hope abandon I

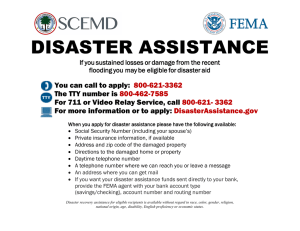

advertisement

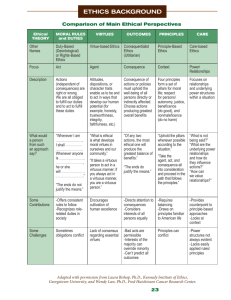

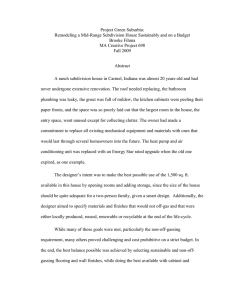

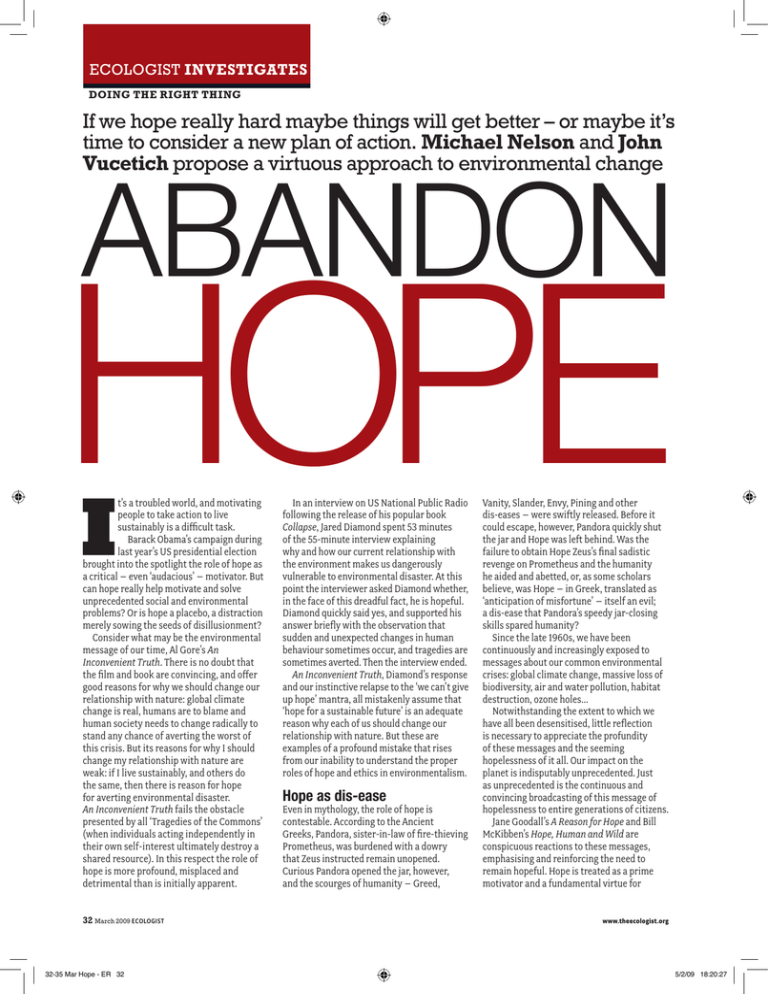

ECOLOGIST INVESTIGATES doing the right thing If we hope really hard maybe things will get better – or maybe it’s time to consider a new plan of action. Michael Nelson and John Vucetich propose a virtuous approach to environmental change abandon hope I t’s a troubled world, and motivating people to take action to live sustainably is a difficult task. Barack Obama’s campaign during last year’s US presidential election brought into the spotlight the role of hope as a critical – even ‘audacious’ – motivator. But can hope really help motivate and solve unprecedented social and environmental problems? Or is hope a placebo, a distraction merely sowing the seeds of disillusionment? Consider what may be the environmental message of our time, Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. There is no doubt that the film and book are convincing, and offer good reasons for why we should change our relationship with nature: global climate change is real, humans are to blame and human society needs to change radically to stand any chance of averting the worst of this crisis. But its reasons for why I should change my relationship with nature are weak: if I live sustainably, and others do the same, then there is reason for hope for averting environmental disaster. An Inconvenient Truth fails the obstacle presented by all ‘Tragedies of the Commons’ (when individuals acting independently in their own self-interest ultimately destroy a shared resource). In this respect the role of hope is more profound, misplaced and detrimental than is initially apparent. 32 March 2009 ECOLOGIST 32-35 Mar Hope - ER 32 In an interview on US National Public Radio following the release of his popular book Collapse, Jared Diamond spent 53 minutes of the 55-minute interview explaining why and how our current relationship with the environment makes us dangerously vulnerable to environmental disaster. At this point the interviewer asked Diamond whether, in the face of this dreadful fact, he is hopeful. Diamond quickly said yes, and supported his answer briefly with the observation that sudden and unexpected changes in human behaviour sometimes occur, and tragedies are sometimes averted. Then the interview ended. An Inconvenient Truth, Diamond’s response and our instinctive relapse to the ‘we can’t give up hope’ mantra, all mistakenly assume that ‘hope for a sustainable future’ is an adequate reason why each of us should change our relationship with nature. But these are examples of a profound mistake that rises from our inability to understand the proper roles of hope and ethics in environmentalism. Hope as dis-ease Even in mythology, the role of hope is contestable. According to the Ancient Greeks, Pandora, sister-in-law of fire-thieving Prometheus, was burdened with a dowry that Zeus instructed remain unopened. Curious Pandora opened the jar, however, and the scourges of humanity – Greed, Vanity, Slander, Envy, Pining and other dis-eases – were swiftly released. Before it could escape, however, Pandora quickly shut the jar and Hope was left behind. Was the failure to obtain Hope Zeus’s final sadistic revenge on Prometheus and the humanity he aided and abetted, or, as some scholars believe, was Hope – in Greek, translated as ‘anticipation of misfortune’ – itself an evil; a dis-ease that Pandora’s speedy jar-closing skills spared humanity? Since the late 1960s, we have been continuously and increasingly exposed to messages about our common environmental crises: global climate change, massive loss of biodiversity, air and water pollution, habitat