Financial Support for Families with Children: Mike Brewer

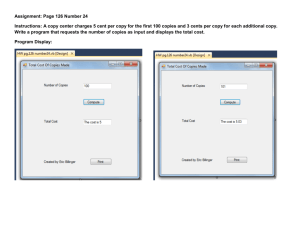

advertisement