Death and Texas: The Unevolved

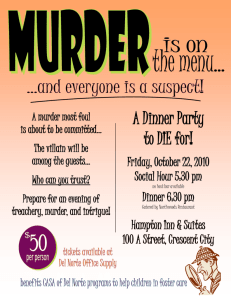

advertisement