destruction, ozone holes… Notwithstanding the extent to which we have all been desensitised, little reflection is necessary to appreciate the profundity of these messages and the seeming hopelessness of it all. Our impact on the planet is indisputably unprecedented. Just as unprecedented is the continuous and convincing broadcasting of this message of hopelessness to entire generations of citizens. Jane Goodall’s A Reason for Hope and Bill McKibben’s Hope, Human and Wild are conspicuous reactions to these messages, emphasising and reinforcing the need to remain hopeful. Hope is treated as a prime motivator and a fundamental virtue for www.theecologist.org 5/2/09 18:20:27 illustration: getty images environmental ethics. Hope is expected to encourage behaviours that – if they gather enough critical mass – might avert profound environmental disaster. Hope for a sustainable future is supplied as the fundamental reason for why I should change my relationship with nature: if I live sustainably, and others do the same, there is hope – and one should never give up hope – that we will avert environmental disaster. Hope may, however, ironically, deteriorate motivation to live sustainably: I have little reason to live sustainably if the only reason to do so is hope for a sustainable future. Why? Because every other message I receive suggests that disaster is guaranteed, and the reasons to think that if I live sustainably enough others will do the same are unconvincing. But isn’t attacking hope as mean-spirited as stealing Tiny Tim’s crutch? Wouldn’t you just as readily choose hell over heaven as abandon hope for… what? Despair? It’s an understandable objection, but ‘Hope is seen as a prime motivator but it may, ironically, deteriorate our motivation to live sustainably’ www.theecologist.org 32-35 Mar Hope - ER 33 misplaced. For example, what about the young man who hopes to become a pro basketball player, neglects his education and never makes it to the NBA? Or the terminally ill patient who hopes to mend broken relationships and do what she always wanted to do, but postpones these activities because she hoped to live? These people were hopeful (i.e. believed in a certain outcome) when they should have merely acknowledged their unfulfilled desire. The failure to distinguish between hope and desire in cases like these is not merely delusional, it is detrimental. It is true that, sometimes, unexpected fortune is realised mysteriously or inexplicably when a person is hopeful – the cancer patient may suddenly go into remission. Even in the realm of social behaviour, unexpectedly good circumstances arise. For example, attitudes about smoking ECOLOGIST March 2009 33 5/2/09 18:20:40 ECOLOGIST INVESTIGATES doING ThE rIGhT ThING To hope or not to hope? ACTION WHAT WE HOPE WILL HAPPEN HOPE’S UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES VIRTUOUS ACTION – THE ALTERNATIVE Reduce,reuseand recycle(R3) R3giveshopeforasustainable future,butonlyifmostother peoplerecycle. HopegivesmelittlereasontoR3; Idon’tbelievemyactionswillresult inasustainablesocietybecausetoo fewothersR3. Theneedsanddesiresofother humansandnon-humansoutweigh theplanet’slimitedresources. Reducing,reusingandrecyclingare kindsofsharing;itisvirtuousto shareevenifnobodyelsedoes. Reducefossil-fuel consumption Youshouldreduceyourfossil-fuel consumptionbecausedoingso giveshopeforpreventingworsened climatechange,butonlyifmost otherpeoplereducetheiruse. Hopegivesmelittlereasontodo thisbecausethereisgoodreason toexpectworsenedclimatechange regardlessofwhetherIreduce fossil-fuelconsumption. Drivingless(andwalkingmore) promotespersonalhealth.Warswill be(andarebeing)foughtoveroil.You shouldreducefossil-fuelconsumption becauseitisinherentlyvirtuousto