Document 12860096

advertisement

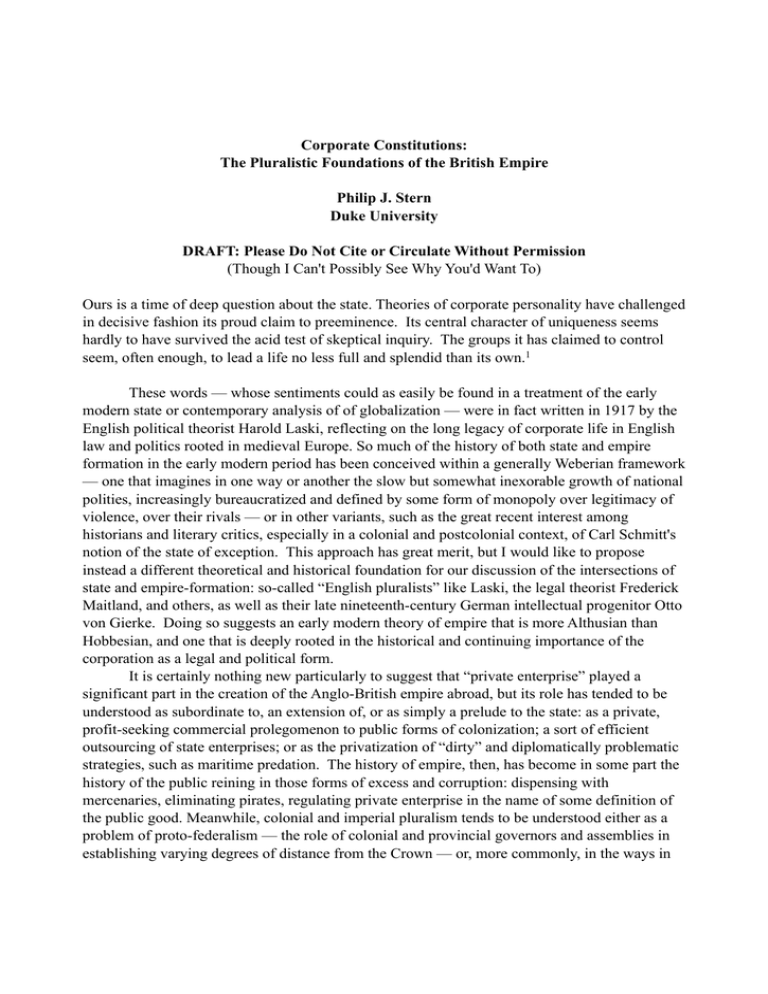

Corporate Constitutions: The Pluralistic Foundations of the British Empire Philip J. Stern Duke University DRAFT: Please Do Not Cite or Circulate Without Permission (Though I Can't Possibly See Why You'd Want To) Ours is a time of deep question about the state. Theories of corporate personality have challenged in decisive fashion its proud claim to preeminence. Its central character of uniqueness seems hardly to have survived the acid test of skeptical inquiry. The groups it has claimed to control seem, often enough, to lead a life no less full and splendid than its own.1 These words — whose sentiments could as easily be found in a treatment of the early modern state or contemporary analysis of of globalization — were in fact written in 1917 by the English political theorist Harold Laski, reflecting on the long legacy of corporate life in English law and politics rooted in medieval Europe. So much of the history of both state and empire formation in the early modern period has been conceived within a generally Weberian framework — one that imagines in one way or another the slow but somewhat inexorable growth of national polities, increasingly bureaucratized and defined by some form of monopoly over legitimacy of violence, over their rivals — or in other variants, such as the great recent interest among historians and literary critics, especially in a colonial and postcolonial context, of Carl Schmitt's notion of the state of exception. This approach has great merit, but I would like to propose instead a different theoretical and historical foundation for our discussion of the intersections of state and empire-formation: so-called “English pluralists” like Laski, the legal theorist Frederick Maitland, and others, as well as their late nineteenth-century German intellectual progenitor Otto von Gierke. Doing so suggests an early modern theory of empire that is more Althusian than Hobbesian, and one that is deeply rooted in the historical and continuing importance of the corporation as a legal and political form. It is certainly nothing new particularly to suggest that “private enterprise” played a significant part in the creation of the Anglo-British empire abroad, but its role has tended to be understood as subordinate to, an extension of, or as simply a prelude to the state: as a private, profit-seeking commercial prolegomenon to public forms of colonization; a sort of efficient outsourcing of state enterprises; or as the privatization of “dirty” and diplomatically problematic strategies, such as maritime predation. The history of empire, then, has become in some part the history of the public reining in those forms of excess and corruption: dispensing with mercenaries, eliminating pirates, regulating private enterprise in the name of some definition of the public good. Meanwhile, colonial and imperial pluralism tends to be understood either as a problem of proto-federalism — the role of colonial and provincial governors and assemblies in establishing varying degrees of distance from the Crown — or, more commonly, in the ways in "2 which European legal regimes co-existed with other European or indigenous forms of governance. Of the three basic forms of colonial rule that the eighteenth-century jurist William Blackstone identified in English colonial rule — Crown or state “provinces,” proprietary rule, and “charter,” or corporate rule — corporations seemed to have generated the greatest claims to autonomy.2 Colonies ruled by directly from state were exceptional. More common of course were proprietorships. Essentially modeled on rooted in seigniorial palatinates and bishoprics in England — Durham was often the model — these charters tended to allocate lands in capite, that is directly held of the monarch, as in a manor; they offered a vast amount of discretionary power, particularly to administer justice and alienate land, but also theoretically placed great burdens upon its holders, and were far more susceptible to royal intervention and even revocation. Corporations, on other hand, could not be considered vice-regents nor, in a technical sense, manorial lords. Their colonial holdings tended to be issued neither in capite nor rooted in a particular manor. While both proprietary and corporate grants were grants in socage (that is, requiring no feudal service, which was, in any event, abolished across the board after the 1650s); but the fact that corporate patents were more like freehold grants than feudal tenures meant they could not be summarily recalled, require service or obligation beyond the payment of rent, or behold the patent holder to the immediate supervision of the Crown. In short, the grant of free tenure actually implied a