurisdiction. A federal court may not take control of property in a state court's custody, may not invoke a general jurisdiction over the probate, and may not otherwise interfere with the state court's probate proceeding. Once the suit may be characterized as not involving "pure" probate, the issue becomes whether the federal action will interfere unduly with the state probate proceedings. The courts have developed two ways to evaluate this interference. One approach focuses on the nature of the claim. If the plaintiff asks the federal court to rule on the validity of the will, there is interference, and the claim is barred. I f the plai nti ff admits the wi ll's validity and merely claims a share in the distribution, there is no interference, and the federal court can hear the claim. A second, more common, approach examines the procedures as if the federal claim had been brought in state court. If you could only try the claim in the state probate court, interference would be established, and the federal court would refuse to exercise jurisdiction. But if you could enforce the claim in a state court of general jurisdiction, the federal court would entertain the suit. Either approach (or some combination) allows for significant federal jurisdiction despite the general rule . See generally Rice v. Rice Found, 610 F.2d 471 (7th Cir. 1979). THRUST: A state is not a citizen for purposes of diversity and may not be sued under that jurisdiction. PARRY That is the well-established rule. Also well established is that a state's political subdivision is a citizen of that state for diversity purposes unless it is the state's alter ego (the state is the real party in interest as determined by state law). A diversity suit may proceed against a state agency that is established to be independent, separate, and distinct from the state. Naming the state agency as a party may be the ticket into federal court. THRUST: A party, "by assignment or otherwise, has been improperly or collusively made or joined to invoke the jurisdiction ... . " PARRY: In those words, 28 U.s.c. Sec. 1359 prohibits manufacturing diversity. When the transfer is absolute and the assignor retains no interest, however, the citizenship of the assignee controls, and there is no impropriety or collusion. Kramer v. Caribbean Mills, Inc., 394 U .S. 823, 828 n. 9 (1969). A nondiverse assignor might sell a liquidated claim to a diverse assignee, but that strategy is limited to negotiable claims. A party can change his own domicile to another state and gain jurisdiction, even if the move is motivated solely by a desire to creatc jurisdiction . Morris v. Gilmer, 129' J.S . 315 (1889). Most claims , however, are not so marketable and do not justify moving to another state. Short of those strategies, the only way is to overcome Sec. 1359. Interestingly, Sec. 1359 is as effective in creating jurisdiction as it is in defeating it. The collusion issue commonly arises in cases started by nonresident fiduciaries, such as ad ministrators or guardians. Two approaches have emerged. Some courts apply a motive or function test to the appointment and consider: (I) the relationship between the representative and the represented person; (2) the representative's powers and responsibilities; (3) whether the diverse representative is a logical choice; and (4) the nature of the suit. Other courts apply a substantial stake test that deemphasizes motive and considers how much of an interest the representative has in the outcome of the suit. In cou rts following this second approach, the advocate might structure the assignment as to strengthen an anticipated claim of diversity. THRUST: The Declaratory Judgment Act is not a grant of jurisdiction to the federal courts. PARRY: I have no quarrel with that truism , but I suggest that invoking the court's discretion under the act can be an important part of an effective jurisdiction strategy. Generally, the declaratory judgment statute allows earlier access to federal court when neither party may yet be able to sue for a coercive remedy, so long as there exists a genuine case or controversy. The difficulty to be turned to advantage involves the rigid requirement that the federal question appear well-pleaded on the face of the complaint, a requirement that dates from the forms of action era. See generally C. WRIGHT, LAW OF FEDERAL COURTS, Sec. 18 (4th Ed. 1983). When the plaintiff sues on an affirmative federal right, he obviously satisfies the well-pleaded complaint rule, as when an owner of a patent seeks a declaration of validity and infringement rather than suing the defendant for damages. But suppose that the request is for a declaration that the opposing party does not have a federal right. Before the creation of the declaratory remedy, that complaint only would have anticipated a federal question defense and would not have satisfied the well-pleaded complaint rule. Today, the defendant in the patent example can seek a declaration that he has not infringed or that the alleged owner does not hold a valid patent. This us·e of the act does allow some plaintiffs into federal court who otherwise could not get there. Another creative use of the declaratory judgment involves a plaintiff asking the court to declare that federal law protects him from a nonfederaI claim by the defendant. Suppose one party to a contract asks for a declaration that a federal statute enacted after the contract excuses him from performing the contract and preempts any suit for breech by the other party. As you have begun to expect, there are two approaches to the problem. The narrow approach requires dismissal. If the plaintiff in the declaratory judgment waited to be a defendant for breaching the contract, the federal question would be a defense to the case. And that would mean no federal question because it was not in the claim. The broader (and seemingly viable) view would allow the artful pleading. Some cases suggest that a party who claims that federal law controls can institute a federal declaratory judgment action, even though a coercive suit by the party relying on state law could not be brought in or removed to federal court. Strategy thus almost overtakes jurisdictional principles