promotepersonalhealthandnotwar, evenifnobodyelsedoes. Reducerelianceon productsthatuse pesticides(e.g.buy organic)orotherwise needlesslydestroy habitat Youshouldreduceyouruseofsuch productsbecausedoingsogives hopeforavertingcatastrophic environmentaldegradation,butonly ifmostotherpeopleactsimilarly. Hopegivesmelittlereasonto reducerelianceonsuchproducts; catastropheshouldbeexpected becauseothersarenotactingas youareaskingmeto. Youshouldreduceyouruseofsuch productsbecauseitisinherently virtuousnottoruinresourcesthat othersneed,evenifyouaretheonly onetorefrainfrombeingruinous. Beanenvironmental activist Youshouldbeanenvironmental activistbecausedoingsogiveshope forasustainablefuture,butonlyif youractivismchangesthelivesof enoughotherpeople. Hopegivesmelittlereasontobean environmentalactivistbecause otheractivistsdonotseemtobe changingthelivesofenoughothers, whyshouldIexpectmyactivism todoso? Youshouldbeanactivistbecauseit isinherentlyvirtuoustoshowothers whatcountsas,andhowtolive,a virtuouslife.Doingsoisvirtuous evenifyouractivismchangessome people,butnotenoughtoavert futuredisaster. in the US changed suddenly and unexpectedly in the late 1980s. So, miracles and unexpected good fortune occurs from time to time. Fine. But is this good reason to think that if we continue destroying our environment, we can expect (hope) that things will mysteriously work out okay? A profound contradiction It could be that this is all obnoxiously Cartesian; that we are disregarding the real effects of the human spirit and attitude on the physical world. We know anecdotally and scientifically that positive attitudes promote human health: calm attitudes reduce blood pressure, which reduces risk of heart disease. Scientists have discovered that meditation can cause cancer remission, due to the mind’s influence on the immune system. Hopeful attitudes certainly inspire some of us to live at least a bit more sustainably. However, with the same certainty, we know that hope does not inspire most of us to live sustainably. What we need are environmental leaders with whom their presumed target audience – those who are not living sustainably – can empathise. Like it or not, deserved or not, many such individuals are unsure about how environmental leaders differ from authorities such as presidents who lie about reasons for war, or cardinals who turn a blind eye to paedophilic priests. To this audience, environmental leaders deliver an incredible message, in three parts: 1) scientists give good reasons to think profound environmental disaster is eminent; 2) it is urgent that you live up to a challengingly high standard – sustainability; and 3) the reason to live sustainably is that doing so gives hope for averting disaster. The most conspicuous element of the message received may be its apparently profound contradiction – be hopeful in a hopeless situation. Given a predisposition ‘If hope for averting environmental disaster isn’t the right reason to live sustainably, what could be?’ 34 March 2009 ECOLOGIST 32-35 Mar Hope - ER 34 to mistrust authorities, such contradictions justifiably elicit mistrust. Environmental leaders need to employ motivators for living sustainably that do not appear contradictory, and that do not require trust, but that are self-evident. Mere hope will simply not do. When hope is controversial – as it has been since Pandora’s jar – the environmental leader’s most effective strategy is to provide a self-evident motivation. But if hope for averting environmental disaster isn’t the right reason to live sustainably, what could be? Vicious or virtuous? If ‘not being hopeful’ really meant being in despair, then giving up hope may be unacceptable, if not incomprehensible. This ontology gets it all wrong, however. Consider again