significant latitude of rights with respect to self-government, and confused rather than clarified the division of rights of government amongst Crown, patentee, and settler.3 These distinctions, of course, were legal ideal types. First of all, corporations came themselves in varying shapes and sizes, from large commercial bodies to fairly small local municipalities. Moreover , in practice, many settlement efforts offered what appeared to be a fusion of both the palatine and corporate traditions. In 1627, the Council for New England granted land to the voluntary organization calling itself the New England Company, which promptly sought incorporation as the Massachusetts Bay Company, along the lines of the earlier Virginia Company though with a number of features that resembled the more recent proprietary ventures’ emphasis on governing over territory, settlers, and religion. In 1639, Gorges sought a form of palatine jurisdiction in Maine, but under the rubric of his corporate company.4 The admission of so many new settlers to the freedom of the Massachusetts colony prompted its government to restrict their franchise from direct to representative government; the system of deputies that ensued was premised on Governor John Winthrop’s insistence that the government was now “in the nature of a parliament” rather than a mayor and corporate council.5 New York city’s corporation was hybrid in its very origins as a Dutch colony, and the New York colony, as Daniel Hulsebosch has put it, represented a mélange of forms: “part proprietary, part corporation, part country, and part replica of the whole of England.”6 The charter for Rhode Island was, in the words of another historian, “a cross between the small municipalities that dotted the English countryside and a business company.”7 New Haven organized its early government “in like manner the companyes of London chuse the liveries by whom the publique magistrates are chosen.” Carolina and Georgia were proprietorships, but, as they were vested in consortia rather than individual proprietors also shared critical commonalities with corporations. And the distinctly “business” corporation of the East India Company obtained royal charters in "3 the 1660s for colonies at Bombay and St. Helena, which mixed corporate and proprietorial formulae, and clearly implied expectations of manorial rights vested in the Company as “absolute Lords and Proprietors.”8 Thus, one finds the governor and council at St. Helena claiming the right not only to govern St. Helena but alienating land under whatever sorts of tenure it saw fit and justifying administering justice and issuing fines for “all cases of trespass, misbehaviour, breach of the peace, or high misdemeanor,” as similar to “his Majesty in our courts at Westminster and at all Court Leets to the respective Lords of the manner.”9 Corporations thus by their very nature engendered a pluralistic legal and political system, in both senses in which that term is frequently used: i.e., as overlapping institutional and jurisdictional forms, and as hybrid forms of law in themselves. Some ardent defenders of colonial autonomy, like Yale's own Jeremiah Dummer, even argued that corporate colonies served as a necessary check on the arbitrary rule of Crown governors and officials.10 Corporations certainly regulated trade and governed markets, both at home and abroad.11 The consultative structure of their governance and the hybrid nature of their legal and political foundations also made corporations ever more likely to tend ideologically towards a sort of normative pluralism, in an amalgam of legal traditions, theories, and precedent: republican, feudal, common, civil, natural, martial, and despotic forms of law, including the extremely common notion of “equity,” equally important to the lex mercatoria and various forms of colonial governance, not to mention the ability to absorb and accommodate indigenous law and custom as well as the accumulated customs of a colony itself.12 By turning to the corporation as one of several fundamental groundings for the colonial constitution, I propose to explore a different way of thinking about the categories into which we tend to divide colonial life: maritime and territorial; Atlantic and Asia; settlement and rule. It is also a suggestion for rethinking our very understanding of the boundaries of "private" enterprise: that that which we have tended to consign as private — such as colonial companies — were really conceived of in quite public and political terms, akin and often outgrowths of other more easily recognizably "public" corporate forms. There was thus a continuum of corporate life at home and abroad that in turn renders varieties of corporations — companies, cities, colonies — in a single if multifaceted