B C U A

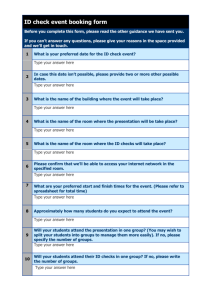

advertisement