athletes who really have no chance of winning a competition. Do they all really hope to win? Probably not. Might not some athletes – those with realistic expectations and honour – compete simply because the virtue and rightness of the activity (competing) is more important than any particular outcome (winning or losing) – which is not entirely within the control of the athlete? The athlete is not hopeful, nor is she in despair. She competes simply because she believes it is virtuous to compete. The assumption that despair is the necessary and unacceptable B-side to hope, www.theecologist.org 5/2/09 18:22:21 and that the hope/despair dichotomy captures the sum of all ethical motivators, shows a preoccupation with the consequence of our actions over and above the inherent virtue of our actions. It also suggests a preoccupation with judging the rightness of an uncontrolled circumstance rather than judging the rightness of one’s own actions. Such preoccupations diminish the value and role of ethics in environmental problemsolving because there is something futile and morally vacuous about judging the rightness of the circumstances in which others involuntarily find themselves. In contrast, judging the rightness of one’s own actions, given one’s circumstance, is a wholly ethical activity, and perhaps the whole of ethical activity. The 19th and 20th centuries were like no other in human history, not so much because of advances in technology, the advent of industrialisation or global environmental crises and warfare, but because of the dominating influence of an odd form of ethics. Up until that, a phenomenon known as the Enlightenment Virtue Ethics, and healthy ecosystems, dominated the western world. Since the mid 19th century, however, Utilitarianism has permeated nearly every aspect of our lives – why we pick the jobs we do, our laws and policies, and even what counts as having lived a good life. Utilitarianism holds that moral actions are those whose future consequences are good, inasmuch as they produce the most utility, happiness or pleasure for the most people. So we’ve built a society fixated on the future, perpetually risking all the attendant problems of justifying means by their ends, and forever flirting with endorsing the hedonistic instincts of the masses. Even though the ethical tyro knows that morality depends on motivations, Utilitarianism, oddly, has not the least interest in motivation. Utilitarianism’s fixation with the future requires a means for judging the future; in this way hope, despair and Utilitarianism are entwined. Our preoccupation with the future at the expense of concern for the present is a hallmark distinguishing the Modern West from non-Western cultures and even from its own moral history. Twenty-three hundred years ago Aristotle worked out many details of what we now call Virtue Ethics, which holds that ethical people are those who appropriately manifest virtues such as respect, humility, empathy, sharing and caring. We usually think hope is a salve; the Greeks thought hope was a scourge. The Greeks had a proclivity for judging the virtue of present actions, and hence considered hope just another way of being preoccupied with the future and thus a distraction from morality. www.theecologist.org 32-35 Mar Hope - ER 35 We, however, have a proclivity for judging the utility of future outcomes, and thus we sanctify hope. From this sanctification we even develop odd beliefs about how hope can affect the future. Doing the right thing The notion that being hopeful is not unconditionally virtuous, and can, at times be delusional is oddly juxtaposed with a Christian view of hope that dominates the Western mindset: the more hopeless the circumstance, the more unconditionally