auitted ta partial fulffl lent of tar tbs dsgree of

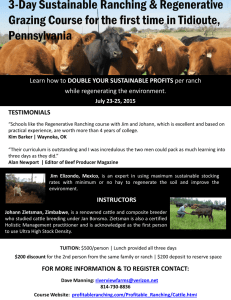

advertisement