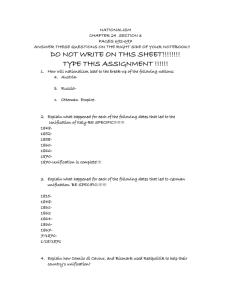

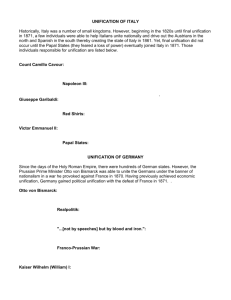

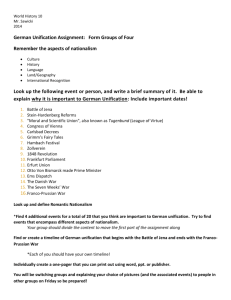

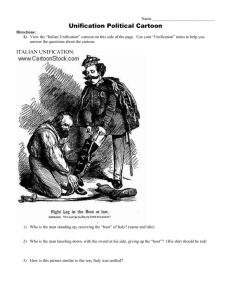

Redacted for privacy

advertisement