as the party claiming a federal preemption will seek to avoid an unsympathetic state forum by bringing a declaratory judgment action in federal court. Compare Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 103 S. Ct. 2890, 2899 n. 14 (1983) with Franchise Tax Bd. v. Construction Laborers Vacation Trust, 103 S.Ct. 2841, 2850-55 (1983). (And no one said federal juris(Please turn to page 59) which describes a certain kind of pain as well as it can be done. The little ills of life are the hardest to bear, as we all very well know. But what would the possession of a hundred thousand a year, or fame, and the applause of one's countrymen, or the loveliest and best-loved woman - of any glory, and happiness, or good fortune, avail to a gentleman, for instance, who is allowed to enjoy them only with the conditions of wearing a shoe with a couple of nails or sharp pebbles inside it? All fame and happiness would disappear and plunge down that shoe. All life would rankle around those little nails. ForUDl Shopping (Continued from page 22) became the new forum. The jury verdict - $84,000. The lesson: Some forums cost more than others. Make certain you buy a ticket to the right event. I have been discussing forum shopping practiced within the familiar arenas of courts and court processes. I suggest that, for the thoughtful lawyer , new horizons are emerging, particularly for commercial clients who want the latest fad. Consider this scenario. Your client, CEO Corporation, comes with a claim against Macro Ego Incorporated . It comes reluctantly, for business people are ever embarrassed when their documentation has erred; their wonderous negotiating talent has been elusive. Then in -house counsel (for all their budget skills) say, "We'll have to go to our outside firm and discuss litigation." (No one discusses suing - such language is declasse.) You meet: CEO's president, general counsel, and you. "Litigation - you want it?" you ask. "Sue Macro Ego? Do you think it is advisable? It will most assuredly be expensive. " CEO's president is impressed with such wisdom, especially coming from a lawyer. "What are our choices? I need to make my decision-tree analysis," he tells you. You reply, "Well, there is federal court or state court, here or in New York, but, as you well know, courts and trials have their failings. Tell me about Macro Ego and your claims against it." You soon learn that your client is into every aspect of his company's business and shares with his general counsel a certain paranoia about courts and lawyers (except the docile in-house variety). You also learn that the claim of CEO Corporation, while not rotten, does have some odor to it - which an astute judge might detect. And as with many things a trifle spoiled, time will not improve these claims. A quick check indicates that Macro Ego has publicly committed itself to alternative dispute resolution. This option (nonviolent combat in the eyes of your client) is available. Instinctive courthouse logic tells you that when two companies are committed to resolving disputes alternatively, they do not want either side to go away mad. It leaves too many options for the la·vyers - next time. And for a case that does not pass an early smell test, this could make sense. "Or we could do a minitrial for you, Mr. CEO, and for Macro's president or the people you arid he designate. Then you as businessmen could work it out, better than uninformed lawyers." Again lea ving the ball in the client's court, and if the client can't hit it, there is always the lawyer's home ground - the courthouse - to resume play. Mr. CEO is interested. "Anything else?" "Well, we could rent ajudge ." (Now that is an attention-getter.) And the list goes on - arbitration, mediation, prefilingjudicial conferences. The happy result is that you find a forum with a proclivity for middle-of-the-road decisions. Your client becomes directly involved. A bad case is lodged in a good forum - and outside counsel appears the wiser. Yes, the horizons have widened. The skilled litigation communicator (formerly called a trial lawyer) will soon master this new terrain. Now it is not only avoiding Judge Curmudgeon, Judge Miserly, or the county court- house, there is the client's interest and personality, not to mention the merits of its disputes, your adversaries' disposition toward law, the nature of the claim, and a variety of forums, some maybe not even devised yet. The more things change, the less change there may be for the astute forum shopper, ever looking for a good bargain. ~ederal Jurisdictiol1 (Continued from page 20) diction could not get satisfyingly intricate.) THRUST: Federal law creates a duty without expressly providing a remedy, and, consequently, there is no federal question. PARRY: If a remedy may be implied, there is federal question jurisdiction. Such a remedy may be implied directly under the Constitution or under some relevant statute. The important jurisdictional point is that the implied remedy simultaneously and necessarily creates federal question jurisdiction over the newly created private cause of action. While the constitutional category is somewhat limited to the text, in our highly regulated economic system there are many statutes from which to choose. Four factors generally indicate when a statute implies a remedy: (1) whether the plaintiff is a member of the class sought to be protected by the statute; (2) whether there is any indication of legislative intent to create or deny a private remedy; (3) whether a private remedy would further the legislative purpose; (4) whether the cause of act ion is one traditional to state law, so that a federal implication would be inconsistent. Cort v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66, 78 (1975). See also Davis v. Passman, 442 U .S. 228 (1979) (Constitution). Most important is divining a congressional intent to establish a private right of action from the entrails of legislative history. That is getting harder to do, since more recent Supreme Court decisions suggest a hardening of attitude against implyi ng a private right from a public statute. The plaintiff should hope for a precedent from the earlier period of willingness to implicate, since