virtuous it is to be hopeful. But Christian hope has nothing to do with the welfare of life on Earth; it refers to ‘hope in eternal life in heaven’. If we find it difficult to believe that hope is sometimes vicious, it may be because the modern secularist has inherited, with remarkable transformation, the Christian view of hope. Like a moth to the flame, the modern secularist is drawn to unconditional hope. However, the environmental secularist’s hope is earthbound and concerns a future over which they have little control. It is difficult to conceive of a more tragic transfiguration of the Christian conception of hope. Instead of hope we need to provide young people with reasons to live sustainably that are rational and effective. We need to equate sustainable living, not so much with hope for a better future, but with basic virtues, such as sharing and caring, which we already recognise as good in and of themselves, and not because of their measured consequences. Living by such virtues is a fundamentally right way to live – even if nobody else does and even if it might not avert environmental disaster (see table, opposite page). Relating sustainable living to virtues such as caring and sharing has other important benefits. First, it can motivate sustainable living in people who do not even believe we are on the verge of environmental disaster. One only needs to understand that a less disparate distribution of wealth requires more sharing (rather than more extraction). Second, it clarifies the connection between environmental and social problems – a connection that many people fail to grasp. There is a desperate need for environmental educators, writers, journalists and other leaders to work these ideas into their efforts. We need to lift up ‘Instead of hope we need to provide young people with reasons that are rational and effective’ There is one point where the narrative in An Inconvenient Truth touches on this moral truth. Gore tells us that after his sister Nancy died of lung cancer, his father stopped farming tobacco not because he hoped that his actions would have some impact on the future, but because it was the right, or the virtuous, thing to do. Evidence about future effectiveness was an irrelevant, even inappropriate, consideration. So, it is ironic that Gore boldly and correctly insists that global warming is a moral issue, yet his reasons for why we should live sustainably are, in the end, morally vacuous: if you live sustainably, and others do the same, there is hope – and one should never give up hope – that we will avert environmental disaster. Inspire by example This is no neo-Stoic attempt to abolish emotion. Emotions are essential for a healthy ethic. Consider, for example, sadness. Environmental abuse is a sad circumstance. If you love the environment, to respond with sadness is virtuous and can inspire care. examples of sustainable living motivated by virtue more than by a dubious belief that such actions will avert environmental disaster. Without such examples, one is justified – sadly so – in being hopeless about one’s future as a virtuous person. If they do, there may be legitimate reason to hope for a better relationship between society and nature, and hope to avert environmental disaster. MichaelPNelsonisanassociateprofessor ofenvironmentalethicsatMichigan StateUniversityandco-authorof American Indian Environmental Ethics: An Ojibwa Case Study.JohnAVucetichis anassistantprofessorofanimalecology atMichiganTechnologicalUniversityand co-leadsresearchonthewolvesand mooseofIsleRoyale,aremoteislandin LakeSuperior.NelsonandVucetichcofoundedandco-directTheConservation EthicsGroup,anenvironmentalethics consultancygroup.See:www. conservationethics.org ECOLOGISTMarch 2009 35 5/2/09 18:22:26