frame, if for no other reason than the fact that the English state routinely assaulted the autonomy of all three, often using the very same legal instruments and political arguments for doing so. A second, though related point, that arises from this proposition is that corporations served as the foundation for a cacophony of intra-imperial layers of governance and conflicts that in turn underscored the European expansion overseas; as such, though studies of legal pluralism and empires tend to focus more on the intersections of various European and indigenous forms of law and dispute resolution, companies in conjunction with other forms of corporate life reveal the complex plurality of colonial governance, even within imperial frameworks that are nominally hierarchical or singular in their constitutional foundations. My focus is largely on the British, but of course the corporate life of other European empires was equally if not more robust in its various forms. By looking at the ways in which corporations of various stripes underwrote the financial, political, and even cultural foundations for empire, we can significantly complicate the different categories to which we consign different forms of corporations while reinforcing our understanding of the way empire itself "4 worked: as a mélange of bodies politic, that fixed in the overseas world the layered and overlapping forms of bodies politic that made for European civil society. Yet, while pluralism provided the flexibility and diversity necessary for managing such an empire, it also produced jurisdictional tension and fissure, between corporations and the state as well as within and amongst corporations themselves. It also sheds new light, by taking a long historical view, on the predominant role of the figure of the corporation in shaping debates over the future of colonialism in the late eighteenth century, in both the Atlantic and Asia. Doing this, in turn, situates the various ideas about early modern and modern empire within the ongoing negotiation between the pluralism embedded in corporate life and the centralism exhibited by the increasing emergence of more singular notions of state and empire, one which in many ways has yet to be resolved. 1! Harold Laski, “Early History of the Corporation in England,” Harvard Law Review (1917), 561. 2 Though, Herbert Osgood argued in a series of articles in 1896 and 1897 that Blackstone’s taxonomy was flawed, and proposed instead only two forms: provincial and corporate. See Herbert L. Osgood, “The Corporation as a Form of Colonial Government, I” Political Science Quarterly 11, 2 (1896), 259-77, as well as parts II (issue 3, pp. 502-33) and III (issue 4, pp. 694-715). 3 Christopher Tomlins, Freedom Bound: Law, Labor, and Civic Identity in Colonizing English America, 1550-1865 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 161n87, 166-68, 170-71; Craig Yirush, Settlers, Liberty, and Empire: The Roots of Early American Political Theory, 1675-1775 (Cambridge, 2011), 52 n5. On the proprietary colonies and the palatinate model, see Vicki Hsueh, Hybrid Constitutions: Challenging Legacies, of Law, Privilege, and Culture in Colonial America (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010). See also B.H. McPherson, "Revisiting the Manor of East Greenwich," The American Journal of Legal History 42 (1998); Michael Craton, "Property and propriety. Land tenure and slave property in the creation of a British West Indian plantocracy, 1612-1740," in Susan Staves and John Brewer, eds., Early modern Conceptions of Property (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 499; Edward Keene, Beyond the Anarchical Society: Grotius, Colonialism and Order in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 62-68. 4! Tomlins, Freedom Bound, 173-75. 5! Osgood, “The Corporation as a Form of Colonial Government,” 515. 6! Daniel Hulsebosch, Constituting Empire: New York and the Transformation of Constitutionalism in the Atlantic World, 1664-1830 (UNC, 2008), 43, 52-55, 87-90. 7! Edward M. Cook, Jr., “Enjoying and Defending Charter Privileges: Corporate Status and Political Culture in Eighteenth Century Rhode Island,” in Robert Olwell and Alan Tully, eds., Cultures and Identities in Colonial British America (JHU, 2006), 247, 258. 8! Philip J. Stern, The Company-State: Corporate Sovereignty and the Early Modern Foundations of the British Empire in India (OUP, 2011), 24-25. 9! London to Bombay, 25 Aug 1686, British Library, India Office Records, E/3/91 f. 84. 10 11 Jeremiah Dummer, A Defence of the New-England Charters (1721), 35. 38-39. Thomas Nachbar, “Monopoly, Mercantilism, and the Politics of Regulation,” Virginia Law Review 91, 6 (2005), 1320. 12 Hseuh, Hybrid Constititutions, 64-65; Tomlins, Freedom Bound, 188 "5