new ones seem so hard to get. Nevertheless, implying a private cause of action is still possible, and some federal judges may be more willing than others to try it. THRUST: There is no federal question arising under either the Constitution or any federal statute. PARRY: If not the Constitution or a federal statute, then how about the federal common law? That federal common law exists, we may accept as an article of faith. What it is and when it applies are more difficult questions. Here are three possibilities for finding federal common law: First, some situations require a federal common law to protect a uniquely federal interest when state law would be in conflict. Second, fede ral statutes so dominate some situations that federal common law seems a necessary concomitant. Third, there are some situations in which the federal and national concern is inherently superior, and federal law must control. But what about jurisdiction? When federal common law does apply, federal jurisdiction follows necessarily. City of Evansville v. Ky. Liquid Recycling, Inc., 604 F.2d 1008 (7th Cir. 1979). THRUST: There is no general federal question jurisdiction. PARRY: Assuming that is so, the attorney should look over the menu of special federal question jurisdiction statutes. Between 1875 and 1980, the general federal question statute carried a jurisdictional amount requirement. Consequently, Congress enacted a plethora of special statutes without an amount requirement which are spread throughout Chapter 85 of Title 28 and beyond . A partial list of examples from Title 28 discloses their breadth: Sec. 1333 (admiralty), Sec. 1337 (statutes regulating commerce), Sec. 1338 (patents), Sec. 1352 (federal bonds), and Sec. 1346 (United States as defend~nt). Additionally, specific grants of j\uisdiction are sprinkled throughout the substantive statutes . Any of them can be a way into federal court. THRUST: There is a statute depriving the fede ral court of jurisdiction. PARRY: Argue that this case does not fall within the statutory prohibition. Two provisions are commonly in- voked. See C. WRIGHT, LAW OF FEDER· AL COURTS, Sec, 51. First, 28 U .S.c. Sec. 1342 deprives the district courts of jurisdiction to enjoin the effect of any order of a state agency affecting public utility rates if, and only if: (I) jurisdiction is based on diversity or a federal question arising under the Constitution; (2) the challenged rate order does not frustrate interstate commerce; (3) the rate order was preceded by a reasonable notice and hearing; (4) there is an effective remedy in state court. Second, 28 U.s.c. Sec. 1341 prorubits an injunction against the assessment or collection of any state tax if an effective remedy exists in state court. The very strength of such provisions can be used against their application. Their particularity means that if any of the identified conditions is missing, the statute will not apply. Some research leavened with persuasion can show how the statute will not keep the case out of federal court. What do we make of all these thrusts and parries? Federal jurisdiction is complicated, sophisticated, and theoretical. We should expect that from a legal specialty that deals with such important issues of federalism. The litigator must be equal to that chz.llenge. The crafty proceduralist uses that sophistication and complexity to advantage. In thi~, as in the' rest of the trial arts, one must strive for mastery. One of Aesop's fables best describes what is at stake: A swallow hatched her brood under the eaves of a Court of Justice. Before her young could fly, a serpent crept out of his hole and ate all the nestlings. When the poor bird returned and found her nest empty, she began a pitiable wailing. Another swallow suggested, by way of comfort, that she was not the first bird who had lost her young. 'True,' she replied, 'but it is not only for my little ones that I mourn, but that I should have been wronged in that very place where the injured fly for justice.' A lawyer looking to federal court may resemble our swallow. He brings his client's suit in federal court seeking a more just justice. Principles of federal jurisdiction, however, may play the role of the serpent. Sometimes, all is lost without even the opportunity to argue the merits of the cause. But there are some special ways to get in and to stay in federal court. Use them to help build your nest out of the serpent's reach . Conlpare Courts (Continued from page 16) have to write, When you dismiss the case, you have to write, or at least make oral findings . In the state court, you just say, "judgment for the defendant" or "motion granted," and then the appellate court would look at it, would look at the briefs, review the law, and make a determination about whether the motion should have been granted or denied. But I can understand the purpose behind the federal rule . There are reasons - salutary reasons - for making findings and conclusions. For res judicata purposes, we want to know the reasons; we don't want to guess at the results in a case. The rule also has the effect of putting the judge's feet to the fire, so to speak. It forces a judge to give , reasons for a decision. The salutary reasons for the rule are, however, often outweighed by the time required to write. We have a litigation explosion in this country. I think it makes more sense to make general findings and cite a case than to get to the point where you get so backlogged because you're overly worried about justifying your decision with a lengthy written opinion. In some cases, especially when a judge is very familiar with the law and facts, I believe the requirements of Rule 52 should be relaxed, Take, for example, the Shakman cases in my court. [Cases brought pursuant to a consent decree that prohibits the City of Chicago from firing or harassing public em· ployees for political reasons.] Because I handle so many of them, I can rattle them right off, make oral findings, and the case is over right after the trial. In these cases, I feel a prompt ruling is more important than a scholarly opinion. And in personal injury cases, the litigants prefer a quick ruling to an opinion. But there are precious few of those cases,