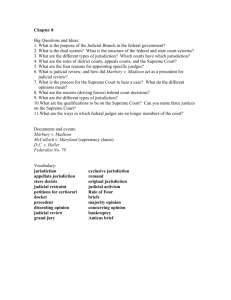

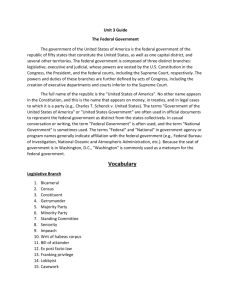

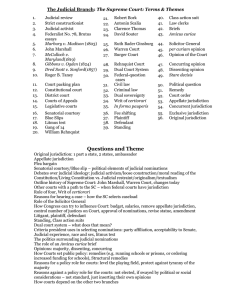

DAM FEDERAL JURISDICTIONI

advertisement